As you enter the enchanting rainforest setting that engulfs Andresen O’Gorman’s Rosebery House, the only evidence that you’re just five kilometres from Brisbane’s city centre is a small glimpse of buildings across the river to the west. This house, in Highgate Hill, is an urban sanctuary – a place to feel calm and grounded within the landscape. Rosebery House was originally built in 1997 for Greg Hooper, Lani Weedon and their two children, Hilde and Angus. It is now home to Greta Burkett, who describes her first encounter with the home as like falling in love. “When I walked onto the property, I fell in love with the gully – it’s beauty made me well up. And [when] we went into the library and saw a glimpse of the river, we imagined that we’d sit and enjoy that view.” The swathe of lush subtropical growth becomes part of your consciousness at every turn, reminding you that you are part of something bigger.

The timber grain of primary posts and beams is reversed to maintain structural integrity, and then visually expressed by its black oiled finish.

The physical form of the house is drawn from the landscape itself and a desire to celebrate and emphasize the topography. “The crease in the land is north–south,” explains architect Brit Andresen, who in 2002 became the first female recipient of the Australian Institute of Architects’ Gold Meal. “The building had to be very narrow to fit on the site. It’s perched along the west-facing ridgeline, just off the stormwater gully floor.” In order to allow for northern light to penetrate deep into the narrow prism, the architect broke the building down into a series of elevated pavilions that require inhabitants to move outside in order to get to the next room. As Brit admits, “It’s a daring thing to do – to force people to move outside to get to another internal space. We made sure to contain the outside areas, so that it was secure.”

Greta explains that the separation of the three pavilions has an impact on the way the inhabitant lives and thinks. “When you are in the kitchen, you are focused on food. And when you move into the bedroom pavilion, you are in the sleeping phase.” The only internal circulation space is the stairwell at the sleeping end, which was contained so that the children didn’t have to go outside during the night.

The home is broken into a series of elevated pavilions, coaxing inhabitants outside in order to move between rooms.

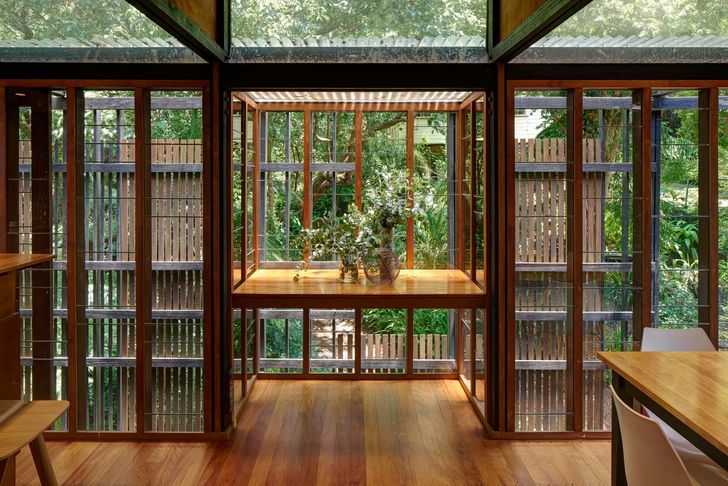

On approaching the home, there is no sense of the domestic scale but rather a reference to the immense scale of the landscape. A twenty-metre-long timber battened screen moderates light, privacy, views and access, but additionally masks the smaller scale of the window frames and balustrades. The varying degrees of transparency along the length of the screen respond to function and shift with the rhythm of the eucalypt battening. Inside the home, everything is broken down into domestic dimensions, with timber studs at 400-millimetre centres within a structural grid of 1,600 millimetres. There is a small gap between the weathersheild (windows) and sunshield (screen), which slightly angles apart to direct your eye toward the view of the Brisbane River. The glazed pavilions are simultaneously open and protected, and the interstitial space between the screen and the house supports fern growth and contains an outdoor shower, private balconies and a kitchen bay window. A spine of books and storage runs along the eastern edge, where the house is attached to the hillside and a narrow clerestory window running along this spine allows glimpses to the sky.

At the same time that the Rosebery House was being designed, Brit’s late husband, architect Peter O’Gorman (1940–2001), was building the Mooloomba House on North Stradbroke Island. This seminal house was an exploration of the expressive capacity of hardwood, and this was continued throughout the design and construction of the Rosebery House.

Bedrooms for the children are accessed via the sole internal staircase, offering protected night-time passage.

Brit, who is Norwegian-born, explained that when missionaries brought Christianity to Norway almost one thousand years ago, the churches were constructed with timber. “Many of these buildings were well designed and aspirational in form, with at least twenty of these buildings remaining today. Maintenance and care over time has sustained the material.” At the Rosebery House, all the hardwood timber frames are expressed and to avoid the warping and twisting of the timber, the grain is reversed for the posts and beams. “You can see the blade in the cut timber, it has texture,” says Brit. “The main frame has been oiled so that it’s black and the secondary structure is left brown.” The regular timber framing creates a rhythm through the entire length of the building, as you move from one space to another, inside or outside. “The timber gives a daily sensory experience. It’s about the touch,” says Greta.

Although the house has a structural rhythm, each of the spaces is specifically tailored to its function. The library or sitting room at the southern end of the home is a quiet zone, sunken down to make it physically and psychologically remote from the rest of the dwelling. The main entry stair leads up to an outdoor entertainment zone, with the kitchen opening onto this deck area. The sleeping area is internally compartmentalized, with a small private balcony and view into the bushland from every bedroom. The lower level contains studio and study spaces, where Lani once worked as a printmaker.

Immersed by subtropical rainforest, this urban sanctuary feels worlds away from the bustle of nearby Brisbane.

The Rosebery House is part of Andresen O’Gorman’s significant contribution to the evolution of the Queenslander house, celebrating and connecting us to our environment through all the senses. This is a highly layered building that intentionally intensifies the experience of the landscape. Being at the home reminds you of your place in the world – you can hear the birds and rain, smell the trees and feel the breezes.

Credits

- Project

- Rosebery House

- Architect

- Brit Andresen, Andresen O’Gorman

- Architect

- Peter O'Gorman, Andresen O’Gorman

- Architect

- Andresen O’Gorman

- Consultants

-

Contractor

Lon Murphy

Structural engineer John Batterham

- Site Details

-

Location

Brisbane,

Qld,

Australia

Site type Suburban

- Project Details

-

Status

Built

Completion date 1997

Category Residential

Type Revisited / first house