Scotland island is a short boat ride from the mainland via Pittwater estuary – an hour’s drive north of Sydney. We make the trip in a five-metre timber runabout that Greg Roberts built by hand some years ago.

From the water, the corrugated roofs of the Pitt Point House protrude like huts among the trees, their grey/green cedar weatherboards blending into the bush. We tie up at a pontoon and walk the sixty-metre jetty to Greg’s boatshed, then up to the sandstone terrace and outdoor room that Greg and wife Louise enjoy year round.

Scotland Island is home to just a few hundred permanent and holiday residences. To its north and west is Ku-ring-gai Chase National Park, to its east, the Northern Beaches peninsula. Pitt Point House is unique among these residences, being one of only a handful of true north-facing waterfronts in the Pittwater, which stretches from Newport up to Barrenjoey Head, where the Hawkesbury River empties into the Pacific.

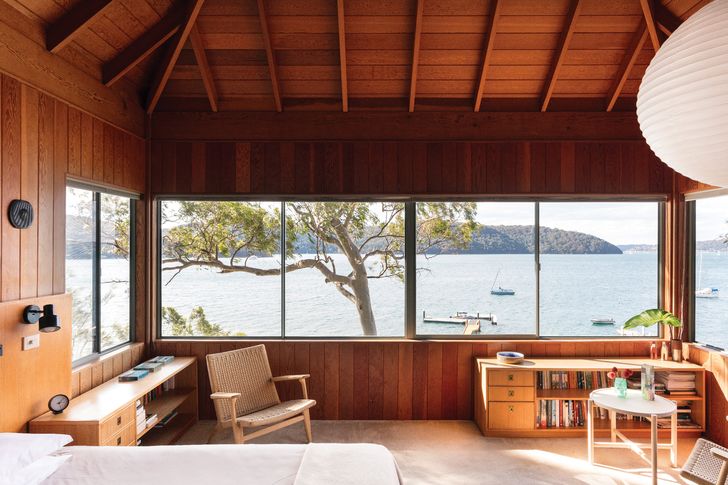

The main bedroom, under a steeply pitched roof, offers views north up the Pittwater to Barrenjoey Lighthouse.

Image: Tom Ferguson

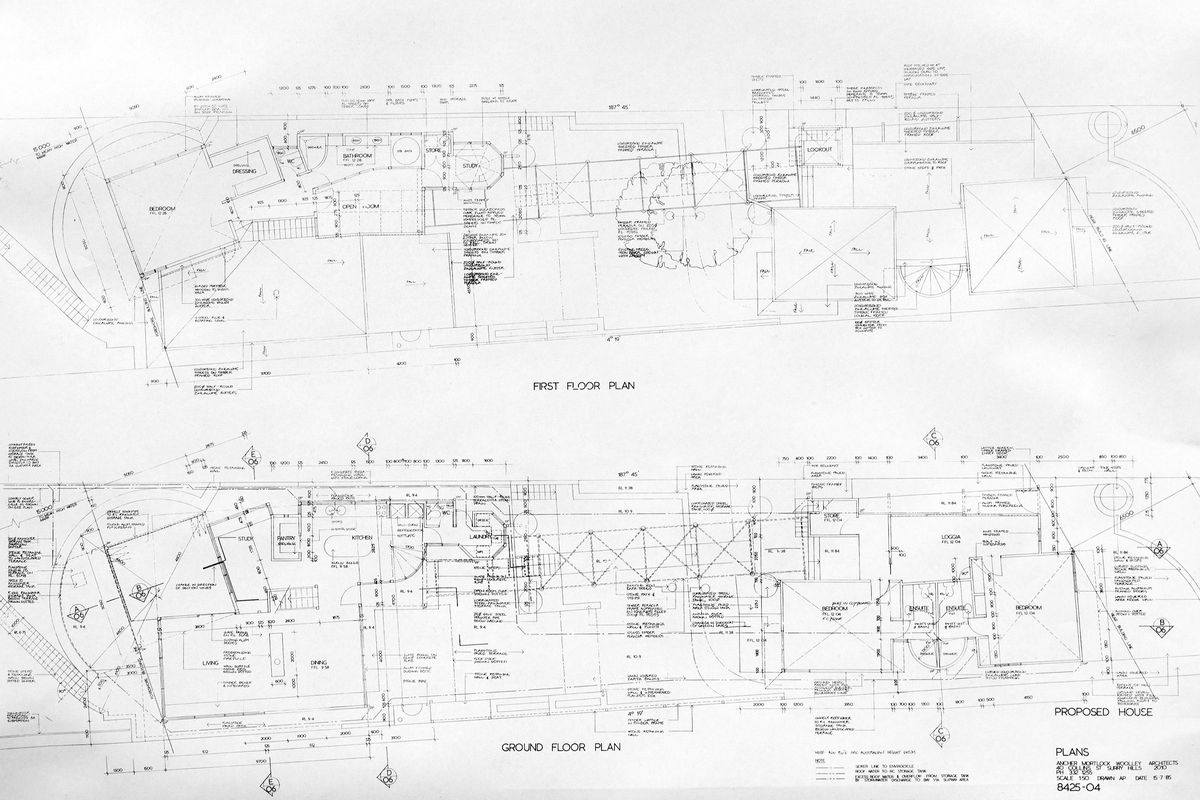

Built on a long, narrow site in 1985, this island retreat was designed by Ken Woolley for his friend and longtime collaborator Brian Pettit. Woolley was a prominent mid-career architect by then, a principal of Ancher Mortlock and Woolley, and working on the Commonwealth Law Courts at Parramatta. Pettit was a keen sailor and gregarious businessman and developer behind the home-building company Pettit and Sevitt, which had closed its doors in 1978.

Though the house was intended as their weekender, the Pettits lived in it permanently for ten years – entertaining lavishly and often – before selling to the current owners, Louise and Greg, who are also boating and design enthusiasts. Notable guests of the Pettits had been the Fijian High Commissioner (at Brian’s sixtieth birthday party) and former prime minister Bob Hawke and his second wife Blanche d’Alpuget, who honeymooned there in 1995.

The house is a collection of buildings and shapes in a seemingly ad hoc arrangement, “as if they had developed over time,” according to Walter Barda, who was an associate director of Woolley’s practice at the time and produced designs and drawings for the project.

“The idea was a small village of clustered vernacular elements: main house, water tower, [the guest wing] – it’s an island house after all. To that we gave skewed geometries and overscaled pitched roofs chopped in half [living room and main bedroom]. From an aerial perspective, the plan kind of wiggles through the site, some of its elements intersecting or colliding. It’s all very informal but structured.”

Being ostensibly an adult retreat, its key spaces are the living area, overlooked by a luxurious main bedroom. These are gathered up under two steeply pitched roof peaks, intersecting above the stairs. Both the living room and bedroom face north with views up the Pittwater to Barrenjoey Lighthouse, winking at night.

A collection of buildings and shapes in a seemingly ad hoc arrangement, the house was designed to resemble a small village.

Image: Tom Ferguson

Behind the bedroom, the plan splits under a shallow skillion roof with a skylit ensuite, terracotta tiled, followed by two interconnected studies, facing west and south into the rear bush garden – a feature of most Woolley houses, along with meticulous craftsmanship.

Walls, posts and beams and the cathedral-like ceilings are all clear-finished Oregon, sculpted with millimetre precision by a team of German carpenters. It’s reminiscent of other notable works by Woolley, including his own house at Mosman and the stunning St Margaret’s Chapel in Surry Hills – his first independent commission.

The living room opens to the northerly waterfront terrace through floor-to-ceiling glass. A low wall of timber joinery housing a fireplace and bookshelves partitions the more enclosed dining room, facing south onto the rear terrace. The nearby all-white kitchen, still in excellent order, also opens to the rear terrace, where the procession of outbuildings and structures includes an arbour, a watchtower, water tanks, a series of cascading ponds and the more introspective guest wing. Facing into the garden, the two bedrooms with ensuites and a screened-in sleep-out are also timber lined under steeply pitched roofs.

Certain details, like the living room’s corner bar and the large sunken circular bath upstairs, might suggest Pitt Point is more of an “offshoot” than a typical Woolley house, reflecting the architect’s unique relationship with Pettit, for whom he built many private homes, and more.

Woolley and other great Australian architects – Michael Dysart, Harry Seidler, Russell Jack and Neil Clerehan – had all designed affordable housing for Pettit and Sevitt, which built around 3,500 homes through the northern suburbs of Sydney and Canberra from the early 1960s to 1978.

Corrugated roofs protrude like huts among the trees, while cedar weatherboards blend into the bush.

Image: Tom Ferguson

Coincidentally, Greg and Louise’s first home was one of Pettit and Sevitt’s earliest Lowline designs by Ken Woolley, built in 1964 at Elanora Heights. Greg had grown up with design. His father Russell had been a boat designer/builder and a commercial photographer. His aunt was the flamboyant modernist illustrator, designer and milliner, Hera Roberts. They could have never settled for an ordinary house.

“We had an architect draw up plans when we were first married, but they were out of our budget,” recalls Louise. “So a friend told us to take a look at this new company, that was Pettit+Sevitt. The Lowline design was exactly what we were after, and they let us customize it with recycled sandstock bricks and a deep-red sandstock fireplace.”

What had set the now iconic Pettit and Sevitt apart from other project-home developers was its focus on design, craftsmanship and connection to landscape – which are also the hallmarks of Pitt Point House, a dwelling virtually unchanged by the decades. Over more than twenty years, Greg and Louise have altered very little here, except to renew the kitchen floor, replace a glass shower screen and discreetly add a timber balustrade to the upstairs landing.

That the house has endured so well is testament not only to the Roberts’s stewardship, but also to a skilful balancing of opposites in its design – light and shade, prospect (a lens to the view) and refuge (a cocooning space from which to view it). A variety of moods and architectural moments are orchestrated within a relatively modest footprint, and its passive environmental design measures are as relevant today as ever: cross-ventilation, roof and wall insulation, and shallow awnings (“eyebrows,” as Greg calls them) that allow winter sun to flood through the big picture windows while blocking it in summer. “It’s a very comfortable house to live in.”

Woolley once said there was not much point practising architecture unless it was “approached as an art form.” Pitt Point House captures the island spirit not only artfully, but also playfully. What appears from the water as a prosaic pair of huts unfolds into something infinitely more satisfying, primal and complex. A treehouse and a cave, right on the water’s edge.

Credits

- Project

- Pitt Point House

- Site Details

-

Site type

Coastal

- Project Details

-

Status

Built

Category Residential

Type New houses

Source

Project

Published online: 4 May 2018

Words:

Peter Salhani

Images:

Tom Ferguson

Issue

Houses, February 2018