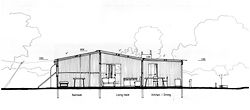

Section of House 36 (Michael Boney). Drawing by Stephanie Smith as part of a study of self-built timber and tin housing at Goodooga.

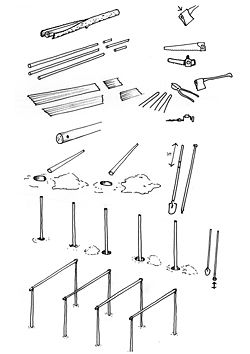

Diagram showing the construction techniques and tools used to make the houses at Goodooga.

House 26. Built by one of Goodooga’s main ethno-architects, Clem Orcher, the house is constructed in two halves – one half can be lived in while the other is remodelled. (It has been rebuilt and redesigned about ten times.) A wide verandah was occupied nearly as much as the interior.

House 36. Built by Clem’s brother for his own family. It also had a bough shade attached that was about the same size as the house. These bough shelters were quickly erected and renewed for family gatherings. Guests often sleep under the bough shade at night when there is not enough room elsewhere.

House 49. Clem’s uncle lived in a single-room house built by Clem across the “flat”. The house had no windows and was quite dark. It was often warmer in winter to sit or lie outside in the sun next to a fire spot out of the breeze. In most households bed frames were often moved from room to room and even outside, depending on climate and household population and dynamics.

House 26. One of the many fire spots carefully placed around the living space. Each fireplace is used for different purposes or at different times of the day or depending on climatic conditions. Different wood is used depending on the heat output required. In this case the hot water for the bathroom is heated in the 44-gallon drum or “donkey” and fed directly into the bath via a piece of water pipe.

The interior of Clem and Isabel’s “living room” was lined with masonite painted sky blue. The floor was a concrete slab flush with the outside and covered with pieces of carpet. A lot of care was taken to keep the room tidy, with the floor swept with a prized stiff broom every day. Elvis music and country and western movies featured strongly in their day-to-day lives and many favourite items are on display. This room is right next to the front door and was occupied as a living and sleeping space depending on the number of inhabitants.

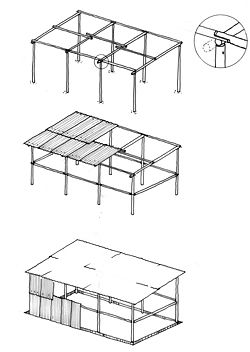

Construction sequence diagram of the self-built houses.

There are two main ways of procuring something. Have someone give it to you or get it yourself. The same is true for the procurement of housing for Aboriginal populations in rural and remote Australia. True also is the adage that “nothing comes for free” – it is the encumbrances of the housing that is “given” that cause the current paradigm of Aboriginal housing “provision” to fail.

Over the past two hundred years or so, Aboriginal people have housed themselves or been housed in a variety of ways. These housing models – whether mission housing, rental, institutional or pastoral – can be divided into two main categories: given or gotten (sic).

Housing solutions that have been “given” tend to involve the imposition of Western-style paradigms of house and community, loss of control and debt. The housing generated by the inhabitants themselves brings choice, flexibility, independence and a sense of pride. Most housing models to date have been deemed by Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal commentators to be outright failures. Most have also fallen into the “given” category. The different impacts of these paradigms are fundamental to understanding the abject failure of government housing policies and the housing they provide.

With obvious problems in the existing Aboriginal housing stock, basic questions need to be asked. Do the funds allocated result in a sustainable solution to an ongoing need? Does importing expertise, labour and materials encourage the development of local industry? Does it encourage education and training that leads to self-sufficiency? When we replace the provision-of-housing paradigm with that of self-built housing, we get very different answers.

Over the years there have been a number of attempts to formalize the process of handing over the management of housing provision to Aboriginal organizations. In general, the management role has been simply one of determining who gets a house, without changing the mechanism by which the house is procured. In only a few cases has it resulted in houses being designed and built by the community using local materials and building techniques. Most of these self-built initiatives have not been further developed simply because they do not fit into the mainstream procurement model.

The current paradigm of housing “provision” to rural and remote communities is fundamentally flawed. Funds meant for housing end up going to transport companies, to urban-based construction companies and to the procurement of expensive and often inappropriate materials. Why do we believe that off-the-shelf house designs will ever really fit the needs of such diverse households in many Aboriginal communities? Do we think that Aboriginal people are not capable of designing and building their own houses? Can a kit building ever be flexible enough to be of any long-term use if the replacement parts are expensive and have to be manufactured in a distant urban centre?

To test the argument that a change in paradigm is needed for the long-term improvement of the Aboriginal housing situation, I undertook a study of contemporary self-built Aboriginal architecture as part of a research Masters degree. The study focused on the internal and external environments of self-constructed timber and tin houses on the Goodooga Fringe settlement in north-western NSW between 1992 and 1996. Goodooga is a remote rural township at the end of the bitumen. The local Aboriginal population came to the fringe settlement near the township in the 1930s with the general forced movement of Aboriginal people from pastoral camps to townships under the auspices of being closer to better education facilities. They brought with them building skills they had developed in the construction of modest dwellings in the camps. These were made from timber poles tied together with fencing wire and clad with opened-out Shell kerosene cans. With the introduction of larger sheets of corrugated iron that could span greater distances, the new structures built in Goodooga required fewer timber members. The dwellings could now also be made larger than the simple, single-room huts on the stations.

Despite their growing complexity and size, these corrugated iron houses were rudimentary and had not been considered worthy of study. They do, however, represent a self-constructed housing paradigm that has many advantages that should not be overlooked in the structuring of housing procurement strategies of the future. Built of local and found materials, they have been derided as an eyesore ever since they appeared in the landscape in the early 1900s. Yes, they are hot in summer, yes, they are hard to keep clean, but they are also free. There is no waiting list for government funding, no rent; they can be built in a few days and modified just as quickly. You plan them how you like and move them when you want to.

In order to validate the findings, dwellings were mapped and remapped over four years. Changes in the configuration of the houses and different uses of spaces during different climatic periods, across diurnal changes and after the influx of visitors were recorded. Spaces between dwellings, orientation and kinship groupings were also monitored.

The study of the houses and households in Goodooga clearly demonstrates a high degree of individual influence in the choice of site, building orientation, plan of the household environment and interior spaces. It is clear that houses and surrounding household environments built by individuals from the community are not only planned differently in response to varying needs, but that each family is different and each house is therefore different.

The tin houses were sited by and built by the occupants or relatives of the occupants. As a result they also represent an Aboriginal vernacular, a chosen pattern of settlement, a map of preferred kinship groups and the ongoing interaction patterns within a community. Each house was associated with a core family group, with the addition of a changing number of extended family members over time. The houses were constantly being extended, rebuilt, modified and used in different ways depending on changing needs. House locations within the settlement reflected kinship relationships and the desire to see what was going on. Even when houses were removed, the sites were still remembered as “belonging” to particular people. Certain family members related to that person were eligible to reoccupy the site over time.

The more recent provision of Western-style housing to the Goodooga fringe settlement has highlighted the fundamental differences between the two housing paradigms. The construction system of brick houses relies on imported materials, is not flexible and hinders changes to the planning configuration over time. The houses are impossible to modify without obtaining additional funding. The cost of delivery necessitates the streamlining of designs and limits individual choice. They cannot be moved. The kinship structure of the community is lost as one family is forcibly evicted and an unrelated person is allowed to occupy the house. People who are not related end up living too close together.

Despite their appearance, the tin houses are a source of pride for their designers and builders. They represent a sense of achievement and independence. They also provide an opportunity for others in the community to learn how to build a house, and against a backdrop of dependency and helplessness, this skill can lead to a sense of liberation. The passing down of knowledge, the pride in building something for oneself or one’s community, the gaining of skills and training, the interaction across generations – these aspects of the self-constructed community are too easily pushed aside for the “easy”, expensive solutions imported from outside. The new “provided” housing may give a sense of pride to the occupants for a while, but it tends to be short-lived. When the full impact of rental arrears, inadequate planning, siting and inflexibility is realized, the houses become a source of stress, and this stress, when repeated within many households, has a cumulative destabilizing effect on the community.

So what to do? The current housing procurement paradigm needs to be changed. It is simply not sustainable nor does it make economic sense to expect rural and remote Aboriginal communities to remain dependent on a centralized housing provision model. Communities need to be offered education and training programs so they can design and build their own houses. To achieve the flexibility and ongoing maintenance potential of the self-constructed housing model, it would be necessary for housing systems not to be dependent on imported techniques, funding and materials. Local resources should be generated and utilized whenever possible.

Participation in the design and construction process by the community should help to foster compatibility between housing typology, planning, orientation and the occupants as well as fostering a sense of pride in the new home. Construction systems using mostly low-skilled labour and locally sourced materials need to be developed.

Independent regional housing consultants familiar with the local and regional construction techniques and materials need to be established. These consultants should act as an advisory service, coordinating community efforts and disseminating information about building systems, training options, grants, etc. A library of building technology, climatic data and building materials available in local regions should be established. Successful local Aboriginal building companies could be used as mentors for other community groups interested in similar initiatives.

While the timber and tin house typology does not represent an acceptable house style for most, if the advantages of the model could be emulated by other typologies the self-constructed housing paradigm could become a more sustainable solution for housing procurement in the future.

Stephanie Smith is a principal of Innovarchi, a design and research-based architectural firm based in Sydney.