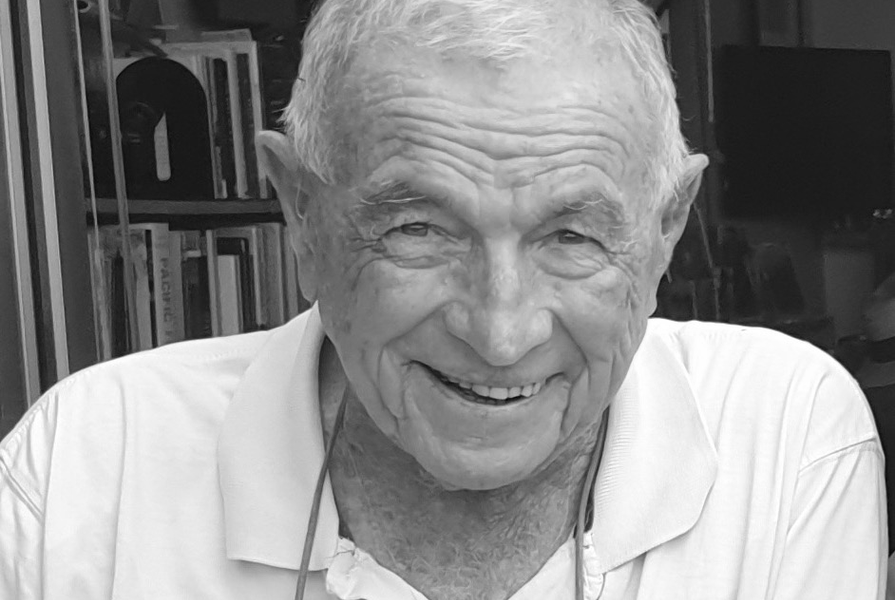

Architect Peter Heathwood recently died at the age of 90 years. We will remember him in many ways, but for me, he was both a gentleman and an inspiration. Born and later practising in Brisbane, he was destined to become an architect. He once confided that at age 10 (1942), he was drawing houses with flat roofs that were to be used as helipads. Schoolwork was of little interest, and he failed to pass the Scholarship and Junior examinations, instead seeking work with the Brisbane City Council. Fortuitously, he followed his mate Robin Gibson to the Works Department of the Council and was mentored by the city architect and planner, Frank Costello. It was here that Heathwood met John Dalton, who was some five years his senior and newly arrived from Britain.

Costello encouraged Heathwood to enrol in the architecture course at Central Technical College in George Street. To do so, he needed to pass his Senior examination; in 1950, he studied at night and passed the exam in one year. In 1951, he enrolled in architecture, which was also taught at night. By 1952, there were only a handful left of what had been approximately a 30-person cohort, but all those who remained stayed the distance and graduated in 1956.

When Mayor Chandler was defeated by Labor’s Roberts in 1952, there was a purge of senior staff from the Council – and it mysteriously included junior draftsman Peter Heathwood, who had already decided to move on. The press gave the story front-page treatment, and Heathwood became a minor celebrity. Heathwood’s friend Robin Gibson at Thynne and Hitch, then one of Brisbane’s most progressive architectural studios, suggested that Heathwood come and work there. For the next 18 months, he did so in good company: Don Winson, Ian Charlton and John Dalton were among his co-workers.

Heathwood next moved to the office of Job, Collin and Fulton. The three partners in this practice had each taught him in the course of his study. After 18 months, he moved again, seeking as much variety of experience as possible. At Crick, Lewis and Williams, his design skills were recognized. Heathwood became the designer for the practice and was responsible for the design of now-demolished Festival Hall, as well as several Ampol petrol stations. His next employment was with Job and Froud, who were engaged on Torbreck at Highgate Hill. Heathwood worked on the eight-storey garden block, which was built first.

1956 Speare House, Indooroopilly, designed by Peter Heathwood.

Image: Supplied

At this time (1956), he entered a competition to design a house built of plywood. John Dalton also made an entry; they agreed that if either design won the £3,000 prize, the pair would use the money to start a practice together. Heathwood’s design won, and John Dalton documented it while Peter Heathwood went on his honeymoon. He and his bride, Helene, stayed in the newly completed Lennon’s Broadbeach Hotel, which was designed by Karl Langer. The plywood house Heathwood designed was built in 1957 at the Brisbane Exhibition Grounds and visited by thousands, raising the new practice’s reputation for competent modernist design. The house, which Heathwood later extended for his sister and brother-in-law, survives and has been relocated to Brisbane suburb The Gap.

Heathwood’s most influential work, for me, was a house he designed in 1956 – before he had even completed his architecture course. When the home of his friend George Speare burned down, Heathwood designed a simple but radical replacement for a site at Indooroopilly. The house had a flat roof with a raised central clerestory and a nearly continuous lattice screen for privacy, sun protection and ventilation. The edge condition meant that the screen met the generous roof overhang and gave the building a particularly modernist aesthetic that was also a recognizable regional variant. In the two places where there was no screen, the wall stepped back to form a useable verandah. This house demonstrated how a modernist pavilion could be adapted to suit Brisbane’s climate and traditions. Tragically, the house – which had been widely published and was acknowledged in 1959 as one of the 10 best houses in Australia – was recently demolished to create two vacant blocks.

After 18 months in partnership, Heathwood separated from Dalton. Heathwood’s subsequent practice produced many quality houses on miniscule budgets; at its peak, the practice had 24 employees. Many students were mentored through their courses while employed there, and in 1975, the practice evolved into a partnership known as Heathwood Cardillo and Wilson. Heathwood’s younger brother Roger joined the partnership in 1972, becoming a director in 1983. In Heathwood’s opinion, some of its best work included the Medical Services building at the Rockhampton Hospital and the Law School at QUT – but Heathwood’s favourite remained the Speare house, which he insisted was a labour of love.

Heathwood retired from active practice in 1993. After architecture, his greatest passion was on the water: he had owned several yachts and devoted some months each year to boating activities. He always maintained that he would rather be sailing.

Heathwood remained in good health until his death. He is survived by his wife, Helene, and children Petrea, Cameron, Tania and Ian.