Kirsha Kaechele is a conceptual artist, Museum of Old and New Art (MONA) curator, and advocate for sustainable building design. Born in California, raised in Guam, Micronesia, and now residing in Tasmania, Kaechele defies categorisation as much as her work, with her canvases including the derelict streets left in the wake of Hurricane Katrina; the metal-polluted river of Derwent; and a dinner spread held on the world’s largest glockenspiel.

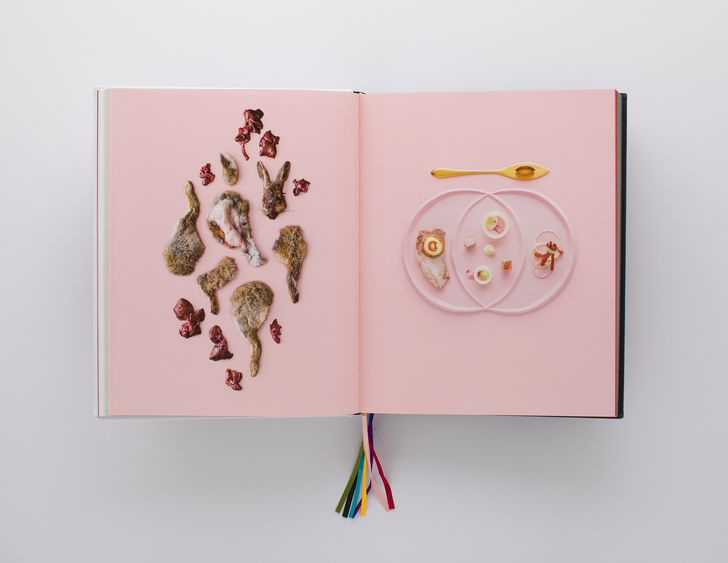

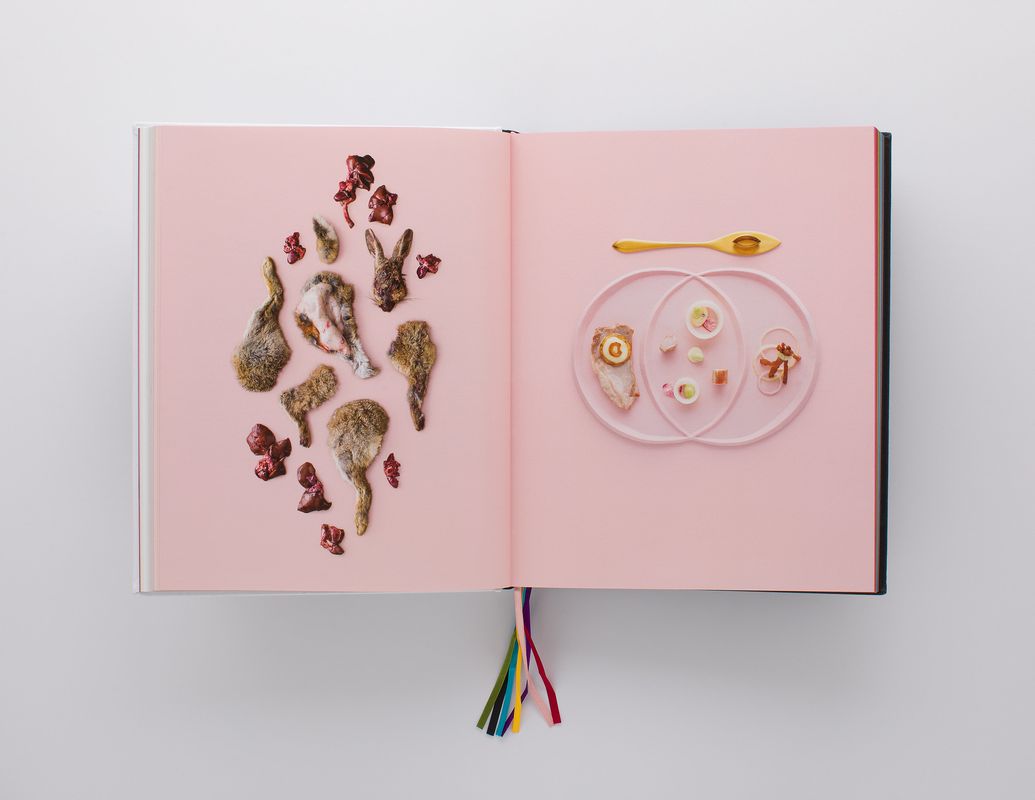

In 2015, Kaechele staged the largest gun buyback in New Orleans history in a conceptual work for the Biennial, Prospect.3, and her 2019 exhibition Eat the Problem involved the publication of a cookbook with recipes made from invasive species, from cats to “crispy skinned” cane toads.

Ahead of Architecture Media’s The Architecture Symposium in Hobart, Kaechele speaks with ArchitectureAU about the ingredients for an artful life, from psychedelics to sewage.

AAU: The theme of the symposium is “Ideas from the Fringe”. What is your relationship with tradition and convention – have you always felt the need to flout or subvert it? And if so, from where does this rebellious streak originate?

Kirsha Kaechele: From about sixth grade onwards, I’ve exercised a pretty unconventional perspective. It wasn’t hard, as I was at Catholic school in Guam where I was the only white girl, so there was never any hope of fitting in. Maybe this pushed me to embrace my difference and repackage it as a gift. Or maybe I would have turned out strange anyway, as my parents had shirked the status-quo well before my birth. I was a child of the convention shake-off of the 60s and 70s. My father left the think-tank at Rand Corporation to join an LSD therapy group and become a Rolfer [an alternative medicine practitioner concerned with the body’s energy field]. And my mum is, to this day, a complete free spirit: a wild minded, sex-bomb painter. All the characters I play are based on her.

Big Mamas, Snake’s Belly, Elena Stonaker in Eat the Problem, MONA.

Image: Jesse Hunniford

AAU: You were born in California, raised in Guam, and now reside in Tasmania (and everywhere else in between). How has place and its transience had an impact on your work?

KK: The basis of all my thinking, and the wellspring of my work, is the fact that everything is impermanent—this too shall pass, we all die. I’m looking for something transcendent, for a process of transformation that will reveal not just those truths, but the whole “Ah-Ha” suite.

I tried to find answers in place, but overall, it’s inconsequential where you are. Of course, you can’t beat the Mediterranean, but that aside, one can make great work, and therefore find meaning, anywhere. I’m only in Tasmania because I met a cute guy from there. But, the paradox is, work is what connects us to place, and in art and in architecture, site-specificity is everything.

So as a young traveller, when I stopped hitting my head against my own wanderlust, it became clear that I had to create. For long as I’m creating things, I’d like to make things that are transcendent and beautiful, that bring us back to that place of knowing – that this is impermanent – and that remind us of the irrelevance of where we are, yet the perfection of here.

“Eat the Problem”: a recipe book designed to tackle the issue of invasive species.

Image: Jesse Hunniford

AAU: Where some art might be rooted in the celestial, much of yours has a very tangible impact on the real world. How do you respond to critics who say art is inessential or a luxury? And how do you think art can form part of the ethical, civic and moral fabric of a society?

KK: My science-nerd husband would say art is essential because it is inextricably entwined with evolution: it’s a tool we use to procreate. As a human, and therefore a mere instrument of the genetic forward march, I have no choice but to make art. I’m compelled. That said, I can sympathise with the critics because it certainly looks like a luxury. I even experience it as one.

But art is everywhere. Why is that? Even the person who does not have the means, like I do, makes art. Against adversity, it seeps through, like weeds in the cracks of a sidewalk.

Some cultures bring art into everything—these are beautiful places in the world to visit. Some don’t even have words for “art” because it is so foundational to how they live.

Artfulness makes a good society, so we need to bring it into ours by investing in children, teaching the arts in schools, and introducing artfulness into civic experience through architecture and design. People should live in and around great art and touch it every day. There should be no ugly objects. (Uh oh, I am revealing my aesthetic fascism!)

AAU: You are a conceptual artist but also an aesthete. Do you put more emphasis on the concepts you present in your works, or their appearance and execution?

KK: It is a moving dial, but only based on how strong or weak my concept is, because the work had better be beautiful. So, yes, the aesthetics are kind of an inescapable given – a constraint, even. I respect artists who can just get an idea across, but I’m compulsive about aesthetics. This can seem like a flaw, but then I look at people who are even more obsessed and I admire them, like John Wardle. He makes his ceramics fit perfectly in the negative spaces of his tables, which fit perfectly in his houses. He is not normal. But thank God!

24 Carrot Gardens, school kitchen garden project.

Image: Jesse Hunniford

AAU: A lot of your work engages with aspects of the built environment and explores issues like the tussle between nature and human interventions. What role does architecture serve in your life and your work?

KK: There is something about letting things unfold and responding a bit at a time that I love. I’ve engaged four architects – Edition Office, Room 11, Herzog and De Meuron, and Assemble – on Material Institute, my school in New Orleans, and still, it is a weird hodgepodge of half broken buildings. I have a rebellious head of the 24 Carrot Garden Project who insists on cultivating traditional food gardens in the middle of his sculptures. It is a big mess, but for some reason I can’t impose perfection on it. The outcome is so interesting. I like to shock my atheist friends by describing the phenomenon as “God is the Curator”. But maybe I’m just a soft-cock curator that lets life run all over me. Still, in the middle of all the madness I manage to create moments of beauty.

AAU: Your art often agitates, confounds or shocks. Do you think it is essential that art moves viewers out of a state of complacency?

KK: I don’t think it is essential at all. I think it is very immature and déclassé, but I can’t help doing it. I’m actually tuned to be a minimalist, but I don’t know what happened: everything I hate I become.

Kirsha Kaechele in an artist and curator at MONA, Hobart.

Image: Jesse Hunniford

AAU: “Kirsha Kaechele” the artist seems to attract just as much attention as the art. Do you think you are ultimately inseparable from your art (contrary to Roland Barthes’s thesis that the work is not the author)? And do you find that your self-portrayal is perhaps one of your most enduring projects?

KK: I suspect I am inseparable from my art. But sometimes I feel completely irrelevant to it, just a vessel or a witness. This is my favourite experience in art.

Alfredo Jarr said, “Why don’t you just proclaim that your entire life is art?” And I said, “Well, I don’t feel it is.” Sometimes I am just a housewife or an interior designer, or even, an architect.

While all my projects are artful, some, like 24 Carrot, don’t feel like art; they feel essential and far more important, but not nearly as fun. It’s a little ambitious to say Life is Art (the name of my first foundation). It’s more like, Life can be Art. But…I’m aspirational.

AAU: What (or who) has been the greatest influence on your work to date?

KK: There are many. All the great minimalist/brutalist architects – my heart is with them. Burning Man, for its freedom, spontaneity and its “f-you” to the art world. Rolfing and other body work. Psychedelics. The Biospherians and Sanyasans I hung out with when I was young. Writers like Nabokov, Dostoyevsky, and the really naughty ones, like Bukowski and J.P. Donleavy.

Tom Robbins was an important mentor, and so was John Perry Barlow. Gordon Matta Clark, who I never met, is the artist I probably take the most from. And there’s James Turrell, who I know and love. Laurie Anderson. Absolutely Fabulous and Monty Python. Marilyn Monroe, Jessica Rabbit and Angela Merkel.

Then there is my greatest inspiration. It came in the form of five barrels. Biologist John Todd poured raw sewage into barrel one, along with a menagerie of living organisms – bacteria, algae, plants, frogs, fish. After two weeks, the stinking sludge was transferred into barrel two, and once again, all the living organisms were added. Two weeks later the sludge moved into barrel three and once again the organisms were introduced. And after six barrels, hallelujah! clean water. It may as well be the transubstantiation of Christ, but it’s just what nature does. It is the ultimate art. It’s a force that comes through writing and music and design, if you are willing to be its instrument.

Kirsha Kaechele will speak at The Architecture Symposium: Ideas from the Fringe on Saturday 4 March 2023.

The Architecture Symposium is a Design Speaks program organized by Architecture Media, publisher of ArchitectureAU.com, and supported by Brickworks and the University of Tasmania. Click here to buy tickets.