Introduction

NAHS funded a number of houses at Yarrabah in Queensland. Photograph David Campbell.

Five-bedroom house, Yarrabah, Qld.

Three-bedroom house, Canteen Creek, NT.

Four-bedroom house, Bawinanga, NT.

Three-bedroom house, Doomadgee, Qld.

Three-bedroom house, Umbakumba, NT.

Three-bedroom house, Daguragu, NT.

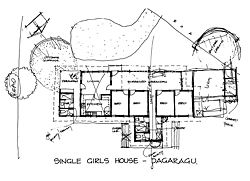

Model for a single women’s house at Daguragu, used during consultation. This is one of four house types built at Daguragu.

Working plan. Specific needs for a single women’s house at Daguragu included secure overflow sleeping areas, separate bathrooms for visitors and outside cooking areas.

Health is not merely a matter of providing doctors, hospitals, medicines or the absence of disease and incapacity.1 The now-defunct National Aboriginal Health Strategy (NAHS) was released in 1989 to set an agenda for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health. It recognized that Aboriginal peoples’ conception and perception of health is related to all aspects of life – the physical environment, dignity, community self esteem, and justice. Federally funded housing had a distinct place in the NAHS agenda. It was delivered with a consultation-intensive approach and at a scale that was small enough to allow local input to construction and maintenance, and large enough to have a significant impact on communities. But will its lessons be forgotten in the drive for new economies of scale?

Project delivery under the NAHS Environmental Housing Program involved evaluation, consultation, design, documentation, supervision and reporting. Deborah Fisher Architects and Build Up Design were engaged as project managers for the design, detail, documentation and contract administration of new houses, major renovations and infrastructure in the Northern Territory and Queensland between 2000 and 2005. The projects were mostly remote – Doomadgee and Yarrabah in Queensland, and Canteen Creek, Umbakumba (Groote Eylandt), Bawinanga Outstations and Dagaragu in the Northern Territory. The program was managed on behalf of ATSIC by Arup, who established the initial scope of projects, writing terms of reference for project managers’ services, monitoring and reporting on the progress of the projects.

Deborah Fisher and Simon Scally, principals of the two architectural practices, speak positively about the program, impressed that its systematic approach allowed consultants the time and fees to do their job thoroughly and thoughtfully – to engage with the community and provide appropriate and quality housing, community development and training opportunities. Both architects had extensive previous experience working for Aboriginal clients – Fisher as senior architect at Tangentyere Council between 1992 and 1998, and Scally from 1992 with ongoing work for Bawinanga Aboriginal Corporation (the service organization for Maningrida outstations in Arnhem Land). They agree that this experience gave them the confidence and skills to adapt design strategies and deal with political challenges.

Unlike its precursor, the Community Housing Infrastructure Program (CHIP), NAHS involved substantial amounts of money. Budgets of $2–3 million allowed up to twelve houses to be built per project, making a significant difference to communities. CHIP projects were limited to around four houses, while the current thinking aims to deliver fifty houses or more per project. These large numbers, and the speed required to deliver them, says Fisher, will most likely result in reduced client consultation and local employment. Small local and regional building teams, though well-armed with knowledge of the challenges of their locations, will be less able to provide the scale and speed of service required.

NAHS has been succeeded by the National Strategic framework for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health of 2003, which considers contemporary policy environments and planning structures in its approach to health. In the Northern Territory, the Strategic Indigenous Housing Infrastructure Program (SIHIP) is about to begin – a jointly funded program of the Northern Territory and Australian Governments. SIHIP aims to deliver $647 million of new and upgraded serviced land and related infrastructure, and new and upgraded housing in remote communities across the Northern Territory over the next five years. This is a large-scale regional approach, and Scally believes its aim is to attract big national builders and establish economies of scale to drive down prices.

Under NAHS, Fisher and Scally were able to devote significant attention to research and consultation at the beginning of each project, and thereafter produce a design report. Financially supported to do so, the architects spent time in communities and consulted with a number of parties – the community councils, community staff, the clinic, local health boards, local government organizations’ training boards, and importantly, the prospective householders. The NAHS approach allowed the architects to uncover the detail of things, and to provide a full service – in particular allowing for adequate assessment and consultation and, most importantly, adequate visits during the construction stage. In contrast, the CHIP consultation was secured on a tender basis, and being cost-driven, involved a minimum amount of time. Many housing failures resulted, say Fisher and Scally. The frequent site inspections possible under NAHS were critical for maintaining design intention and construction standards, particularly given the remoteness of many projects.

Many factors were assessed as part of the NAHS evaluation process – the existing housing stock (number, condition, and occupancy rates); housing need; lifestyle issues; site availability; site suitability; community capacity and options for construction or training; electrical, water and sewerage system capacity; climate; and general health issues. The latter were discussed with clinic staff and attempts were made to identify how the current housing stock was contributing to the health issues.

In general, the housing/health issues identified by Healthhabitat were seen in the communities Scally and Fisher worked in – overcrowding, dust and mud, inadequate or substandard wet areas for household numbers, inadequate or substandard food preparation areas, inability to control pests because of deteriorating building fabric or lack of control, inadequate ventilation, and inadequate maintenance. Scally laments that while occupants are often blamed for damaging their housing, inappropriate design and poor construction of the housing is often the cause of damage.

Fisher and Scally found they were paid at standard rates for NAHS work, as their fee was separate from the construction budget, and a quality-based consultant selection process (favouring experience) was used. Clients thus didn’t feel that they would receive “less house” if they selected a more expensive consultant. By comparison, Fisher and Scally’s previous work in this field (such as for CHIP-funded houses) had to be subsidized by other work. They found it difficult to generate income from projects that had a grant inclusive of fee. “There was a commitment by us to do that work,” says Scally. “Other practitioners, such as Paul Pholeros, are in the same boat. We have a lot of admiration for what he’s doing.”

Narelle Yabuka is assistant editor of Architecture Australia. She worked with Simon Scally and Deb Fisher to compile the overview and interview.

1. Australian Government, Preface to the National Aboriginal Health Strategy, 1989. http://www.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/Content/health-oatsih-pubs-healthstrategy.htm#1989 accessed 10 July 2008.

Lessons learnt — Deborah Fisher and Simon Scally in conversation

A curved windbreak was used at Canteen Creek for both privacy and shelter. Its position could be customized to suit house orientation and householder requirements.

The use of durable fixtures was particularly important on remote sites such as Canteen Creek. Customized colours offered personalization. Photographs Pam Lofts

19 Deborah Fisher and Simon Scally conducting design consultation at Daguragu with Connie Ngarmeiye

Deborah Fisher and Simon Scally conducting design consultation at Daguragu with Lindsay Ricky and Priscilla King.

Deborah Fisher and Simon Scally conducting design consultation at Daguragu with Queeny Bernard. Photographs Deborah Fisher and Simon Scally

Simon Scally The cost of housing in remote areas is so high, that it’s important to get it right. However, consultation with individual householders is sometimes controversial. It can be argued that other public housing recipients don’t receive this level of involvement, that it raises the cost of housing, that it results in a loss of standardization and therefore adds to cost and sets up inequities. We have found that the consultation process adds significantly to the project outcomes. It engages the householders and community by offering genuine participation. Householders are aware of the budget constraints and make decisions within them.

Deborah Fisher People have individual needs. It’s dangerous to make generalizations about the key issues faced by different communities and the consultation techniques that should be used. For example, people at Yarrabah are very different to people at Dagaragu. You need to understand your clients before you go and talk to them.

SS Yes, you need to read their history, and find out their cultural makeup before you go there. In one area where we’ve worked, there are thirteen different languages within a 200 kilometre radius. You can’t make generalizations about groups, because people are diverse. However there may be commonly occurring lifestyle issues that jar with typical Western housing models. Often, just one of the bedrooms of an Aboriginal house will be occupied by a family unit, or by three teenage boys, or by three teenage girls. If that many people live in a house, there will obviously be an impact on wet areas. High usage of wet areas leads to leaks and breakages. The architect can position wet areas in locations where, if breakages occur, there won’t be leakage into the rest of the house. Also, their placement on eastern or western walls will harness heat for drying, and provide a degree of insulation to the adjacent rooms. It’s not difficult to suit peoples’ needs if you understand their lifestyles.

DF You can’t just talk to a short-term council administrator. You need to build relationships with people – particularly with Aboriginal leaders and the future housing occupants. There’s often a political structure within communities. You need to know who to work with to get a good result. Housing needs are often stereotyped by non-Aboriginal managers in remote communities. Ideas are sometimes good but poorly thought-out and conceived. When these people leave, their legacy remains, and this can damage future processes. It’s important for practitioners to be experienced – to be able to recognize potential problems and work around them. Also, it’s good to have both genders working on the design team. This allows people to feel more comfortable when discussing issues that apply more to men or women.

SS The NAHS consultation phase included about six site visits. A visit would last three-to-five days. After a two-week break, you would revisit those people, and in the time between trips people had time to think and formulate responses. This process can be very beneficial from a cultural point of view. For example, a wife may not feel comfortable publicly contradicting a vocal husband about kitchen design considerations. NAHS allowed time for the clients to reflect.

DF The time between return consultations was very important. It enabled people who, for various reasons, may not want to speak publicly, to talk amongst themselves in between consultations. We would also do work overnight while we were in the community, and come back to the clients with drawings the next day. This reinforced the architects’ commitment to people. It assured them that we were doing our best to meet their individual needs. Clients would trust that we were listening to them.

SS Daguragu community meetings were held to discuss the issues related to the existing housing, the town, the new housing, and where it should go so that families were appropriately located in relation to their cultural and social obligations. These meetings were spirited and the attendees were very engaged. In one particular session, the community had a two-hour discussion in language. It was a positive meeting with a good result. The community was involved and happy, and the architects’ role was limited to recording the agreements.

DF The houses eventually built respond to the needs of the community. They are climatically responsive, culturally sensitive, and highly durable with good fittings and fixtures. In the long term, they are easier to maintain and repair.

SS The consultation process does not necessarily result in a multitude of different designs. We found, in particular at Dagaragu and Canteen Creek, that even though we had detailed individual family consultations, we were still able to standardize the house designs. There’s still the capacity, within those designs, to consult with the end user on how it may or may not suit that particular family. The family could make decisions – for example on the position of wind breaks, verandahs, outdoor kitchens, driveways.

DF There are clearly economic benefits to this kind of approach, and it’s much easier for builders to price, too.

SS At Daguragu, for example, there were twelve houses built to four designs. One of these was different because it was a women’s building with specific needs. Eleven houses incorporated the same truss design and replicated bathroom and kitchen layouts, which simplified construction for the locally-based steel fabrication team. Houses were customized to individual families with colour schemes, orientation, and the location of a windbreak element protecting an outside cooking area. The consultation process enabled informed choice by both the householders and the Daguragu Community Government Council.

DF An approach often taken with Aboriginal housing is to put a verandah all the way around the house, but large areas of it don’t get used. It’s expensive and creates a massive footprint.

SS Well-positioned verandahs are better used. They can be placed with consideration of the sun, wind, privacy and views. We’ve found that some clients like to be able to survey the shops, which are often considered the centre of town. Some clients like to see who’s coming, who’s going, who’s up to what.

DF People are often stereotyped as being transient, but in our experience that was not often the case. In instances where this may have occurred, we believe an inclusive design process with a group of householders is better than no client input at all. If people do move, the house will probably fit another community family who are likely to have similar social, cultural, environmental and climatic needs. When you consider the overall cost of a building, including maintenance (particularly when it is remote), the consultation process is not expensive. Getting it right is a really good investment. And furthermore, allowing people to be involved in the decision-making process is empowering.

SS And it’s really no different to the process used for speculative houses in town.

Simon Scally is the principal of Build Up Design in Darwin.

Deborah Fisher is a principal of Fisher and Buttrose Architects, Cairns. They spoke with Narelle Yabuka in July 2008.

Variations on a house type at Doomadgee. Three house types were built here, with variations including open or enclosed kitchen/living relationships, verandah arrangements, egress, and bedroom adjacency relationships. Photographs Kerry Trapnell.

“homes” at Yarrabah

Yarrabah, just south of Cairns, has a population of around 3,000 people.

Four years after Fisher and Scally’s work at Yarrabah, homes have been personalized further. Photographs David Campbell.

Deborah Fisher with Cheryl Graham outside her Yarrabah home.

Visiting Yarrabah again and catching up with some of my old clients from four years ago was a good thing. I was received warmly and people were happy to have photographs of their homes included in Architecture Australia. It is often confronting visiting houses and clients down the track; this time my fears were allayed and the houses seem to be very well used. The built-in seats on the front verandahs showed signs of lots of use. The kitchens, with their stainless steel bench tops, appeared functional, and the durable fittings of the interiors still looked fresh.

So, had our in-depth analysis, research, participatory design and consultative processes achieved the goals of the NAHS Environmental Housing Program? Had it made an improvement to the occupants’ health? It is unlikely that I, as an architect, could answer that question. All I can provide is an assessment of the functionality of the houses. At the end of the twelve-month defects period, all houses were still in good condition and had been personalized. In some cases, beautiful gardens had been created.

On reflection, however, I think that the most important aspect of our work on this project was facilitating the creation of homes. With regard to health and housing, it’s important to consider mental health as well as the physical aspects of health. Depression deserves attention. The creation of ‘homes’ is an imperative. A comfortable, well-functioning home will support – rather than place stress on – human relationships. In terms of maintenance, a house that lasts longer is less stressful on a family. If a home is well designed, its overall cost will be lower.

When people are part of the design process, they’re more likely to feel that the resulting house (or home) is theirs. The Yarrabah homes seem loved. Perhaps if there is another NAHS program after the current round of mass-produced top-down housing delivery has become unfashionable, it will be called the ‘National Aboriginal Home Strategy’ instead.

Deborah Fisher

Photographs

Pam Lofts 10-18

Deborah Fisher and Simon Scally 19-21

Kerry Trapnell 22-27

David Campbell 28-31