We are habituated to seeking in works of architecture a singular concept that insists itself at all scales and in every decision, from spatial organization to the profile of a ceiling cornice. It is this Wagnerian ideal of an organic whole that finds its way into our everyday critical language when we praise a project for “hanging together” or denigrate it as “incoherent.” The new research and learning building for the Faculty of Architecture, Building and Planning at the University of Melbourne stubbornly resists coalescing into a single memorable image or figure. It is an assemblage of architectural moments without obvious hierarchy or unifying aesthetic logic. Many of these elements are familiar tropes in current buildings of similar program: Bond University’s Abedian School of Architecture also has a sloping “topographic” ground floor; the entry stairs to the Chinese University of Hong Kong’s new building for the School of Architecture are used as an informal theatre; and the organization of research and learning spaces around an atrium crossed by feature stairs is almost ubiquitous. The Melbourne School of Design is, nevertheless, the mature and considered work of two extraordinarily talented practices, John Wardle Architects and NADAAA. Its heterogeneity is intended and fought for. Like asking us to compare a novel with a collection of short stories, it challenges us to find the appropriate critical language with which to appreciate its effects. I swear to do my best.

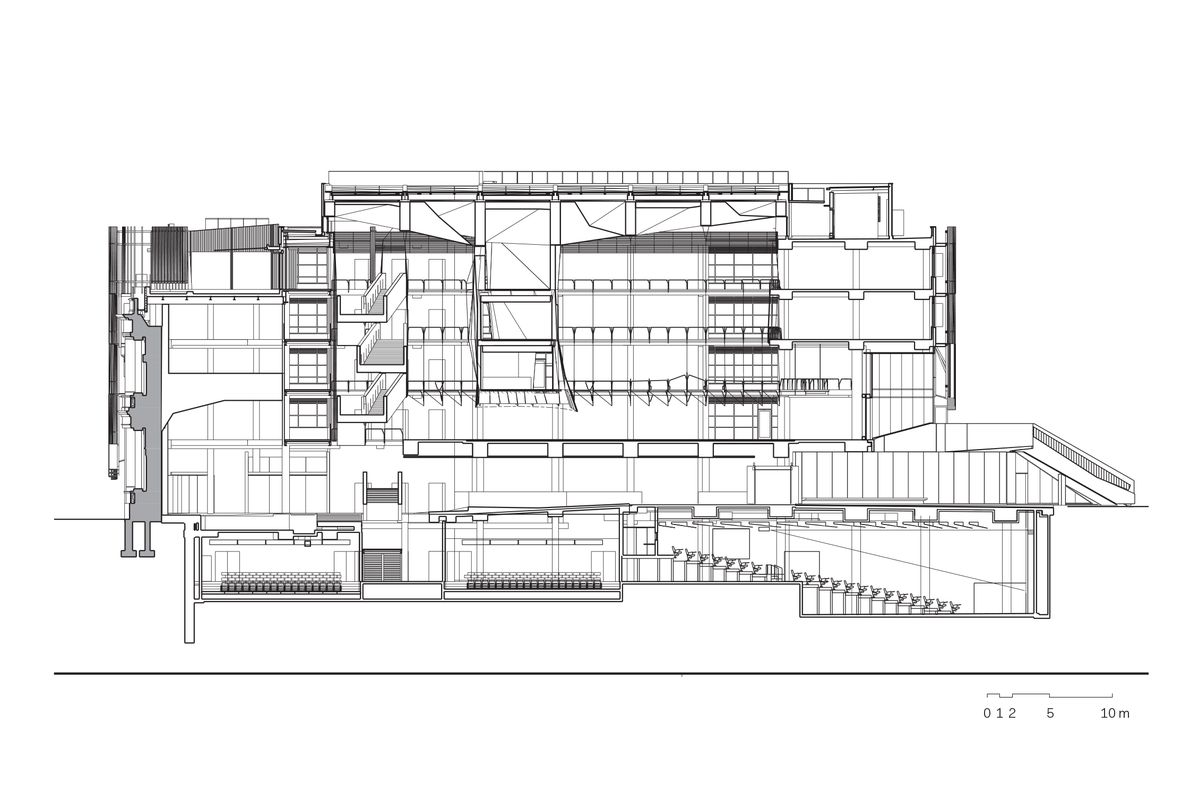

With each of its sides facing existing structures and spaces of variable character, the new building responds with four markedly different facades. There are multiple entries, none of which declares itself as the front or main entry. The building’s boldest spatial gesture, a four-storey atrium that rises from the first floor and has a dramatically coffered ceiling, has almost no presence externally or from the ground floor. A diminutive square of glazing set into the floor of the atrium to tempt newcomers offers only an obscure view from the ground floor. It is likely that students from outside the faculty who attend lectures in the auditoria in the basement will come and go without the hoped-for insight into the life of the academic community above them. The gallery, too, is curiously veiled. It is radically open from above, but the height of the opaque balustrade means it is possible to pass by unaware of its existence. For Tom Kvan, Dean of the Faculty, these hidden qualities destine the atrium to become one of those secret places on campuses that are discovered only by the curious. In the same conversation, Kvan talks up the integration of the faculty’s students and curricula and the building’s openness to the public. It is a curious tension, not altogether unpleasant, and very much the outcome of a process in which no single voice dominated and of a brief that presented multiple, sometimes contradictory, aspirations.

At the eastern edge, a large external stair leads students up to the atrium level and also serves as an outdoor amphitheatre.

Image: Peter Bennetts

First, to the process: Kvan describes the design as the outcome of a three-way research partnership between the faculty and the two architectural practices. Unquestionably, the faculty presents an unusually informed client. The competition framework, coordinated by Dr Scott Drake, emphasized that the criteria for selecting the architects would be their ability to address four core ambitions: make visible what each of the disciplines in the faculty contributes; create an outstanding place to work and carry out research; provide an exceptional learning environment centred on the design studio; and showcase the best techniques for environmental performance. The faculty knew what it valued, and entered into the process without a preconceived formal solution. Australian practice John Wardle Architects (JWA) and American studio NADAAA were selected for the quality and equality of their partnership. Although the two architectural practices had not previously collaborated, their entry conveyed mutual admiration and a clear understanding as to the very real differences each brought to the project as well as their shared interests. Territorial working or task demarcation, typical of other associations between architects, was never on the cards.

Nader Tehrani and his team in Boston and John Wardle and Stefan Mee and their office in Melbourne took advantage of the half-day difference in time zones to set up a toing and froing of ideas and critique. It is only just possible to see the hand of one or the other in certain details. The woven safety mesh balustrading is something Tehrani used recently for the Cornell University Bridges and the Hinman Research Building at Georgia Institute of Technology in 2011. The wrapped Marmoleum on the floor and walls of the Lovell Chen lounge is a familiar Wardle detail, used extensively at the SciTech Library for the University of Sydney (2008). Broadly, however, the architecture is genuinely the work of both practices, merging NADAAA’s digitally fostered rigour with JWA’s sensual approach. In the place of a single, author-driven aesthetic, the collaboration has yielded an abundance of ideas and well-tested details.

The Lovell Chen lounge connects to the rear of the Joseph Reed facade. The main exhibition space can be seen below.

Image: John Gollings

If the pairing of two brilliant practices already sets up the conditions for a weaving of multiple visions, aspects of the brief add further variance. The design was challenged to take into account spolia in the form of the 1856 stone facade of the former Bank of New South Wales by architect Joseph Reed and an entire room – the Japanese Room – and with it a Japanese Garden. These elements, which were already curiously dislocated from their original sites and cultures, have been impressively reinterpreted. The projection of a kind of materialized shadow from behind the old facade has been the occasion for virtuoso form-making. There were also artefacts of heritage value – murals, stained-glass windows, statues and sculptures – and these have been incorporated with a sensitivity of placement reminiscent of Carlo Scarpa’s oeuvre.

Intangible heritage – although not articulated in the brief – came with the users, as it invariably does. Several of the academics have unbroken histories in the faculty dating back to their student days in the 1970s and 80s, and with this long association came firm ideas about their workspace. Which isn’t to say that anyone felt nostalgic regret for the building this one replaces. Rather, conservative views required careful negotiation in the face of a brief that spoke of innovation, flexibility and change as key drivers. The mix of individual and group zones in the workspaces demonstrates a diplomatic compromise between providing for the contemplative solitude of traditional scholarship – at which this faculty excels – and the collaborative practices of new forms of research.

Studios on the first floor have pivoting doors that open onto the atrium, allowing for porosity and peer interaction.

Image: Peter Bennetts

Learning spaces, too, are a mix of large raked-floor lecture theatres for enduring forms of delivering content, and smaller flat-floor rooms for seminars and studios. These smaller rooms have pivoting doors that open onto the atrium to allow the kind of porosity that encourages peer interaction – a feature which all great architecture schools possess and which has now become fashionable in other disciplines. Sadly, the tradition of students taking up residence in the studios will not be possible, although there is provision for informal occupation around the balconies of the atrium.

The building’s boldest spatial gesture is its four-storey atrium, which rises from the first floor and features a dramatic coffered ceiling.

Image: Peter Bennetts

The aspiration for the building itself to be a kind of learning resource adds further complexity. The building was to address each of these six discipline areas in the faculty: architecture, landscape, urban design, property, construction and planning. Given a tight site, the emphasis has been on expressing construction and environmental performance. Glass showcases reveal mechanical plant room and footings, and the structure is exposed where it adds formal drama. The decision to use fixed sunshades of varying porosity and density instead of high-performance glass aims to make the building’s response to solar orientation more evident. Made of a muted zinc and attached to a clumsy frame of square profile, this veil of perforated screens is perhaps the least successful part of the building’s elevations; the lacy quality anticipated by earlier renderings translates only when looking out. There are several other gestures that are intended to raise questions about how they are achieved. The suspended stalactite of timber-lined rooms in the atrium is the most significant of these demonstrative inclusions. It and the coffered ceiling from which it seems to grow are undoubtedly dramatic. The spaces within this suspended volume may be a challenge to use: they vibrate as you move within them, which is great for registering their engineering, but also a little disconcerting. This is an artefact of pure formalism and unabashed exhibitionism that is likely to become the photogenic fragment that represents the faculty.

Lastly, the staging of parts of the program aims at a pedagogical statement. On entering from the east at the ground floor, one is greeted by the workshops to the north and the library to the south. The intention is to provocatively juxtapose two different forms of learning, reflection and making. The top-lit subterranean flank to the library is one of the most affectively powerful spaces in the entire building, its wishbone structure a thing of genuine beauty. That said, the separation of library and workshop – from each other and from the studios – speaks to a model of architectural learning that is challenged by new desktop digital technologies for fabrication and information. This is not to say that libraries and workshops are superseded, rather that their isolation will present a challenge to the fluid movement between internet research, digital modelling and analog drawing. If the organization of spaces speaks metaphorically about the relationships between activities, then the seclusion of academics and higher degree research students presents a particular demarcation between these activities and the learning of undergraduates that has been challenged in other faculties of this type.

The essence of the Melbourne School of Design building lies in what Marshall McLuhan coined the “resonant interval.” The spacing of each moment of a potential itinerary is the crucial achievement. Across an otherwise neutral backdrop of pale timber and grey paint, panels and concrete, we encounter small but intense splashes of vivid colour. The student lounge is a truncated triangle of red spanning a void. Tall alcoves beside the theatres are in Yves Klein blue. The computer laboratories sport a long visor of turquoise glass. The workshops are floored in bright orange and red. In the otherwise neutral staff lounge is a moss green banquette. Along the stairs is a folded plane of black and the desks around the atrium make a chain of diamonds in the exact shade of green that drawing boards once were. Like Paul Klee’s paintings, there is no perspectival centre or focal point, but a great deal of energy. John Wardle Architects and NADAAA have responded to the daunting challenge of designing a building that will receive more than the usual scrutiny from professionals in the built environment with meticulous detailing, rigorous self-criticism and an abundance of ideas.

Read William Cassell and Jonathan Russell’s interview with John Wardle Architects and NADAAA.

Credits

- Project

- Melbourne School of Design

- Architect

- Wardle

Melbourne, Vic, Australia

- Project Team

- John Wardle, Stefan Mee (principals-in-charge); Meaghan Dwyer (senior associate); Stephen Georgalas (project manager); Bill Krotiris, Andy Wong, Jasmin Williamson, Adam Kolsrud, Alex Peck, Barry Hayes, Jeff Arnold, Amanda Moore, James Loder, Danny Truong, Stuart Mann, Meron Tierney, Kenneth Wong, Sharon Crabb, Yohan Abhayaratne, Rebecca Wilkie, Ben Sheridan, Giorgio Marfella, Kirrilly Wilson, Elisabetta Zanella, Adrian Bonaventura, Genevieve Griffiths, Michael Barraclough, Matthew Browne, Maria Bauer, Anja Grant (team), Nader Tehrani (principal-in-charge); John Chow (project manager); Arthur Chang (design coordinator); Katie Faulkner, James Juricevich, Parke MacDowell, Marta Guerra Pastrián, Tim Wong, Ryan Murphy, Ellee Lee, Kevin Lee, Rich Lee (team)

- Architect

- NADAAA

United States

- Consultants

-

Accessibility consultant

One Group ID

Acoustic consultant AECOM

Audiovisual consultant Avdec

Building certifier McKenzie Group

Building services Umow Lai

Building sustainability commissioning agent A.G. Coombs

Civil and structural engineer Irwinconsult

ESD Umow Lai

Electrical and mechanical engineer Aurecon

General contractor Brookfield Multiplex

Geotechnical engineer Douglas Partners

Heritage architect RBA Architects and Conservation Consultants

Interior designer Wardle, NADAAA

Landscape architect Oculus Landscape Architecture & Urban Design

Lighting designer Electrolight

Project manager Aurecon

Quantity surveyor Rider Levett Bucknall – Melbourne

Security Aurecon

Traffic engineers Cardno

- Site Details

-

Location

Melbourne,

Vic,

Australia

- Project Details

-

Status

Built

Category Education

Type Universities / colleges

Source

Project

Published online: 15 Apr 2015

Words:

Sandra Kaji-O'Grady

Images:

John Gollings,

John Wardle Architects and NADAAA,

Peter Bennetts

Issue

Architecture Australia, January 2015