Head west out of Melbourne across the dry landscape, travel for just under an hour and, before dropping down into Bacchus Marsh, you will find yourself in the vicinity of a singular collection of architectural gems. The three buildings I am referring to make up the Baker Compound, comprising the Baker House, the Dower House and the Baker Library/studio. They were designed by acclaimed architects – the two houses by Robin Boyd between 1964 and 1968, and the Baker Library/studio by Roy Grounds in 1979.

I am tempted to say that the trip out to the Baker Compound is unremarkable, but in fact it is the opposite – remarkable for its display of the suburban sprawl, the “aesthetic calamity” that Boyd railed against in his written works. Enduring such ugliness does little to prepare the visitor for the sense of withdrawal and isolation still engendered by the final part of the journey to this special place. Once you’re at the property, the approach to the compound takes a winding path through the bush, further emphasizing the sense of separation. This distinctive mallee setting has a strong visual character, and it is almost monotonous in its uniformity.

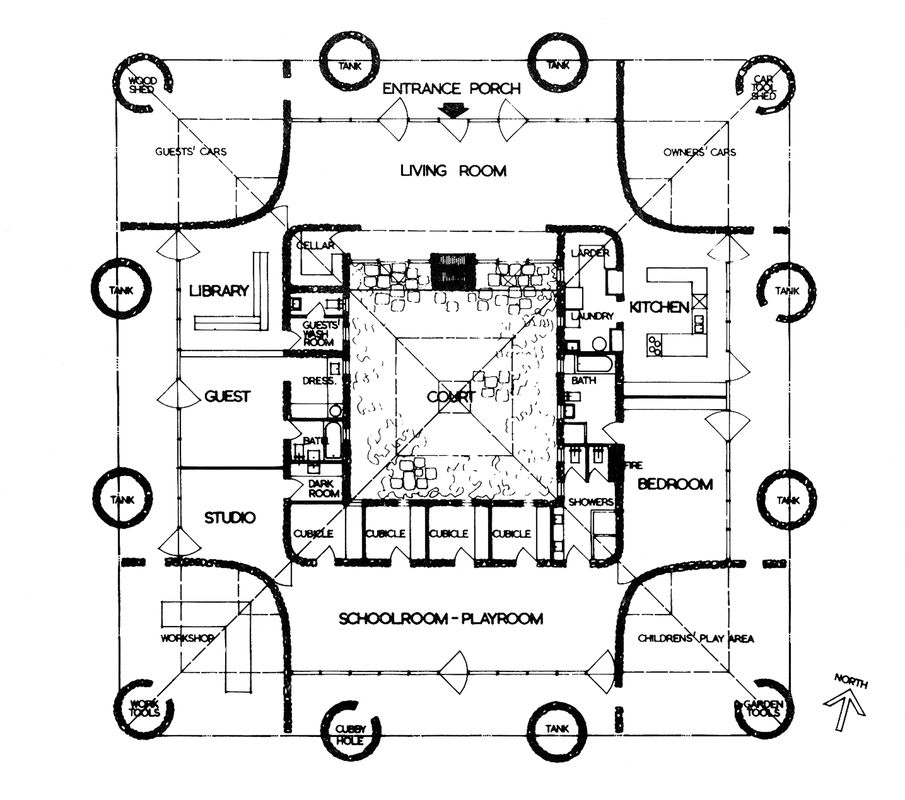

The Baker House is a ninety-square-metre dwelling incorporating deep verandahs and a central courtyard, with a roof supported on massively oversized, drum-like walls made of locally quarried slate. Boyd said that he felt like he was designing for Robinson Crusoe in designing for the client, Dr Michael Baker, and this simple observation holds a number of clues to the decisions he took in the creation of the house.

The Baker House will remain a living piece of architecture – it is now available for short-term rental, and furnished for entertaining away from the city.

Image: John Gollings

The Baker House is both rustic and self-contained, like a castaway’s dwelling. All things are provided for, including the home-schooling of children, while virtually no luxuries are afforded, despite the size of the house. The schoolroom even contains a ballet practice bar – testament to both Baker’s and Boyd’s desire to nourish the body as well as the mind. And yet, the reference to Crusoe also hints at another fact, at the immediacy of the provision of such comforts: all three structures are generous but discreet in that they provide a certain amount of shelter and amenity, and no more.

At the threshold of the house you get the sense of stepping under a shelter built right over a cleared patch of bare ground. There is no tabula rasa employed here, no plinth conceptually neutralizing the site. The gravel of the ground is level with the weathered slab: you step into, rather than up onto, the floor of the house. The indeterminate nature of the ground emphasizes the delicate ambiguity of the bushland setting, where the horizon itself is denied to the eye by the endless march of the mallee trees.

With this absence of a horizon, Boyd employs the eaves line as a datum against which the vagaries of treeline and the sweep of the enclosing walls read with the passing of daylight. This is something of an inversion of the canonical Modernist move of creating a plinth upon which a structure might stand. With the deep, flattened roof, Boyd gives us a horizontal line against which we can measure our position and our movement, an artificial horizon suspended just above eye-level. This Alice-in-Wonderland-like inversion of the roles of horizon and roof sits comfortably with Boyd’s keen awareness of our antipodean station and of its potential for “otherness”.

The walls of the Baker House’s inner courtyard are festooned with greenery, but the expanse of sky and glimpses of eucalyptus foliage above the roofline evoke the rugged landscape without.

Image: John Gollings

Beneath these generous eaves, the deeply sculptural modulation of light created by the sweeping slate walls is testament to Boyd’s understanding of shadows and light in the Australian landscape. He neutralizes the visual impenetrability of the substantial areas of glazed wall by burying them deep within the shadow of the projecting verandahs, minimizing the bluntness of their reflection of the landscape.

The shelter seems vernacular to the point of being nearly elemental in its contrivance. The detailing of the building is simple and direct, with much effort expended to create little fuss. Simple timber jointing and a straw-lined roof create a sense of rawness in keeping with the rustic nature of the house.

The Dower House is complementary to the main house, by comparison an architectural miniature and an intensely self-contained piece of design. It is the explication of a singular geometrical idea: the figure in plan is a sweeping series of curves that cross a square of enclosure defined by the roof, a gesture of such simplicity and spontaneity that it undoubtedly drew on all of the designer’s skill to execute successfully.

The resulting spaces are eccentric, and yet somehow they contrive to be both practical and entirely livable. Nevertheless, living in the Dower House would demand, of a long-term resident, that rare collaboration of designer’s intent and occupant’s suspension of disbelief – a compromise in the interests of art.

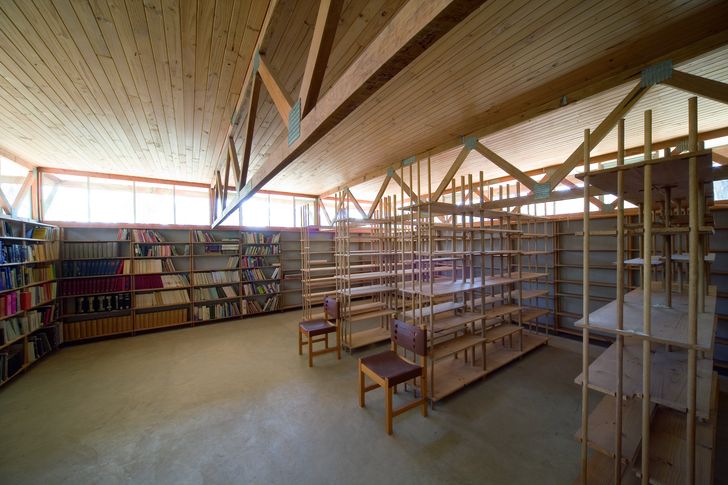

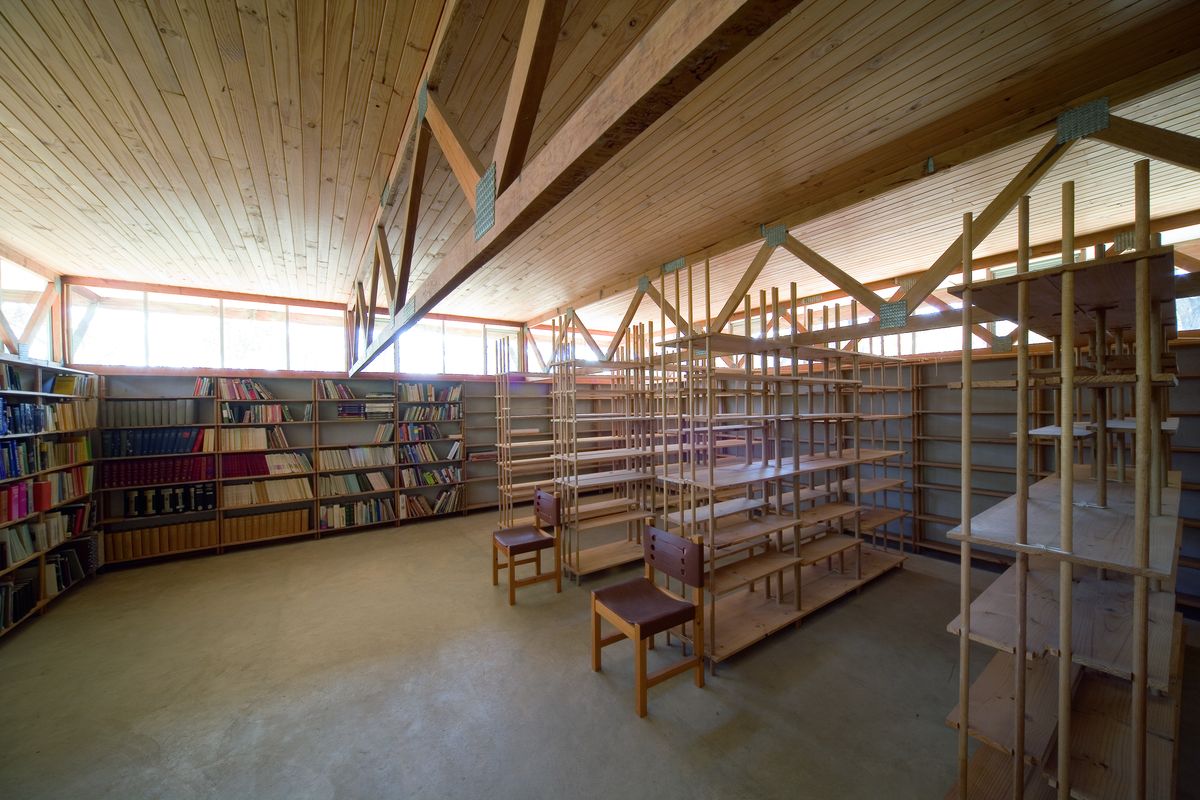

The library/studio was designed by architect Roy Grounds.

Image: John Gollings

The library/studio is different again, and, if you squint your eyes, reminiscent of the National Gallery of Victoria, which was also designed by Roy Grounds. In both projects, a heavy stone wall topped by a strip of glazing supports an overhanging roof, with light entering the internal spaces from high up under the eaves. To an extent, this building lacks the detailed finesse of the Baker House and the Dower House. Nevertheless, it is a tough little building, erected to take the knocks of studio life, positioned on the landscape, in contrast to the two houses, which are positioned in the landscape. The space of the library is serene and evenly lit, and contained Dr Baker’s substantial collection of books, displayed in his ingenious shelfing system which remains. Curiously, the library/studio was intentionally constructed without electricity and remained that way until the current owner took possession.

It is tempting to see the Baker Compound as somehow parallel to, rather than as an extension of, Boyd’s discourse on the Australian city. On first glance it certainly occupies the niche of rustic retreat from the drama of city life – but this appearance is deceptive. Boyd was concerned about the city, the life of the citizen within it and how it could be improved, and his concern for the well-rounded life of the individual pervades this very private work. The Baker Compound can perhaps be understood, figuratively if not spatially, as a city in microcosm. Just as Robinson Crusoe reconstructed civilization in exile, Boyd and Grounds have reconstructed the supports for the many facets of a full life, in the relative isolation of the Bacchus Marsh mallee.

Thankfully, the property has been purchased by a sympathetic patron, and with the enthusiastic participation of Heritage Victoria it will be preserved. It will also be used – befitting its original function as a “living” piece of architecture.

This article appeared in Houses issue 57, published in 2007.