Since the 1970s, Australian cities have wrestled with their identities, questioning where their centre – or heart – lies. Is that heart best understood in the concentrated, capital city CBDs, or in the sprawling suburbs that make up the majority of their area? Does it reside in its colonial occupation or in the waves of twentieth-century migrants that have followed since?

As a suburb 22 kilometres south-east of central Melbourne, Springvale represents a highly distributed form of city, in both its physical form and its social makeup. It is one of the most ethnically diverse places in Australia, with a huge percentage of its population coming from various countries in South East Asia.1 This is not by accident. The Enterprise Migrant Hostel opened there at the end of 1969, offering accommodation and settlement services to migrants and refugees. Between 1970 and 1992, the hostel housed more than 30,000 arrivals, with large numbers coming from Vietnam and Cambodia to escape the strife there. People stayed in the area after passing through the hostel, building the communities that are evident today. Although the White Australia policy had only recently been dismantled in law, the council welcomed the newcomers. Local temples were built and the shopping strips central to Springvale began to emerge.

The suburbs enjoyed a few high points during the 1970s. On the night of 2 December 1972, after being elected prime minister, Gough Whitlam held a press conference from the living room of his home – a relatively modest suburban house in the western suburbs of Sydney designed by a Cronulla architect. The Whitlam Labor government represented a moment of intense interest in shaping cities by policy and in strategies for decentralization while, internationally, planners were proposing satellite towns as a solution to the rapid urban growth of the baby boom. Yet the momentum of this expansion policy was brief; economic crises and emerging deregulation set off the contraction of the manufacturing sector, which had stimulated growth in urban peripheries. Globalization had begun to pressure factories and the same logic preferred cities shaped by the free market over government planning. As early as 1981, Melbourne planning strategies were turning away from satellite growth and toward reconsolidation.

Outside, multipurpose courts, playscapes and gardens invite community engagement.

Image: John Gollings

Ever since, places like Springvale have been caught in a kind of metropolitan crossfire, with one architect after another deriding their presence, muddling aesthetic preference with the ethics of how and where to live. Such suburbs are strewn with design efforts that set the value of the suburban below that of the centre. However, the new Springvale Community Hub by Lyons flips that value and, rather than muddling the debate, gives it several sides. This is architecture that both challenges and responds to complex questions of identity.

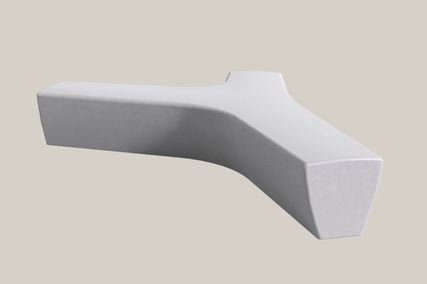

Traditionally, public buildings have backs and fronts; modernist objects usually assert their singularity. In contrast, the Community Hub is an object with four distinct and deliberately articulated faces. One concave side inflects and reflects around some beautiful river red gums, taking its cues from the timber. Another side, facing Springvale Road in stacked glazed bricks, is a striped and waving flag, designed for a new, culturally diverse nation yet to be invented.

With no single face, the building perhaps reflects the complexity of the migrant experience.

Image: John Gollings

The opposite facade – with its huge red eaves and triple-brick courses – reflects suburban backyard environments in a giant version of the adjacent houses set behind fences. Facing the entry car park, this side becomes an infrastructural buffer, learning its language from the asphalt ground marked by lines and cats’ eyes. At moments, these faces meet suddenly. Spliced together at corners, they are theatrically fragmented – less a collision, more a precise propping against each other. This is a building with more than one face – just like the migrant experience.

These four faces become even more evident because this is an object in the round, within suburban space. Without a trace of New Urbanism street edges, there’s an embrace of big setbacks and car-park forecourts. The library almost swaps the figure-ground with buildings it replaced nearer the street; it is at the centre of a civic garden now and the landscape does plenty of the urban work. A casual seating axis connects the street to the building corner, and large, open gardens replacing buildings have revealed new views of the refurbished red-brick City Hall, the former home of the Springvale city council proclaimed in 1961. As I wandered through this stretched space, I passed numerous games of basketball, two barbecues in action and schoolkids singing happy birthday under bright orange umbrellas. Above it all, on the wall’s giant screen, COVID-19 health messages were being delivered in Vietnamese. A new rose variety – “Enterprise” – grows in the forecourt’s Spirit of Enterprise garden – a memory of the well-cultivated rose garden at the Enterprise Migrant Hostel.

The interior of the customer service hall is inspired by the Enterprise Rose, which grows in the forecourt’s Spirit of Enterprise garden in memory of the Enterprise Migrant Hostel. Artwork: Material Thinking

Image: John Gollings

The Community Hub’s interior is expansive and sprawls over two levels. Three holes cut vertically form informal halls and voids, echoing the trees. This circular geometry runs counter to the linear geometry above, with its sawtooth roof lights, but both serve to open the space in each direction and distribute a very even daylight. The concave court around the river red gums is present in much of the interior and filters more light through its double screen. There are so many materials, so many surfaces – pockets of variegated space are formed everywhere, for different ages and different languages. But just as the architectural language starts to dissolve, it is brought back under Lyons’s umbrella idea: that more is better.2 Pieces within the space are chunky and robust – such as the fat timber rail wrapping around the voids. This is a building putting down roots, not touching the earth lightly.

Community hubs like this are great social condensers and Lyons’s building does all the right things to deliver an excellent facility that also demonstrates best practice environmentally. Beyond this, though, the architecture’s dexterity and agility gives expression to a city with a complicated identity. The travel restrictions of 2020, when Melburnians were constrained to within a five-kilometre radius of their homes during the pandemic-induced lockdown, amplified the uneven privilege across the metropolis. Suburbs such as Springvale are still often perceived as “sub.” So, the consideration given to Springvale by this architectural work feels even more significant. This complicated city remains slightly unsure of its identity – but it continues to seek its own language. Compositionally, the Springvale Community Hub is saying, “The world is just like this. But could it also be like that? Or like something else?” Given that most of us (being non-Indigenous) are migrants, these questions are worth examining.

1. According to the Australian Bureau of Statistics, the most common ancestries in Springvale in 2016 were Vietnamese (21.2%), Chinese (17.5%), Indian (6.7%), English (6.5%) and Australian (5.1%), quickstats.censusdata.abs.gov.au/census_services/getproduct/census/2016/quickstat/SSC22317 (accessed 24 March 2021).

2. Lyons, Juliana Engberg, Paul Carter, John Macarthur, Leon van Schaik, More: The Architecture of Lyons (Melbourne: Thames and Hudson, 2012).

Credits

- Project

- Springvale Community Hub

- Architect

- Lyons Architecture

Melbourne, Vic, Australia

- Consultants

-

Accessibility consultant

Architecture and Access

Builder Ireland Brown Constructions

Client Client City of Greater Dandenong

Landscape architect Rush\Wright Associates

Planting Paul Thompson

Public art Material Thinking

Quantity surveyor Currie and Brown

Services, sustainability and AV engineer AECOM

Structural, civil and facade engineer Meinhardt Bonacci

Wayfinding Fabio Ongarato Design

- Aboriginal Nation

- Springvale Community Hub was built on the land of the Bunurong people of the Kulin nation.

- Site Details

-

Location

Melbourne,

Vic,

Australia

Site type Suburban

- Project Details

-

Status

Built

Completion date 2020

Category Public / cultural

Type Community centres

Source

Project

Published online: 3 Aug 2021

Words:

Graham Crist

Images:

John Gollings

Issue

Architecture Australia, July 2021