On occasion, an architect is able to work iteratively over an extended period in such a way that their architecture comes to define the character of a place. We are thinking of Jože Plečnik by the river in Ljubljana, Slovenia, Luigi Snozzi’s seven rules for the village of Monte Carasso, Switzerland, Fumihiko Maki’s work over fifty years at Hillside Terrace, Tokyo or, more recently, Gion A. Caminada’s tactical rejuvenation at Vrin, Switzerland.

To the above list, we would add Richards and Spence’s James Street precinct in Brisbane’s Fortitude Valley. Since 2012, the architects have been working with brick, concrete and stone to develop an alternative vernacular to the traditional use of timber and tin.

This way of making is also a form of resistance to the otherwise rapid cycle of contemporary city-making. It seeks longevity and the embodiment of knowledge within material things.

Walking the precinct, the words of Adolf Loos in On Thrift (1924) come to mind: “Luxury is a very necessary thing … Every attempt to reduce the lifespan of an object is a mistake. On the contrary, we must raise the lifespan of the things we produce.”

Poolside cabanas and the curved balconies of the hotel rooms above engage guests as both spectacle and spectator.

Image: Sean Fennessy

Within this context, the focus of our gaze is the Calile Hotel, the latest and largest of the eight projects by Richards and Spence in the precinct. It is an L-shaped perimeter block form rising to six storeys above a two-storey podium. The building completes the eastern end of the city block that defines the emerging character of the James Street precinct. The podium has three frontages to public streets, while the fourth activates the recently completed through-site link known as Ada Lane.

In publication, the project is often referred to as an urban resort. This nomenclature gives us pause – if the essence of urbanity is proximity and inclusivity, the term “resort” implies exclusivity. In recent times, this conflict has resulted in simulacra public spaces crafted in service to vested interest, that effectively disenfranchise those without capital. It is evident

the architects have recognized this conflict and worked within the limits of their role to engender civic-mindedness. This is apparent in the generosity of the materials, detailing and planting of the street interface, the prominent clocktower, the cruciform porosity of the podium and the grandeur of the stair to the pool deck.

From the street

Arrival at the hotel lobby is facilitated either via the low porte-cochère or the wonderful lofty and sculptural arcade off James Street. Entering the hotel in that manner, beneath the improbably levitating concrete awning and the heft of the 710-millimetre-thick arch in white brick, the space lifts and squeezes.

A small balcony clad in travertine – for plants, not people – is momentarily overhead, imperceptible. There is daylight above and far beyond, sliding across and extinguishing itself quickly on the rough-formworked concrete soffit. The slow arc of the day spa above, again in travertine, gives space and is punctuated with fine-framed glass boxes. Below, at the height of a person, the shop frontage turns the corner from the street and into the space.

As a whole, it is a magnificent plastic composition reminiscent of the back side of Le Corbusier’s Ronchamp, or something Enric Miralles might have concocted. More locally, though no less significant, the conflation of interior and exterior building elements evokes the manner of Donovan Hill.

A small building within a large building

Later, by the pool, we sit within one of the seven cabanas, the roof a mass slab of concrete. Within, the form is indented deeply so the circumference described by the slow revolution of the black ceiling fan holds a concentric shadow. The curtains either side are white, light, and the material weave open. The white brick columns are scaled to the mass of the roof in the manner of other classical structures. At the rear is a terracotta screen and, beyond, the veiled city. A low chaise in green fabric with a fine white steel frame furnishes the structure. Air moves freely.

Two private rooftop terraces are accessed from the hotel’s primary suites and overlook James Street.

Image: Sean Fennessy

Within our small temple, we are apart from but remain a part of the theatre of the pool. We talk about the way in which these structures negotiate privacy and voyeurism, how we are both spectacle and spectator. From our vantage, the distinct curving balconies of the rooms above bring to mind first the Standard Hotel in West Hollywood, but then also the story Rafael Moneo tells of his wonderful elliptical-fronted apartments in San Sebastián and how they allow views not simply out but also directly up and down the boulevard. The theatre of the pool transforms this latency, which further charges the experience.

Consideration of a room

It begins with the door, which is accessed via the open-air corridor and located within a small alcove shared with the room next door. This widening of the corridor is space that would otherwise be for the generosity of the room, but here it is given to the shared entry. Already, and within the extreme codification that governs hotel design, we perceive a shifting of priorities.

Beyond the threshold, there is richness in the detail of the room’s making – the arch, the window seat, the sliding screens and vanity, the ingenuity of the interlocking ensuite doorhandle. We have become so used to the profusion of travertine lining the walls and floors of the public areas that the subtle transition to cork surprises. The use of this material is an inspired design decision informed by economy, material memory, chromatic warmth, tactility and acoustic attenuation.

Inside the hotel rooms, archways repeat the geometry of the scallop-shaped balconies. The cork on the floor and lower wall is a surprising contrast to the travertine of the public areas.

Image: Sean Fennessy

The lamps

Within the room, there is a lamp beside the bed. It is not so consequential within the overall accomplishment; but, for some reason, it stays with us. This lamp seems to distil the generosity

of the building. It is a brass sheet in the shape of the arch within the room, folded in half tostand upright and so perceived as a semicircle. Filling one half of the vertical face of the semicircle is an Artemide Dioscuri diffuser. That is it. The design can be written via a geometric order and bricolage.

In itself, the object has an integral beauty. It serves the pragmatic purpose expected, giving

light directly and reflecting it off the brass surface. It conceals the power point mounted high in the wall beyond. It evokes other materials and forms, giving a cohesion at the level of the room, the building and the precinct. However, it is not until the end of the evening that we realize the asymmetry of the fitting is as much about the placement of the light source as it is the making of an adjacent absence. This folded surface remains empty until we seek to find a place for the collected detritus of our day – wallet, keys, phone.

It is a small gesture, but the beauty of experience is built by small gestures.

Credits

- Project

- The Calile Hotel

- Architect

- Richards & Spence

Fortitude Valley, Brisbane, Qld, Australia

- Consultants

-

Access consultant

Indesign Access

Audiovisual consultant Soho Sound Design

Bar and gymnasium fitout Lamberts

Builder Hutchinson Builders

Certification consultant Knisco Development Solutions

Civil and structural engineer ADG Engineers

Electrical engineer SDF Electrical

Fire engineer and services consultant Omnii, Citi Fire Services

Hydraulic engineer H Design

Landscape consultant Lat27, Botanical Grace

Mechanical engineer VAE Group

Project manager Blades Project Services

Signage designer Studio Bland

Traffic engineer TTM Consulting

- Site Details

-

Location

Fortitude Valley,

Brisbane,

Qld,

Australia

Site type Urban

- Project Details

-

Status

Built

Completion date 2018

Category Hospitality

Type Hotels / accommodation

Source

Project

Published online: 13 Sep 2019

Words:

Andrew Scott,

Anita Panov

Images:

Sean Fennessy

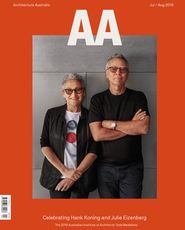

Issue

Architecture Australia, July 2019