Annerley Library.

Sketch of Toowong Library.

Proposed Stones Corner Library.

Centenary Swimming Pool.

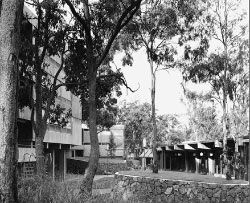

Union College.

J. D. Story Building.

Agriculture and Entomology Building.

James Cook University of North Queensland Library – Stage One.

Maroochy Shire Chambers.

Papua New Guinea Banking Corporation.

Papua New Guinea Development Bank.

Papua New Guinea Arts Law Complex.

Papua New Guinea University Women’s Hall of Residence.

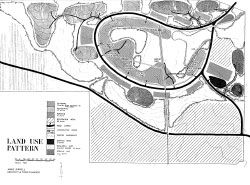

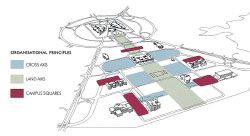

Griffith University Nathan Campus, Brisbane, land use pattern.

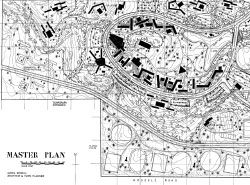

Griffith University Nathan Campus, Brisbane, master plan.

James Cook University, Townsville.

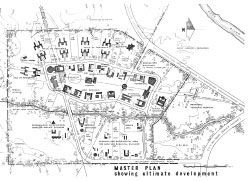

James Cook University, Townsville, master plan showing ultimate development.

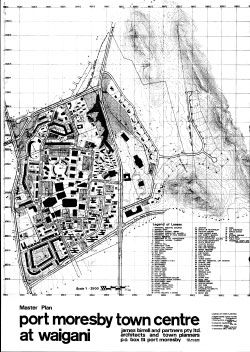

Port Moresby town centre at Waigani, Papua New Guinea, Master Plan.

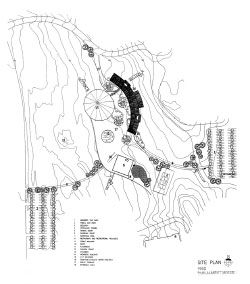

Papua New Guinea Parliament House project.

Site plan.

Parliamentary Zone, Canberra. Courtesy of the National Capital Authority.

IT IS A DECADE and a half since I was in active practice, so I am delighted to find interest developing in my work. The awarding of the RAIA Gold Medal and the listing of Union College have given me the opportunity to revisit my ideas, my buildings and my planning. Also, in accepting the RAIA Gold Medal, after such a long break from practice, I did not realize the difficulty I would have. When searching archives to nominate buildings for the medal events, I found there were almost none that were still intact. Alterations and extensions had been made – often with no sensitivity. In looking back on my career, I now realize that I have never explained myself, particularly in regard to master plans and townscape. So, I would like to use this opportunity to reflect on influences, highlight happenings and explain aspects of my work as well as look to the future for architecture, town planning and landscape.

In 1997 there was a retrospective exhibition of my work at RMIT. A book accompanied the exhibition, BIRRELL, work from the office of James Birrell (NMBW Publications 1997). Already, myths were beginning. For example, I read that Peter McIntyre’s Beulah Hospital and a Robin Boyd house had influenced the Toowong Library. In fact, both McIntyre’s building and Boyd’s were contemporary with Toowong, and not before it. I designed the library, in the tradition of Nero’s Domus Aurea, as one large room contained in a dome with an ocular, for people to enjoy the experience of being together.

There were classical allusions in the designs for many of my projects. (I had visited Hadrian’s Villa at Tivoli, the Renaissance palazzi and the Acropolis at Athens during my 1962 Sisalkraft Scholarship tour.) There are touches of Tivoli in the curvature of the J. D. Story building, while its symmetrical facade was reminiscent of the palazzi with their golden mean proportions, piano nobile, cornice, and varied rough and smooth textures. The Maroochy Shire Chambers has peripteral colonnades and a pronaos two stories in height. Sometimes the historical derivations were more contemporary. The University of Queensland Staff Club has more to do with McKim, Mead and White and H. H. Richardson.

All this seems to have been unintelligible to campus planners and site managers who have since altered them. When will the vicissitudes, fundamental to the design process, be given adequate inclusion in general education – particularly in the education of planners, managers, lawyers, surveyors and bankers? Where is a Cosimo de’ Medici in the ranks of our developers?

However, architecture first.

While growing up in Melbourne and attending Essendon High School, subconsciously, I had been exposed to architecture. At school, games were played at a nearby park where a large incinerator stood, and it made an exciting impression on me. My family would go to the movies at the Capitol Theatre and marvel at the interiors and the lighting. Leonard House, now demolished, was next to the city terminus of the tram I travelled on, and Newman College was a street away from my grandparents’ home. Later at university, through Robin Boyd’s lectures, I became aware that Walter Burley Griffin designed these buildings. Their silhouette, tactility and chiaroscuro stood out.

Griffin continues to fascinate me. In 1964 I wrote a biography on him and this year I will visit the Mayan ruins of Yucatan. Marion Griffin’s two brothers were ranchers in Mexico in the 1890s and discovered pre-Columbian lost cities on their land. Did these inspire Griffin’s work?

But I digress, back to my buildings.

After Hiroshima, in 1945, we were all concerned about the effect of the atomic bomb on buildings – framed steel and concrete remained standing but all applied finishes fell off. I became fascinated with the “as found” finish. Union College, for example, is more about this than clichés of Brutalism. As a worldwide style, Brutalism was, I believe, created for similar reasons, and not as an aesthetic derivation from the English avant-garde.

In September 1955, when I arrived in Brisbane as architect with the Brisbane City Council, the officials at the town hall welcomed me with open arms showing no alarm at my tender age of twenty-seven. The City Hall was very shabby, particularly inside, and a stack of files was placed on my desk containing the backlog of work. The scope was fascinating because the city ran its own electricity generation and distribution, water supply, public transport, library services and swimming pools.

The Queensland chapter of the Royal Australian Institute of Architects held one of their regular meetings soon after my arrival. Government Architect Jim Weller (who had been a student in Walter Burley Griffin’s office and who knew of my interest in Griffin), invited me to attend. All other architects at the meeting shunned me.Weller later explained that the Institute had blackballed the Brisbane City Council. The previous administration of the city had sacked the entire architectural staff with the exception of two bedraggled men, a student and a deaf draftsman. No wonder I had been so readily employed.

The work of my office was broad in the extreme. At the lower end of the scale were many toilet blocks and park shelters (some of which developed from the remains of air raid shelters), works depots, electrical substations, powerhouse extensions, libraries, water treatment plants, sextons’ and grave diggers’ facilities, bus building workshops and transport workers’ canteens. At the other end of the scale was the City Hall itself, which was in an appalling state due to occupation by troops during wartime. Starting with the basement, a women’s restroom was developed from an area used as a military canteen. The press and public were enthralled with the lemon-coloured curtains, Swedish-style wooden furniture, indoor gardens and the awful ceiling concealed in black. The City Hall was refurbished internally, receiving its first paint since 1930; reception rooms were redeveloped and Regency furniture lovingly rebuilt.

The first library I designed was Chermside, in 1956. Built by day-labour over which I had no control, the resulting building was only a shadow of my intention. However, after a showdown, much more faithful interpretations of my work followed, particularly at the Annerley and Toowong Libraries.

The exteriors of the Annerley Library, built in 1957, featured the largest sheets of plywood veneer seen in Brisbane, except for RAAF crash boats and fighter-bombers. Although designed after the Chermside Library, Annerley was finished first and was the first municipal cultural building for Brisbane since 1930. Annerley, today, is overwhelmed by a number of untidy extensions.

Toowong Library has the good fortune of not being altered in form; however, its plywood has been painted, and a space-comic vent has been built on the roof in place of its original transparent ocular. The design of Toowong Library, which was officially opened in 1961 with over one thousand people crowded in the street outside, has caused continuous press controversy. Journalists decided that, as the site had been used as a works depot for many years, the circular forms of the lower floor were hiding a sewage pumping station.

With acceptance from the public and the confidence that the Toowong Library’s design gave me, I did one more library scheme. It was to replace the Stones Corner library and I still feel that this was my best design, although it was never built.

Nineteen fifty-nine was the centenary year of both Brisbane City and the State of Queensland. The city celebrated by building the Centenary Pool Complex (1957–59).

Leaving the Brisbane City Council, in July 1961, I reported for duty at the University of Queensland, where history seemed to repeat itself. My new office was not much more than a cleaner’s cupboard with two desks. Other than a secretary, I had no staff. I was chief executive officer of the Senate Committee for Buildings and Grounds, coordinator of architects commissioned for projects required by the University, liaison officer with the Australian Universities Commission, and architect for a new administration building and for some minor works. But all my architectural work was held up indefinitely by negotiations between governments and the university, and while professors fought each other for priority and prestige.

A new commission saved the staff I had built up. It came from the Council of Union College and it was to design a new residential college on the St Lucia campus. Union College, although affiliated with the university, was an independent body. They had been granted a site at the lowest point of the campus behind industrial buildings in the engineering precinct. It was dreadful with drainage problems and crisscrossed with services. I successfully suggested a better site known as “The Tree Reserve” on the edge of the campus. (“Reserve” was, in fact, a misnomer as all the trees were regrowth over old farm pasture.) By weaving the building form across the site, Union College avoided the more substantial trees, and the result has been acclaimed.

In 1961, I had been awarded the Sisalkraft Research Scholarship in Architecture and soon after went on my first grand tour. In Milan I had found a most sophisticated window system. It was double-glazed with adjustable venetian blinds between the sheets of glass. I incorporated these into the designs for both Union College (1964–70) and the J D Story Building (1964–65). All the windows for Union College were imported from the United States and, in recent times, the college council replaced them, the hinges having worn after thirty years. But the council would not pay the patent rights on new hinges, instead replacing the large panes with several small windows, thus destroying the scale of the building – and just before it was heritage listed.

The imported windows upset local manufacturers of aluminium products who petitioned the government which responded by refusing to allow any aluminium on a building receiving State funding or subsidy, where the product was not sourced from ingot produced in Queensland. So, on the J D Story Building I had to settle for a rough copy.

My fascination with “as found” finishes is seen in Union College. Sir Albert Axon, chancellor of the University of Queensland, laid the foundation stone and by the time of the ceremony enough construction had taken place to see the nature of the off-form concrete spandrel walls and the clinker brick cross walls. Axon let the assembled people know his distaste for these “as found” finishes. I thought the bricks were beautiful, being clinker in deep ceramic blue and brown, not unlike some Japanese or Milton Moon pottery, and they had an enormous crushing strength allowing the building structure to go six stories in four and a half inch brickwork. The result was that the completed stage one cost was less than half the priceper- bed of other residential colleges throughout Australia.

I laid out Queensland University’s Agriculture and Entomology building (circa 1969) to step down the contours of the site one floor at a time in three wings, so they formed a U-shape enclosing a rolling lawn with established trees in the foreground. This was not unlike the principle behind the site layout of Union College and these became precedents for buildings in my master plan for Griffith University.

When selecting bricks for Agriculture I had noticed an enormous pile of rejects. I inquired about them to be told they were seconds and no one wanted them. I thought they were quite beautiful, having an ochre colour with speckled spots of red caused by iron ore particles pickled in the surface during firing. Also there were many burn marks on the bricks where they had touched iron wrappings. As seconds they were very cheap, and they were very strong. My proposal to use these was put to the Senate, alarming the chancellor. I was asked to reconsider. I pointed out that the bricks’ appearance was the result of a manufacturing process – very contemporary and beautiful. I requested a meeting of senators on site to illustrate this. The colour was not unlike the sandstone in the original university buildings when seen from the main frontage of the university. I explained that I liked the bricks because they had the aesthetic of Jackson Pollock’s painting “Blue Poles”, recently purchased by the National Gallery of Australia. This comment, and the price, did the trick.

The University of Queensland established its Townsville campus, the University College of Townsville in the early 60s (later to become the James Cook University) and I was asked to prepare the master plan. The Townsville University Library (1966) was to be the focus of the entire campus. It was centrally placed at the junction of the generating axes of the master plan. The building was conceived as a three-storey rectangle of off-form concrete with a great overhanging roof. The lowest level was open as a central shaded undercroft where all the university population could meet and relax. The concrete walls of the exterior sloped slightly as they rose, and at the level of this meeting place they were pierced with circular windows, which were random in size and location. This added to the atmosphere of relaxation. I felt this important as a counterpoint to the intensity of study and research. Too few of the universities in Australia had any specific spaces allocated for students to relax and talk, other than in refectories, or corridors.

In 1966 I left the University of Queensland to commence private practice. Commissions came from the State Department of Works to design some of the buildings at the Darling Downs Institute of Higher Education at Toowoomba, later the University of Southern Queensland. Sir John Gunther, the first vice chancellor of the University of Papua New Guinea, also contacted me requesting I visit Port Moresby with a view to designing some of the buildings the university would require. This resulted in commissions for the arts complex, staff housing and two halls of residence. Soon work came in at a rapid rate. Included were the Commonwealth Bank of Australia (soon to become the Papua New Guinea Banking Corporation), town plans for the new capital at Waigani, old Port Moresby and Madang and the master plan for the University of Technology at Lae. The private sector also supported me.

Papua New Guinea has listed many of my buildings and they remain intact. The building of the Papua New Guinea Development Bank headquarters (circa 1973) was the first exciting project in another country. It gave me the chance to illustrate how the master plan for the capital city area could be used to advantage architectural design and avoid rigid orientation. The building was oriented north-east / south-west, with sun control by diagonally set windows creating shadows that enliven the building. It was also the first public building in that country to integrate indigenous art into the design.

The headquarters of the Papua New Guinea Banking Corporation (circa 1975) was built in the centre of the old city of Port Moresby. Here, indigenous artists had a great time designing base relief patterns for all the exterior columns. The method was a development of the system I had used years before in Brisbane at the Wickham Terrace Car Park (1958–61).

The first arts/law building at the University of Papua New Guinea (circa 1968–72) gave an opportunity to develop my ideas regarding the use of pre-cast eyelids over windows for sun control. As it was the first building I was concerned with so close to the equator, I studied as much architectural precedent as I could find, where there were similar climates. One building stood out. It was at Pondicherry and was designed by Anton Ramón. He had protected the roof from the intake of heat by shading it with a canopy of curved concrete shells. I had seen the same idea in the Mogul architecture and Lutyen’s work at Delhi, where the canopies were stone with free air movement beneath. My project could not afford either of these materials; however, I obtained the same effect by using curved corrugated galvanized iron water tank forms.

Moving on to planning.

For some decades I have realized that my planning work on towns throughout Queensland and Papua New Guinea, and for several university campuses, has been misinterpreted, forgotten or abandoned. To revisit these now, and to explain myself in regard to master plans and townscape, is very opportune, and at a time when planning, itself, is in danger of losing its strength as a design discipline.

Several years ago, the Department of Town Planning at the University of Queensland was taken from its association with architecture to be partnered with the Department of Geography, where it is overwhelmed by statisticians and geographers. The planning concepts by which I had passed my examinations in 1959 had changed. The principles of Patrick Geddes or Doxiadis’ Ekistics, wherein accurate studies of existing conditions and history were basic to town plans, are no longer a focus. Urban design has become a matter of planners setting infrastructure and density conditions, financial contributions, and protecting the interests of councillors or ministries. Appeal is to “blind” courts of law.

The planning profession is no longer a territory in which the people doing it have skills in manipulating space. Of course, the social scientist brings invaluable skills, but these seem to be moving the profession too far from its architectural and townscape roots. Paul Hyett, a recent president of the Royal Institute of British Architects, comments “You can’t take a geography student who’s done a planning course and turn him into an urban designer. You have a better chance of turning a furniture designer into a master planner.” ››

Planning can lead to wonderful results when planners appreciate the aesthetics of design as they practise development control. Often the difficulties arise when one takes a sophisticated design to a planning officer who has limited training in design, yet is empowered to affect it.

In the 50s, San Francisco’s elected authorities appointed advisory panels of eminent designers, for example W.W. Wurster, to report upon applications so that they had available independent and significant advice, not just the opinions of their officials. The Dutch have a similar process of review. The RAIA could play a role in establishing such a system here.

In 1963 the University of Queensland had commissioned me to prepare a master plan for its university campus at Townsville. All these university planning commissions allowed me to develop ideas that went back to Griffin’s planning of Canberra – the arrangement of all building groups set into the broad landscape focused by generating axial lines and as mini campuses to avoid back and side elevations.

Generating lines for the plan at Townsville were focused on the escarpment of Mount Stuart, the centreline of the amphitheatre of mountains in which the site sits, and down the campus towards the city and Magnetic Island. The early buildings of the campus (Humanities, the First Hall of Residence and the Library) respected this. Vistas from the courtyards of the Humanities complex, the First Hall of Residence and the Main Library, embrace Mount Stuart and the broad mountain silhouette. Drawing this great escarpment into the campus reminds me of the streetscapes of the old parts of Edinburgh, which are often closed by great bluffs. Nowadays, new buildings on the James Cook campus are in the good old regimented grid, and the generating lines into the landscape disappeared from the plan about 1968.

Around 1964, I was commissioned to prepare a master plan for what became the Griffith University campus at Nathan in Brisbane. The site was large and beautiful and almost untouched by human occupation. It was the head of a stream catchment – a hidden valley inside the crown of a hill. Because the vegetation was spectacular, I commissioned Professor R. L. Specht, a botanist, to report on the botanical aspects of the forest. This resulted in the discovery of eucalypts peculiar to the site, as well as the identification of all plants, particularly ground cover and shrubs.

The plan consisted of a ring road circling the ridge of the catchment. I located the university’s academic core within the ring road while the residential colleges and sporting facilities were to be outside the road. The buildings were based on the principles established at Union College and Agriculture and Entomology, enabling the building forms to weave around the significant trees. The academic buildings penetrated into the valley in fingers of related disciplines. Little vehicular traffic was to be allowed into the academic area, with parking accommodated outside the ring road. Pedestrian movement throughout the natural flora carpet was to avoid disturbance of the ground cover.

When Griffith University was established, they did not continue with my services. Nevertheless, subsequent site planners respected the land use pattern I had established and continued with the preservation of the vegetation. However, they abandoned the concept of weaving buildings through the flora, instead imposing a rigid rectangular grid with east-west long axes and north-south short ones. This is an anathema to me and continues across Australia. Eventually, when everything from detention camps to university campuses to downtowns meet, they will all interlock neatly, like children’s Lego. Unless site planners study the layout of the Acropolis, with its buildings subtly out of alignment to any grid, no buildings can be accommodated in the style of Aalto, Gehry or Burgess.

Also in 1963, the Interim Council of the University of Papua New Guinea had arranged for me to be seconded from Queensland University for several weeks to assist in the selection of a site and preparation of a master plan. Geoffrey Harrison of Adelaide was also seconded. A joint report resulted in the selection of the site and the master plan for the university.

The master plan for old Port Moresby redevelopment was based on site coverage, height controls, and boundary setbacks above the third floor, with arcading and colonnading at ground level. Gross floor space indexes and footprints were less than the envelope; architects had to design the buildings within the envelope but not to it. Normal town plans of the time, such as the Stockholm plan and the National Capital Development Commission plan for Canberra, particularly around Civic, insisted on exactly matching the envelope to the site coverage, floor space and side boundary clearances. This left the architect merely fiddling with facade details. There is no silhouette or tactility. The result is boring.

Still in Papua New Guinea, the plan for the new capital at Waigani gave me the chance to develop my idea of each group of buildings being arranged around a mini campus. Instead of the primary design consideration of street frontages focused upon motor traffic with the rear of allotments becoming back yards, integrated pedestrian courts behind the buildings would develop. This system of mini campuses within a major campus reappears in many of my master plans and in the review that I chaired recently of Canberra’s Parliamentary Triangle.

Planning does not endear the planner to architects, engineers, surveyors and developers, particularly when they have had no constraint on their work. Nor does planning endear the planner to the environment lobby unless one joins them, to the detriment of a comprehensive approach to the integration of architecture, town planning and landscape.

Architecture is a continuum of civilization, not just trends of fashion. Townscape has tactility and silhouette, and is not the result of development control or legislative procedures and codes. In fact, it can be destroyed by these.

Presently, decisions for posterity are being made through development control, arrogant bureaucracy and blind justice. Most of our contemporary architecture is not part of street life, although there are many talented architects. Australia’s townscapes were stillborn after Briggs was sent to arrest the influence of Macquarie, our first great patron of architecture and townscape. There is so much investment, yet it rarely reflects in distinctive townscape.

Recent amendments to South East Queensland planning schemes have been made for good reason – to intensify housing in older suburbs where urban renewal is encouraged and to save infrastructure and transport costs. The consequences to townscape have been less than desirable in many places of historical significance.

An example is the Brisbane City Council Code for small lots, which promotes the ever narrowing of side boundary clearance, and the code management of privacy, which truncates eaves and blinds fenestration with slats. Surely, if units within a lot can have common walls, why can’t small lots have zero side boundary clearances allowing a return to the Roman concept of cortile plans? As town plan codes constrain development to land with slopes of less than fifteen percent, will we ever have superb towns like Sorrento on the Amalfi coast? Will we be able to attract architects to emulate J Horbury Hunt’s hilltop convent at Rose Bay, Sydney, or the cliff hugging house of Peter Johnson at Chatswood?

I believe the “Tuscan” misnomer was spawned as up-market housing estates result in homes set in almost gated suburbs. There is no high street, only a supermarket and a car park. Maybe all development control officers should study a little town history, and do a grand tour of the Mediterranean and Ming China. The home buyers have no say. Gone is the postwar vision set by Boyd and others with The Age Small Home Service, which gave so many young architects their start and homemakers their choice. Today, speculative developers work to brokers’ advice and project managers control design parameters. By the time the end owner is involved, everything down to lawns, shrubs and street furniture has been established.

So, how might we achieve architecture that makes a strong contribution to our environments?

The extension of the Finnish Embassy in Canberra is outstanding in its architecture and its integration with its environment. The architects were selected in Finland by competition, as happens for all public architecture there.

Overseas, the competitions are held to select architects and their designs. Here, it seems to be how well the selectors get on with, or like, the architect. The decision seems influenced by managers, academics and committees who wish to continue to affect the project rather than let the architect develop their concept.

Compare the Finnish competitions with some in Australia where there is no public exhibition of entries and, although nominated in the original brief, judges of significant international and independent stature are absent from the jury, for whatever reason. Not only does this shift the goal posts, but also posterity is denied the cross section of ideas of our time. In the past, a competition was a celebration of the efforts of entrants, with exhibitions and publication of the submitted works becoming a time capsule of designers’ philosophies. The competition system should be revisited by the RAIA.

Iconic architecture does not happen out of daily fashions.We are lucky to have Utzon’s opera house. Egypt got its pyramids over a millennium or two, and the Greeks got the Acropolis in half a millennium. The Romans with their domes, and the Goths with their cathedrals, did it in a third of a millennium. Foster, Gehry and Libeskind follow Corbusier, Wright and Kahn, as they seek to establish new icons in a decade or less. In time, some good architecture will burn into our civilization’s consciousness.

My more immediate fear, while all this is happening, is the loss of vernacular architecture. Never before has the local environment, in which people live every day, lost its way, yet never before has so much been at our command to provide beautiful towns.

Architecture faculties have lost some of their dignity in husbanding the arts as they are shunted into lesser disciplines of environmental science, surveying, geography, management, and whatever else. They need significant funding to raise their presence. They should be led by prominent practitioners with proven bodies of fine design. The relationship between the university training of architects and the practising profession should be seamless.

The Germans were doing this when I visited them on my Sisalkraft tour back in 1962. A major architect in practice was offered a chair for a few years and the practice was supported with supplementary staff provided by the government if the offer was accepted. If the offer was not accepted, the practice could not expect much further official support!

As building design drafters and certifiers can now produce all documentation for approvals, it is becoming rarer to see an architect’s name on projects large or small. The lowered bar has tarnished reputations. Architecture is the sum of many fundamentals – cultural, economic, technical, and even poetic. If an architect builds something that fails, it is usually a little more serious than a mistake in grammar. The compromise reached with building designers, to satisfy political correctness regarding deregulation, does not recognize that everyone employing the services of a professional knows the difference. It seems everyone has the right to build a modern building and affect the environment. If everyone is an architect, maybe no one is.

The British have just begun to acknowledge the problem, renaming their relevant ministry Architecture and the Built Environment. Australian governments may one day have ministers for architecture and townscape. After more than a half-century since their demise, should we be grateful for recent appointments of a few part-time government architects?

While the RAIA has conferred honours to those whose service deserves them, they do not distinguish, in the public eye, those who have gained these honours through their repertoire of design. Something like a royal academy added to membership titles may help, particularly if major clients, such as governments, and judging panels are encouraged to note these. The Japanese do this, with a very limited number of architects given the status of national treasures. Only when one passes on can another be elected. The Institute has its awards to help. However, so many are issued in each region each year, now, rather than the original system of one meritorious award and a few commendations. It seems that, if one invents a new category, one wins the prize for it. The public yawns.

Gregory Burgess, in last year’s A. S. Hook address, stated, “If architecture is to be more than visual composition … for the bored elite, we need to re-engage with society. As architects our buildings should do the talking.” His allusions to Tim Winton lie comfortably with the Australian vernacular – not the elite vernacular of the specialists in tin and timber with reclusive exclusion of the popular. Rather, we need the matrix from which home-grown townscapes will grow. People, in droves, buy things at Bunnings to embellish their homes and these things are not necessarily Swedish. One can imagine an urban texture pervading our townscapes with silhouette and tactility, and this awakens in Corrigan’s RMIT elevations in Swanston Street.

Post-modernism has developed with the tyranny of computer graphics and binary logic creating a post-historical, post-literary culture. The results in architecture are disappointing. Charles Jencks, in his promotion of post-modernism, intentionally misunderstood Le Corbusier as the origin of minimalism. He ignores the content of Towards a New Architecture, 1923, where Le Corbusier analyses many historical architectural monuments in search of universal truths in aesthetics, such as scale, proportion, harmony, and then relates these icons to contemporary phenomenon – liners, aeroplanes, and automobiles. Jencks now admits architecture has become “an assemblage of clichés rather than a resonant symbolic architecture.” ›› The Modernists understood what they were reacting to. They had been satiated with history involving 500 years of ever more dumb aping of Palladio’s classicism, tired Gothic Revival and Liverpudlian good manners. They did not ignore the continuum of proportion and geometry descended from the ancients.

We should all learn to look backwards and forwards simultaneously, as John Olsen did this year in his Archibald self-portrait.

Since the 60s, minimalism, post-minimalism, post-modernism, deconstructivism, poststructuralism, and contextualism take centre stage, one after another, often lasting less than a decade. Some started close to hip then descended to kitsch.

I do not subscribe to a denial of virtual reality or information technology, as these are now the matrix that was paper and canvas fifty years ago. These are the medium not the content. Until this is understood, globalization and homogeny remove much of the spontaneity of regional architecture.

The two-dimensional photographic image in brochures, magazines, and on television, rather than the physical embodiment, is more often the reality. A culture of illusion engulfs our built environment and the public yawns, again.

Taking all this on board and “with the bottoms of my trousers rolled”, I am here as an elderly “spy who has come in from the cold” rather than, I hope, as a derelict at his retrospective.

Silhouette, tactility, chiaroscuro!

JAMES BIRRELL IS THE RAIA GOLD MEDALLIST FOR 2005. THIS IS AN EDITED TRANSCRIPT OF HIS A. S. HOOK ADDRESS DELIVERED AT THE BRISBANE CONVENTION AND EXHIBITION CENTRE ON MONDAY 24 OCTOBER 2005.