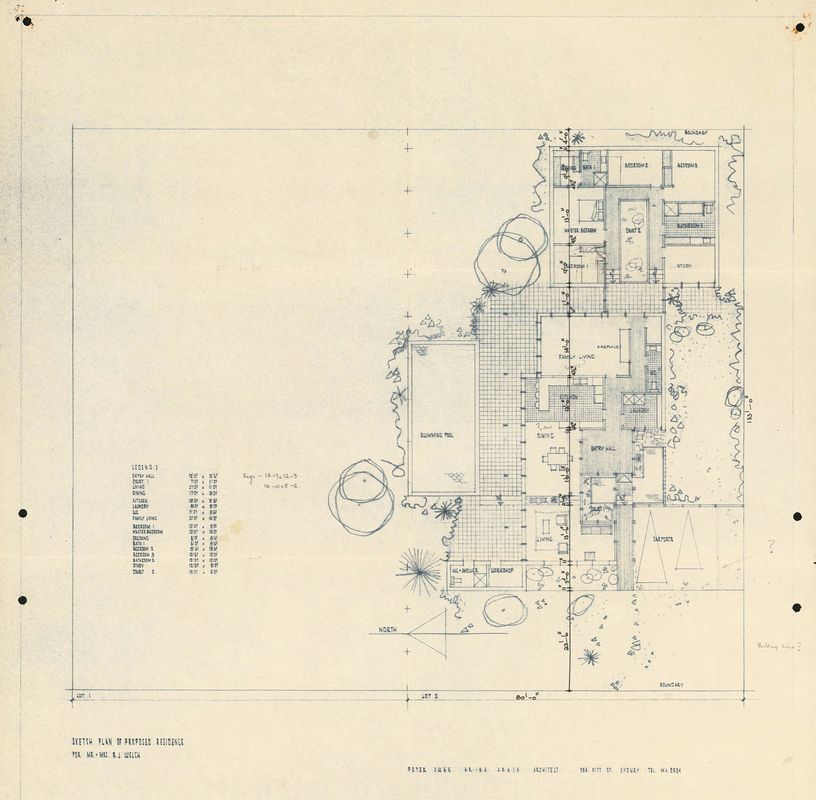

The Welch House in the Sydney suburb of St Ives is something of a mid-century anomaly in that very little is known about its creator. Architect Peter Swan was commissioned by Rhoderic and Marjorie Welch to design a house for their family in about 1962. Why Swan was chosen is not clear, nor do we know a lot about the work of Peter Swan. We do know that he designed a series of drive-through banks in the Sydney suburbs of Burwood, Ashfield and Bankstown for the English, Scottish and Australian Bank in the late 1950s and that, by the late 1960s, he was in partnership with Allan “Barry” Holt. Marcus Lloyd-Jones, founder of mid-century-specialist real estate agency Modern House, has identified three other houses that may have been designed by Swan, although he can’t be sure they were of his hand.

The house was bought from the Welchs by the Payton family, who have lived in the house since 1974. John Payton, who grew up in the house, described it as “a good place to live. It’s the kind of house that works well for all different ages.”

In the family living area, a wall of sandstone serves to ground the space.

Image: Anthony Basheer

While the commission and owners’ history of the house are known, the lineage of thinking behind its design is a mystery about which we can only speculate. We don’t know if it is typical of the architect’s work, nor if it is indicative of a particular interest or approach. However, by examining the house as it stands today, we can speculate about how it might have been thought about.

Comparisons have been drawn between the house and the work of a number of local architects practising at the time, yet the provenance of the general planning approach and tectonics may be found further afield. It could be argued that the house shows characteristics of the planning strategies employed by Rudolph Schindler in his own Kings Road House in Hollywood, Los Angeles, completed some 45 years earlier. Kings Road House was arranged for two couples (essentially two studios with a shared kitchen) and Welch House, too, is split – albeit in a more simplistic way – into public and private spaces for a single family. Looking for a local precedent, similarities can be drawn with Neville Gruzman’s Benjamin House, completed four years earlier in nearby Longueville. It could be posited that Gruzman took Schindler’s planning principles and adapted them to local conditions, and that the scale, tectonic approach, detailing and materiality of Benjamin House have parallels with the approach taken later by Swan.

The kitchen is detailed in Tasmanian blackwood and has sheet vinyl flooring, Laminex benchtops and a copper rangehood.

Image: Anthony Basheer

The east–west aspect of the quarter-acre block in St Ives allowed Swan the opportunity to stretch the house in order to gain maximum access to northern sun and southern light. However, Welch had to argue his case with council for breaking the “arbitrary 30’0’’ street alignment”, with the length of the site being a comparatively short 133 feet (40.5 metres). Welch wrote to council, stating, “As the building blocks are covered with trees and native shrubs, it is my intention to retain as much as possible of this growth and add further indigenous flora, so that the result will become a barrier between the alignment and the actual walls of the structure.” This rationale clearly sat well with the authorities, who allowed Swan to work to within four feet of the rear boundary and within twenty-three- and-a-half feet (a little over seven metres) of the street.

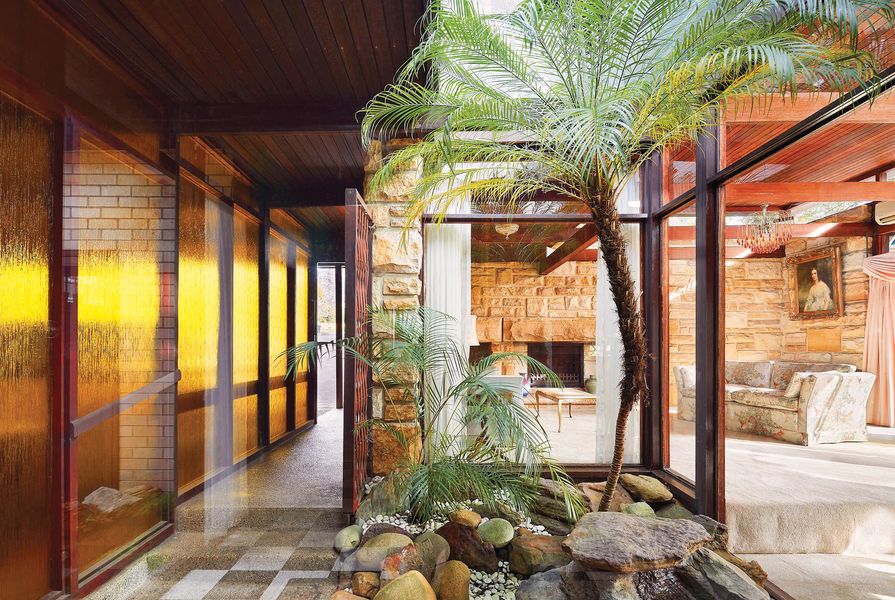

The two-pavilion arrangement of the house places the public spaces (living, dining, kitchen and family rooms) toward the front of the block, set behind a (now) towering eucalypt and between the northern yard and a carport. The entry sequence squeezes in a lobby with chequerboard floor tiles and incorporates a palm garden that once opened to the sky.

The entry sequence squeezes in a lobby with chequerboard floor tiles.

Image: Anthony Basheer

Suburban circumstance generally means the arrival at a home is by car, and this house is no exception. There is no footpath along the street, and so approach is, by necessity, via the driveway, where an entry portico serves as both carport and pedestrian entry. The car zone is separated from the people zone by an amber glass screen, the plane of which continues past the portico and across the southern side of the entry lobby. The whole entry sequence and formal living and dining spaces orbit a palm garden that, combined with high-level clerestory windows, shifts the sense of separation between internal and external space ever so slightly to set up a lovely feeling of lightness in the public areas. The front wall of sandstone with an embedded fireplace serves to ground the spaces at the same time as it provides separation from the street beyond.

The “separate” private wing at the eastern end encompasses four bedrooms and a study that wrap around a second, larger palm garden. The rooms, raised a few steps higher than the main living level, are all modest in scale with built-in blackwood joinery. “Coming out of your bedroom to be faced with vegetation was lovely,” says John. The bathrooms located within this wing are a wonderful surprise, with exquisitely detailed metal shower screens, coloured tiles and terrazzo tiled floors highlighted by skylights or high-level windows. These bathrooms are exemplars in showing that modest materials used well can lift a spatial experience.

The bedrooms are modestly sized but offer views to garden and greenery.

Image: Anthony Basheer

The true centre of the house is, of course, the kitchen. Detailed in Tasmanian blackwood, the room features sheet vinyl flooring, Laminex benchtops, a copper rangehood and vibrant floral wallpaper. These elements make the room an exquisite piece of 1960s interior design that was elegant, contemporary and casual all at once. “It was the focal point of the house,” John has said. “As a family, we used to eat at the bar. At the time, we had some bright orange stools, which kept with the lairiness of that era. I have very fond memories of that room – there was always a lot of chatter, and people pitching in with the preparation and cleaning up.”

With the Paytons now looking to move on, the house is set to move forward with another owner. Its quiet, aware design stands as a great example of pragmatic elegance. Unburdened by the label of a well-known architect, the house can be appreciated for what it is while also being flexible enough to adapt to any particular living scenario its new inhabitants might bring with them.

Architect: Peter Swan Project team: Peter Swan Builder: R. J. Welch of Welsh Bros

Source

Project

Published online: 11 Jun 2021

Words:

David Welsh

Images:

Anthony Basheer

Issue

Houses, October 2020