Dianna Snape speaks to Mark Strizic about life, photography and his recent exhibition.

On the Public Library Steps, 1956.

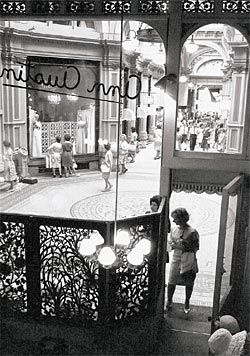

Queens Arcade – 5, 1957.

Near the Intersection of Victoria and Exhibition Streets, 1956.

Block Arcade – 1, 1964.

Mark Strizic’s Melbourne Mid Century exhibition is a collection of his silver gelatin prints and large-scale digitized fabric banners. It presents an evocative assortment of images of Melbourne and its inhabitants taken between 1954 and 1969, captured with sensitivity to his subjects and their environment.

At 78, Mark is a talented photographic artist whose diverse career has spanned almost fifty years, challenging him to embrace some of photography’s most significant technological advances. From the black-and-white era to the introduction of colour film and today’s digital revolution, Mark has incorporated these new tools into his work and has continued to expand his craft.

His fascination with collecting Melbourne images began decades ago and was motivated by a book of images his father, a professor of architecture in Croatia, took of Zagreb. “Never being a photographer, he took brilliant photographs. My father was an architect and a professor of architecture. He was an immensely talented man who spoke several languages quite fluently. He was extremely well read; he played music and knew more about music than me.”

Mark was born in Berlin in 1928. His family fled Germany in 1934 as soon as Hitler became Chancellor. They settled in Zagreb, Croatia, where Mark studied geology for two years before studying physics. “I wanted to solve these problems that Einstein couldn’t solve – which was an idiotic idea, like all young people’s ideas. I couldn’t add up, let alone solve, any complicated problems, but if there was a philosophical idea behind it, then I was interested. In logic and in philosophy, and in thinking about right and wrong, in seeing whether the law is bad or good. So logic and thinking, philosophy was my forte.”

Mark immigrated to Melbourne in 1950 and it was here that his curiosity about photography began. “When my father saw my first photographs he said forget about physics, you are a photographer. Eventually I was so busy with photography I had no time to study.”

The social variance between Melbourne and Europe is reflected in some of the scenes and moments captured in the exhibition. “The man sitting on the library steps – it is so incongruous in terms of European feeling. Europeans have a great sense of respect for institutions, whether it be a government or a public library or an opera house. The first thing they did after bombing was repair the opera house. They didn’t worry about the houses or streets; it was the opera house. I wouldn’t dare do this in Europe, sit on the steps – maybe now, but not in those days. Australia is so rich, yet the public spaces are so poor. Where is the opera house? There isn’t any opera house. Zagreb’s opera house is an enormous structure, it is in the middle of a huge space and there is little space in Europe.”

Mark attributes this difference to the fact that the intellectual aspects of human endeavour were highly appreciated in Europe, rather than the physical. “All the books I read as a schoolboy in Croatia were from writers whose theme was to raise yourself out of your level of society, for a peasant to become an intellectual. That was the main aspect of struggle in Europe. Here they couldn’t care less whether you are a plumber or a professor of physics.”

When I view these eloquent moments captured with such precise timing, I am curious as to the photographer’s experience, particularly today when our visual palette is overloaded with manipulated and staged imagery. Mark looks up and responds to two images in front of us. “I wasn’t looking at this lady waiting for her to scratch her nose; the only thing I was worried about was verticality, parallel lines – because I wouldn’t accept that. And there is a hobo walking up Exhibition Street – this is one of those moments when I said to myself, that’s got to be done because that is nowhere but here, an old man carrying his entire possessions on his shoulders and he is going to the soup kitchen.”

Mark’s first job as a photographer was through Len French (“Lenny Boy we used to call him”), the artist who designed the ceiling of the great hall in the National Gallery of Victoria. “He was exhibitions officer at the National Gallery and he got me a job producing photographs that reflect the themes of the famous painters exhibiting at the National Gallery.”

Renowned in architectural circles for his collaboration with Robin Boyd on the book Living in Australia, Mark is equally recognized for his portraits, commercial and advertising assignments and large-scale conceptual murals. His images are part of the collections of the National Gallery of Australia, the National Gallery of Victoria and the Monash Gallery of Art.

Mark’s career has blurred the great delineation between the commercial photographer and the art photographer.

“Architectural photography, that’s an interesting thing. People are labelling me as an architectural photographer. Time and time again, I have said that curators are trying to categorize you – oh, he’s a Melbourne photographer, or he’s an architectural photographer or he only photographs advertising or so on and so forth, forgetting that I’ve done the lot. In other words, I can’t see the limit. There’s not enough intellectual scope in any one discipline of photography to keep your interest. You can photograph a car as well as you can photograph a lady and that’s not the end of it. The end of it is when you can control it by your own photochemical machination, control the colour and the form like you do now on the computer. I find that computers are a great, great drawback to the quality of photography because most of the people who handle computer imaging don’t know about composition and don’t know about the empathy of the audience, the viewer. They haven’t got the feeling – how will the viewer view this image? They go so quickly through the images that it becomes meaningless.

“A famous designer once said to me, how do you photograph this ugliness, this rubbish? Pointing to some cutlery or crockery, whatever I had to do for an advertisement. I said, it is not my job to make aesthetic judgments, my job is to do the best I can with the camera to show an aspect of the object in such a way that it will attract interest, irrespective of its aesthetic.

“I was once advised that I was suffering from anxiety. I’ve spent my life anxious about whether there will be sun on the building at 6.00 o’clock in the morning, because later on you can’t photograph it. Do I go 300 kilometres or do I stay home? Do I do this job or do I do that job? Do I buy this equipment or do I pay this bill? So it is no wonder that I am anxious.” No matter how Mark Strizic’s legacy is categorized, I smile at this comment – these are the daily anxieties of an architectural photographer.

The Melbourne Mid Century images were selected by Dianna Gold of Gallery 101, 101 Collins Street, Melbourne. The exhibition ran from 14 March until 1 April. A smaller collection of the works will be displayed in the foyer of 101 Collins Street in the coming months.

Images from Mark Strizic’s Melbourne Mid Century exhibition.