For 30 years, Fabio Ongarato and Ronnen Goren have helped to shape the identities of some of the country’s most iconic institutions. From Sydney’s Phoenix Gallery, the Powerhouse Museum, Melbourne’s Ian Potter Gallery to the Jackalope Hotel, Studio Ongarato has challenged the conventions of branding, wayfinding and placemaking with striking and enduring concepts that help determine the user experience.

“In the early days, we were very heavily involved in fashion, art direction, brands and corporate work. But really, as a practice today, we’re much more concerned with how brands and environments share synergistic values,” says Ronnen Goren.

Left, Ronnen Goren, right, Fabio Ongarato.

Image: Gavin Green

Goren was studying architecture at RMIT. He was curating an exhibition of Australia’s post-war Jewish émigré architects when he met graphic designer Fabio Ongarato. The pair quickly found they shared a common love of designers Charles and Ray Eames, and from their shared interests, the seeds for the studio began to germinate. The pair has now successfully established a cultural niche for their practice that transcends industries and disciplines.

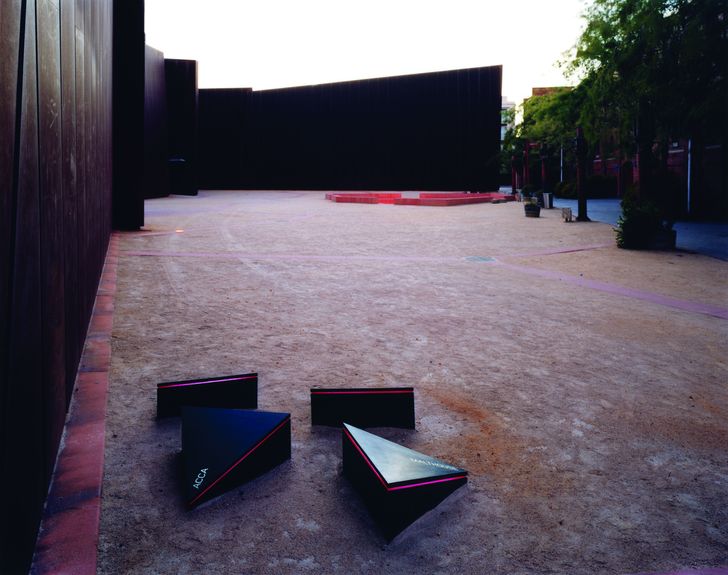

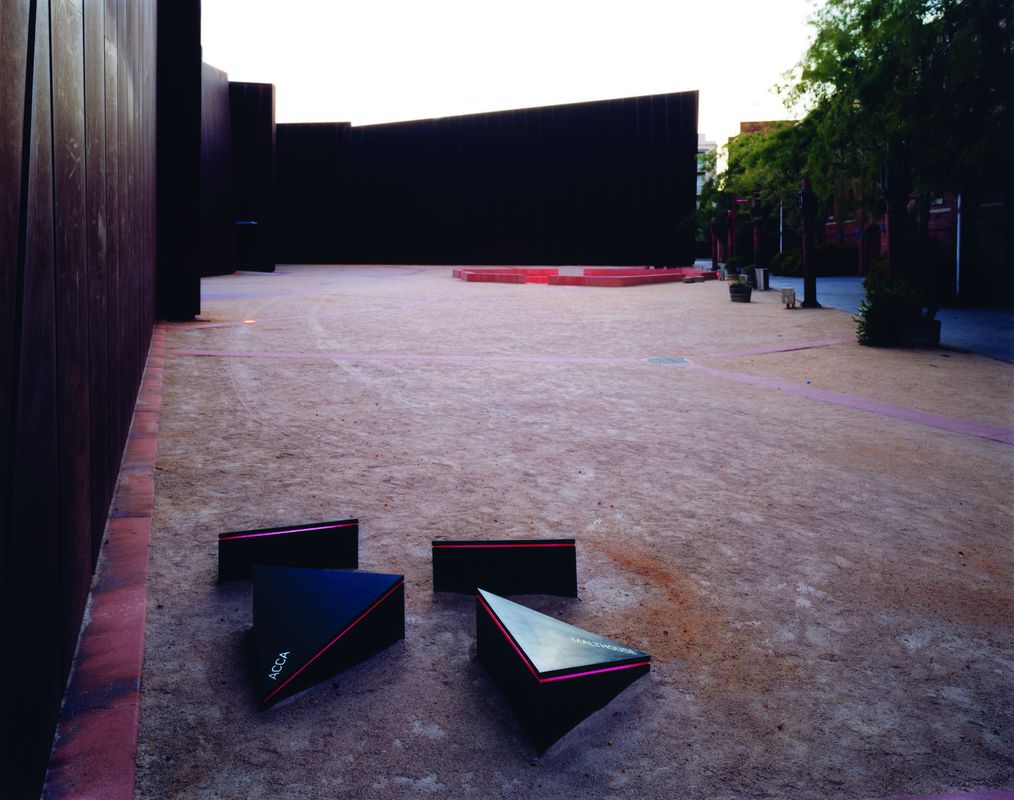

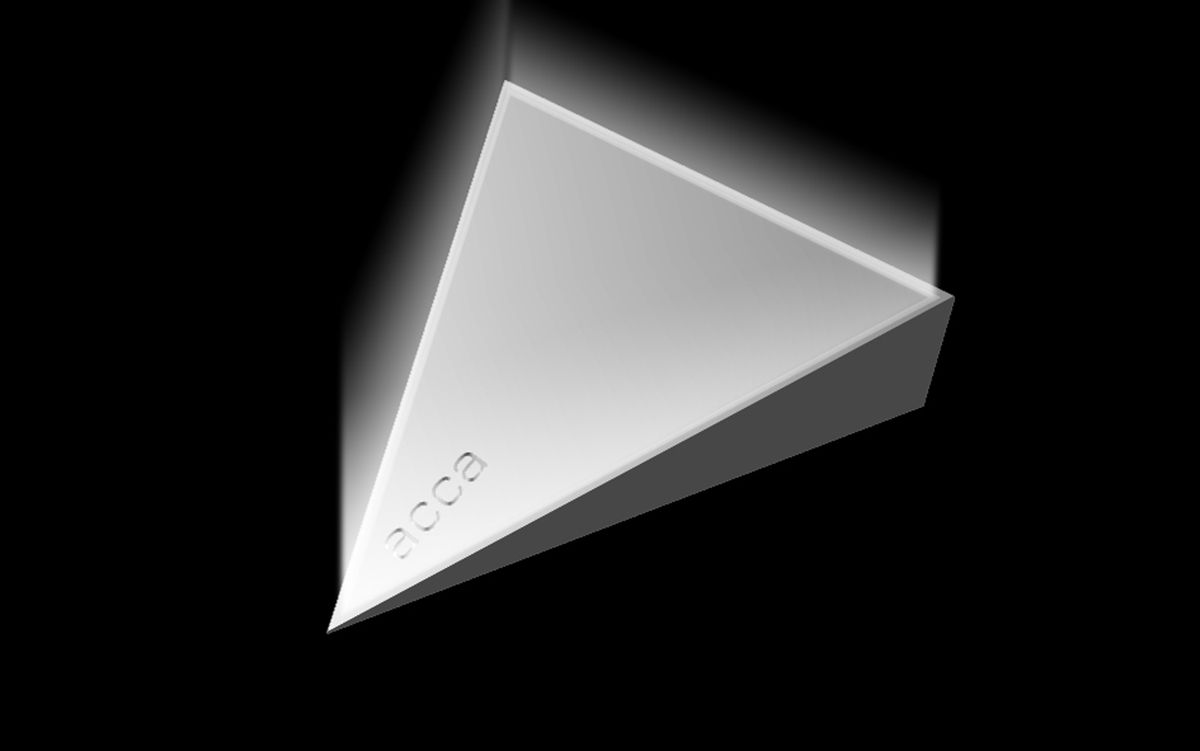

Studio Ongarato’s first foray in wayfinding was for the Australian Centre for Contemporary Art (ACCA), completed in 2002 and designed by Wood Marsh. “We were fortunate, then, being like the new kids on the block and receiving mentorship from luminaries, or an older generation of designers that took us under their wing,” says Goren.

“With ACCA, there was this idea to create what Roger Wood and Randall Marsh called an ‘alien landscape’: it was an amazing structure emerging from earth, like a scene from Dune or out of a de Chirico painting,” says Ongarato. “We created the ACCA identity and the associated type face as it is today. The idea for our signage was to mimic the building and make it feel like it was rising from the ground.”

Wayfinding for Australian Centre for Contemporary Art (ACCA), 2002.

Image: Supplied

Studio Ongarato devised a futuristic visual language with triangular forms rising from the ground, the angle of which would indicate the direction you needed to go.

“We didn’t really have the science or the know-how of the mechanics, because signing is very much two part: one is the creative, of course, but the second part is the theory of how people navigate through place in space,” Ongarato continues.

“But it did leave us with this notion of how to create a conceptual, tactile experience guided by a strong conceptual thread, which we still do today. It’s about a deeper understanding of architectural intent, and how to recreate an interesting dynamic, whether it is seamless and integrated with the architecture or creates a certain juxtaposition to create a certain identity for place.”

Studio Ongarato’s most recent wayfinding project was another civic institution, the Western Australian Museum Boola Bardip (WAM).

“The complexity of the task was far greater and we had 20 more years of developed skill to tackle the problem,” says Goren. “The intelligence and the rigor, plus a multidisciplinary approach, has given us more permission to work more closely with architects and interior designers conceptually.”

Western Australian Museum, Boola Bardip.

Image: Peter Bennetts

For the concept, Goren and Ongarato were interested in the way that museums collect artefacts and are, in their own right, an assemblage of history. They resorted to signs that were a composite of different typologies – trifold flaps to digital screens – that encouraged the active consumption of knowledge, “facilitated by a sign system that employs a self-directed approach through variable technologies,” says Ongarato.

As a popular visitors destination, Studio Ongarato wanted to embed a degree of universality on the visual language for the museum. “The requisite for inclusion is much broader,” said Goren. “We had elements that were non-language denominated (signs and symbols); we had elements that were in English; and elements that acknowledged Country,” says Goren.

While their rigour and know-how may have evolved, Goren and Ongarato maintain that they still approach every project with fresh eyes and a renewed sense of curiosity. “Risk and experimentation is still very much part of our process,” says Ongarato. “Studios, after they’re established, can become a factory, and that’s something we never wanted to be.”

“I’ve always followed the mantra that you’re only ever as good as your last job,” says Goren. “That way you can’t rest on the laurels of your past success, and you have to bring a fresh slate and open mind to every project.”