Artist Penleigh Boyd is suggested to have done his best work painting plein-air on the banks of the Birrarung/Yarra River, in the bushy outer Melbourne suburb of Warrandyte. His son, architect Robin Boyd, spent his earliest years here, scrambling around the garden of a picturesque cottage his father had designed and built near the river before he tragically passed away in a car accident when Robin was four years old. Warrandyte would have an enduring hold on Robin Boyd; over the course of his life, he designed and built at least seven houses in the area (excluding Small Homes Service projects), all of which were for artists. Many of the early houses followed a “Warrandyte idiom” characterized by rough-sawn timber and locally sourced stone. Following a disastrous bushfire that swept through the area in January 1962, Boyd was among those called on to rebuild. In the houses that followed, there was a startling shift toward a fire-resistant material palette and a more expansive spatial language. The second home designed for Joyce and James Wright was one such design, and it ranks among Boyd’s most compelling.

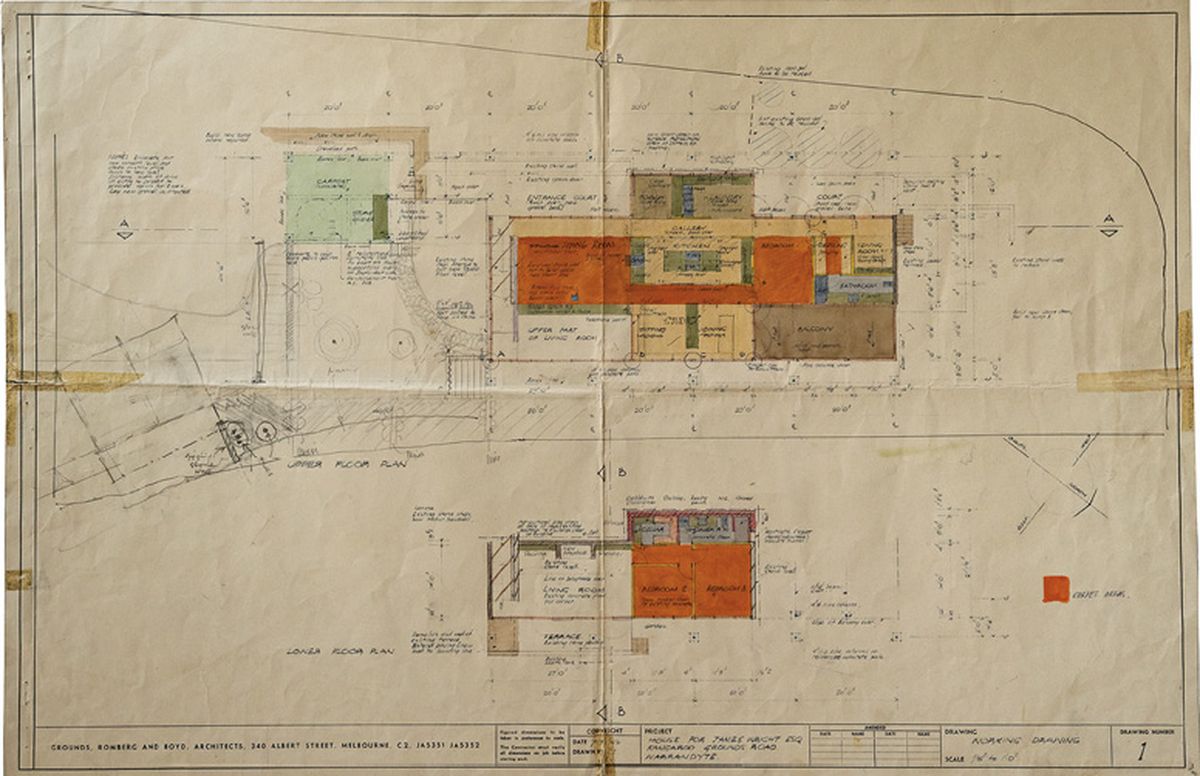

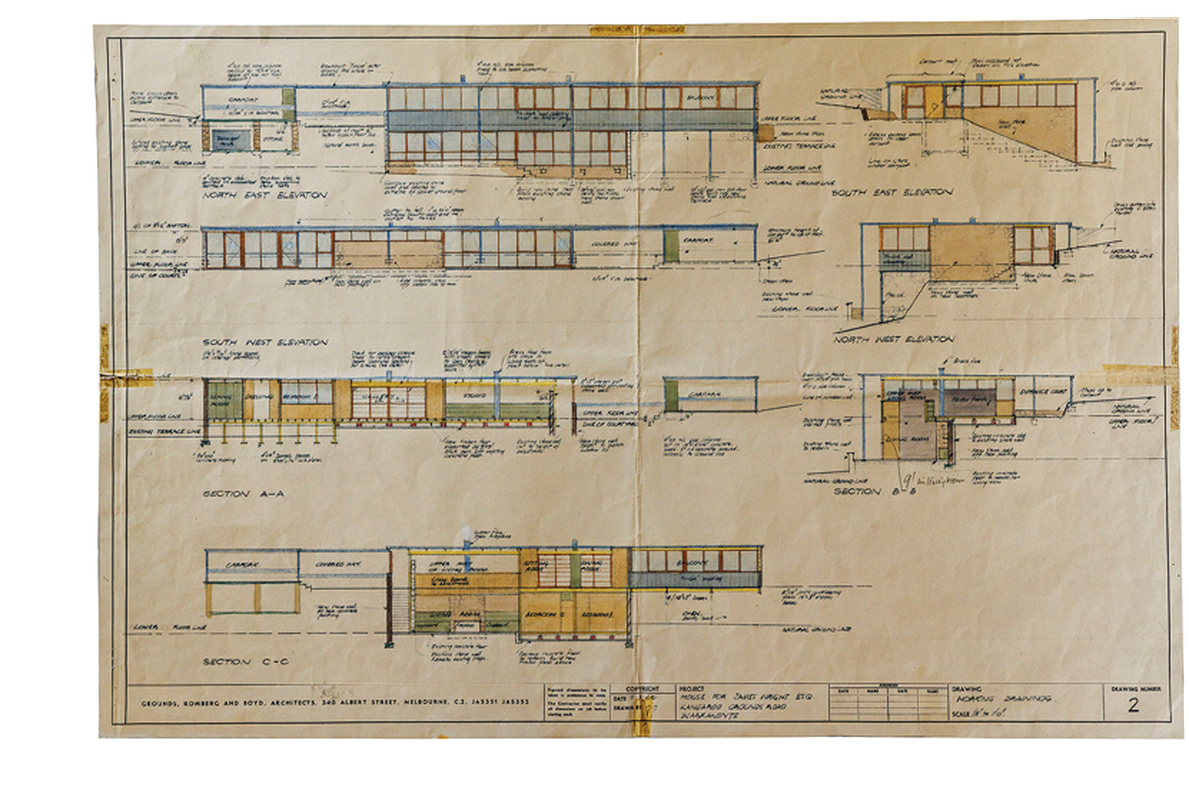

The first home Boyd designed for the Wrights – a long, skillion-roofed structure perched on a steep north-facing slope – was completed in the late 1940s. It was reduced to ashes in the fire, save for two stone walls. The second design, which remains today, incorporated these vestiges and substituted the timber wall cladding of the Warrandyte idiom with steel tray decking. The long side of the house’s rectangular mass is oriented north-east, looking out over Warrandyte State Park and parallel to the topography. A new stone wall was added along the short north-western side, but otherwise the entire perimeter of the house is wrapped in glass, affording views from most rooms into the beautiful bush setting. The large, single plane of the steel deck roof seems to float, and it extends out to rest on slender steel columns held off the building to provide deep, shading eaves. The fire-resistant skin of stone and steel was carefully detailed to ensure flying embers from future bushfires had nowhere to lodge. Wright House II was completed in December 1962, with Graeme Gunn undertaking the working drawings.

On the first floor, a cruciform plan creates distinct zones that are well-equipped for entertaining. Artwork: L. R. Parker.

Image: Dianna Snape

Inside, the house is ordered as a cruciform. On first glance at the plan, this arrangement might seem somewhat staid. However as soon as one enters and moves through the house, its brilliance and drama quickly become apparent. The Wrights were both commercial (graphic) artists who worked from home and loved entertaining. Consequently, in addition to the typical domestic requirements for cooking, living, bathing and sleeping areas, they needed a home studio, as well as formal living and dining areas. As the Wrights did not have children, fewer bedrooms and less spatial separation was required, which permitted greater freedom in how the different spaces could relate to each other. James Wright reportedly gave Boyd a sketch plan that, while crude and very different to Boyd’s final design, did include some of the more unusual room relationships.

An internal, sky-lit kitchen stands in the centre of the cruciform, enclosed by sliding doors with fibreglass insets (echoing Japanese shoji paper). The four arms of the cross are zoned as entry and laundry, sleeping and sewing, dining and studio, and finally living. Large sliding doors also project out from all four corners of the central kitchen, such that one is able to link and separate rooms as desired – or stroll right the way around. The cruciform arrangement thus offers continuity between the spaces, while granting each function its independence when required.

Sliding screens allow occupants to link or separate living, dining and cooking zones as desired. Artworks (L–R): Jan Riske, Stan de Teliga.

Image: Dianna Snape

The plan could also be read as a riff on the nine-square grid, a classic architectural trope stretching back to the work of Renaissance architect Andrea Palladio. Three of the four corners nestled under the roof are unenclosed, serving as entrance court, service court and verandah balcony. The fourth corner is brought into the glazed envelope and extends down as a double-storey void that connects the upper living spaces to a lower-level music and reading lounge. One of the two remnant stone walls reaches up through this void and screens the stone staircase behind. The staircase side of the wall is unfinished, combining with planting to create a beautiful, earthy transition space. In contrast, the lounge side is rough-plastered and painted white, its clean abstraction illuminating the interior.

The volumes of the main living spaces are defined by vertical and horizontal planes that float apart from each other, an architectural language Boyd often employed to create a wonderful play between connection and containment. One feels cosy and held in each room, but there is also a sense of flow and generosity. We can imagine how the spaces really came to life during the Wrights’ rambunctious parties. The lower floor was designed as an independent suite to accommodate guests, and it serves equally well as a home office for the house’s current owners.

Heavy gauge steel roof sheeting (considerably thicker than is commonly available nowadays) allowed for larger spans and thus sparser structure than was common for residential construction of the day. The Canite ceiling is set out in full-size, staggered panels with exposed, brass flathead nail fixings whose spare and precise spacing make the ordinary lining appear careful and craft-like. The chimney flue of the lower lounge fireplace passes through the higher living space and keeps both areas toasty.

The sliding doors are floor-to-ceiling and retract flush into wall cavities, their ceiling tracks concealed within double beams. Well ahead of their time as a design detail, they appear as seamless planes in the spatial composition. This integration is made possible by the carefully composed synchronicity of structure and space so evident in all of Boyd’s work. A previous owner is reported to have spent the first six months of their stay complaining about the lack of separation between the bedroom and dining room before realizing the flush pull in the opening was not merely a decorative feature.

A dramatic void at the north-east edge connects the two levels. Artworks (L–R): Ola Lau, Joan Miró (signed print).

Image: Dianna Snape

The Wrights later commissioned Boyd to add a separate office studio to the property, which was completed shortly before Boyd’s unexpected death in 1971. The house has had three subsequent owners, each passing down a set of the original working drawings. Modifications have been minor and are mostly limited to the kitchen fitout. The current occupants express that they have always felt more like custodians than owners, and remark how content they felt despite being confined to the house for many months during Melbourne’s COVID–19 lockdowns. The house has always felt generous to them.

The coherence of site, structure and space evident in Wright House II, and the simplicity of its overall parti, seem both hard won and effortless. Realized in an understated, natural palette and with robust detailing that preserves the direct expression of fundamental elements, the design feels relaxed and unselfconscious. But what really makes the heart sing are the varied scales and spatial play yielded by the language of floating planes. There is a quiet sense of serenity and connection to place that evidently nourishes and responds to the unique lives of those who’ve been fortunate to live here.

Author’s note: Tony Lee was consulted during the writing of this article. The author wishes to acknowledge and thank him for sharing aspects of his deep and ongoing research into Boyd’s work.

Credits

- Project

- Wright House II

- Architect

- Robin Boyd

Melbourne, Vic, Australia

- Consultants

-

Builder

Joseph Versteegen of P. M. Versteegen and Sons

- Site Details

-

Site type

Rural

- Project Details

-

Status

Built

Category Residential

Type Revisited / first house

Source

Project

Published online: 28 Oct 2022

Words:

Byron Meyer

Images:

Dianna Snape

Issue

Houses, October 2022