Coincidentally, the principal of the Women’s College within the University of Sydney, Dr Amanda Bell, is reading the same novel as me, which the back cover describes as a #MeToo revisionist version of Greek mythology. Given that her college is the client for the new Sibyl Centre by M3 Architecture, it is perhaps less coincidental that she has chosen a book about a strong female character, Circe, who could look into the future, like the prophetess Sibyl. I suspect that Bell may have the same skill, as she has been a potent force in the expansion of an already progressive educational institution. The circular, multipurpose Sibyl Centre, woven into the fabric of the existing campus, has created an unambiguously contemporary architectural heart for the College, while master-planning moves of Platonic clarity have stitched the site together like some enchanted Circean island.

Opened in 1892, the Women’s College was the first university college for women in Australia and is significant not only for the female achievement it has nurtured (alumni and principals include Dames Marie Bashir and Quentin Bryce), but within the University of Sydney campus, where it occupies the highest terrain of the college precinct. Overlooking the religiously affiliated male residential colleges, this secular, women-only establishment was, from the outset, a statement of difference, both demographically and architecturally. Its fine Main building, designed by Sulman and Power in 1894 and “somewhere between Queen Anne and Italianate,” 1 rejected the orthodox stylism and typology of stone Gothic Revival cloisters in favour of tiers of outward-looking brick loggias and balconies, where the landscape gently rolls up to the building. Emblazoned in stone at the entry, the College motto, Together (deliberately not in Latin), summarizes a commitment to the collaborative empowerment of women. Bell suggests that there is something in the bricks and mortar of the place that has represented and fostered this common purpose; this intangible quality is skilfully perpetuated in M3’s Sibyl Centre.

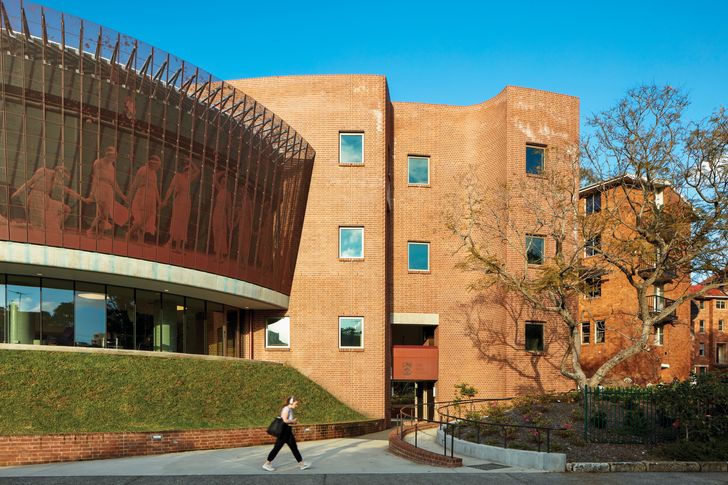

By stitching together the three arms of the existing Langley building with a circular plan, the new addition creates three protected courtyards.

Image: Christopher Frederick Jones

Lead architect for the project Michael Banney, however, describes the task as initially daunting, despite several fruitful prior projects with Bell when she was principal at Brisbane Girls Grammar School. Banney is a natural storyteller and, with characteristic humility, he recalls arriving at the College campus “in awe, and petrified at the prospect of working for this formidable institution.” Neither was the brief entirely clear: Bell was adamant that a previous masterplan was flawed, so M3 was effectively starting with a clean slate.

Appropriately perhaps (in the language of feminist rhetoric), the solution emerged not by concentrating on the “object” of architecture – a new building – but on “the other” – that is, site context and overlooked assets. The Women’s College had always been hampered by minimal land allocation, awkward juxtapositions with adjacent college buildings and expedient thoroughfares compromising its grounds. M3 identified coincident patterns and alignments in the 1960s Y-shaped Langley building and used it as the crux to resolve the “great mystery of site geometries” that had coalesced on the campus. Banney makes it sound obvious: “I simply stuck a compass into the middle of the Y and completed Langley … as if it were always intended.” But it was an inspired insight. The orbit generated from that point is translated into a circular “garden wall fortification” of diverse functions and circulation that stitches together the three arms of Langley and creates three protected outdoor courtyards. From this strategically permeable enclave, the Sibyl Centre blooms as a three-storey drum, negotiating and nudging the street. A berm concealing a level of carparking pulls up the landscape in the same manner as the adjoining campus terrain, so that the ground plane of the Sibyl Centre becomes simultaneously elevated and continuous with its surroundings.

M3’s first conspicuously circular project manages to avoid the usual pitfalls of this pure, bossy form. Externally, this is no disconnected pavilion, oblivious of its effect on the negative spaces around it; internally, the obstinate centrality of the footprint is offset by relaxing the symmetry and circulation patterns of the main space and its mezzanine tiers. In less formal mode, the Centre hosts a variety of table groupings and performance formats, but it can accommodate 250 people for lectures. Uninterrupted glazing at ground-floor level opens the complex visually and operationally to the world at large, at a time when transparency is a political and ethical imperative for any sequestered environment (and particularly for universities, post-Broderick Review 2 ).

Dry-pressed bricks in Flemish bond continue the constructional history of the College, while the precise carved masses are evocative of the work of Alvar Aalto.

Image: Christopher Frederick Jones

With its prosaic red-brick wings, Langley may have been more difficult to love than its elegant predecessors, but since it provided 50 percent of the College’s accommodation and was structurally robust, M3 saw the logic of retaining it and relished finding virtue in this hardworking facility. The new works adopt a language that both responds to and elevates the solid masonry bulk of Langley and its regular, rational composition. Banney invokes the story of the ugly duckling, but I prefer a more mythological metaphor: Circe might have turned men into pigs, but M3 has turned sows’ ears into silk purses with its clever transformation of Langley.

Stories infuse the Sibyl Centre in other ways, too. M3 describes an ethos of “looking backwards to look forwards,” drawing on anecdote and writing as ways to articulate dual perspectives in a project. Two tales of the College became pivotal prompts. In 1913, its first principal commissioned an allegoric play titled A mask, in which Sibyl retells the fate of famous women and looks to the future “to hint the tale of woman.” 3 Performed by diaphanously clad residents on the front lawn of the College, this provocative occasion was a thinly clothed “paean to female agency and call to action.” 4 In M3’s hands, a sepia photo of the event from the College archives became an encircling frieze for the body of the Sibyl Centre. This line of emancipated maidens, digitally replicated in perforated copper, instantly evokes the dancing caryatids of the Erechtheion at the Acropolis.

And these young women, privileged by education, needed to be light-footed as they trained to take their positions in a still-patriarchal society. The College was a place of emergence, and a story in its academic journal, Sibyl, suggests that the expansive verandahs of the main buildings provided conceptual and functional nurturing for women on the threshold of adult life. At the precipice: The balconies of Women’s College 1910–1960 describes how the spacious, sunlit balconies “became sites for play, experimentation and performance as well as places of study and sociability for generations of students.” 5 Supporting photos from the archive certainly show young women in all sorts of “testing” behaviours, from rehearsing exams to quaint high jinks and perilous perches on the balustrades. Accordingly, M3 deploys the balcony typology in the Sibyl Centre, not only as a generous patio circling the upper level, but also internally, with two levels of staggered mezzanines around the central auditorium. If contemporary building regulations prevent some of the edgier occupations of the past, in all other respects these spaces operate with the same unprogrammed and communal grace as their precedents; here, the pleasant prospect encourages students to relax, mingle and share a drink at sunset.

In less formal mode, the Centre hosts a variety of table groupings and performance formats, but it can also accommodate 250 people for lectures.

Image: Christopher Frederick Jones

The project is full of finessed understandings of the relationship between architecture and educational environments, in what Banney and Bell discuss as “the aesthetics of scholarship.” Beyond ancient spatial tropes (like the library, the dining hall, the study), this extends to high-quality light, air and acoustics, supported by robust, refined educational paraphernalia. The Sibyl Centre demonstrates a gentle balance between intimate and lofty space (for example, the sculptural timber-lined stair versus the curtain wall vista into the courtyard), and between decoration and durability, evident in the Mask frieze and the considered brickwork. Dry-pressed bricks in Flemish bond continue the constructional history of the College, but the precise carved masses are more evocative of Alvar Aalto’s work than nineteenth-century Free Style. Just like Aalto, M3 has used the modularity of bricks to temper scale and material homogeneity, with inventive elaboration of knitted corners, butterfly window sill joints and nuanced curvilinear surfaces. Having visited Frank Gehry’s Dr Chau Chak Wing Building (at the University of Technology Sydney) the day before, I reflected that the handling of brickwork at the Sibyl Centre is, by comparison, what my mother would have described as “neat but not gaudy.”

If I’m borrowing words from a previous generation of women to evaluate this building, I make no apologies. For this is a project that continues and manifests a legacy of intelligent women fostering a more inclusive society, and commissioning good architecture to achieve their aims. Moreover, it is a story of sensitive, informed responses by the architects charged with the task. Contemporary debates on equality are not for the fainthearted; nor are architectural expressions of gender uncontentious. Through its empathy for stories of places and people from the Women’s College, M3 Architecture has designed a satisfying and symbolically resonant home for the next generation of Sibyls, Circes and all manner of women game-changers.

— Rachel Hurst is a senior lecturer in architecture at the University of South Australia and a contributing editor for Architecture Australia. She researches everyday aspects of architecture through a baroque practice of making, writing and curating.

Footnotes

1. Zeny Edwards (ed.), The Women’s College within the University of Sydney: An architectural history 1894–2001, revised edition. (Sydney: Centatime Publishing, 2008), 12.

2. Elizabeth Broderick and Co., Cultural renewal at the University of Sydney residential colleges, The University of Sydney website, 2017, sydney.edu.au/content/dam/corporate/documents/news-opinions/Overarching%20Report%202017.pdf (accessed 6 September 2019).

3. John Le Gay Brereton and Christopher Brennan, A mask (Sydney: Women’s College, The University of Sydney, 1913), 7.

4. Tiffany Donnelly, “A mask: Centenary introduction,” 2013 reprint, in Sibyl: The Women’s College academic journal, vol 2, 2013, xii.

5. Tiffany Donnelly and Tamson Pietsch, “At the precipice: The balconies of Women’s College 1910–1960,” in Sibyl: The Women’s College academic journal, vol 3, 2014, vii–xviii.

Credits

- Project

- The Sibyl Centre

- Architect

- m3architecture

Qld, Australia

- Consultants

-

Acoustics

Acoustic Logic, Audio Systems Logic

Arborist Tree IQ, Raintree Consulting

Heritage consultant OCP Architects

Kitchen consultant Food Service Design Australia

Landscape architect Context

Quantity surveyor Steele Wrobel

Services engineer and Section J reporting Umow Lai

Structural engineer AECOM

Surveyor Hill and Blume

- Aboriginal Nation

- Built on the land of the Gadigal people of the Eora nation

- Site Details

-

Location

Sydney,

NSW,

Australia

Site type Urban

- Project Details

-

Status

Built

Completion date 2018

Design, documentation 14 months

Construction 16 months

Category Education

Type Universities / colleges

Source

Project

Published online: 22 Jun 2020

Words:

Rachel Hurst

Images:

Christopher Frederick Jones

Issue

Architecture Australia, March 2020