In 2015, London architect Nick Wood was wandering the streets of Sydney, pushing a bright orange trolley with a mirror on the top, asking passers-by what they thought of the view.

As part of the Droga Architect in Residence program, Wood spent three months in Australia studying the humble street awning, exploring its role in the public realm and investigating ways that architects might be able to intervene in this space. Working with architects and art students from UNSW Sydney, he developed a series of models and prototypes before erecting a novel awning on the campus.

Five years later, as part of a series looking back on the Droga Architect in Residence program, ArchitectureAU’s Josh Harris called Wood in locked-down London to speak about awnings, the intersection of architecture and making, and the value of residency programs. Wood is the founder and director of How About Studio.

Josh Harris: What was it about street awnings in Australia that interested you?

Nick Wood: I did the residency in 2015, but my wife is Australian and I first visited Australia to “meet the parents” in 2013. The street awnings are very different to what we’re used to in our UK high streets, [where] you’re used to walking along and having this big blue sky above and having this openness to the world. I immediately noticed it on my first trip to Australia, this “lid” on the experience in the street. And then you think, “What is this thing?” There are some beautiful, ornate, traditional awnings out there, but the general stock has fallen away.

This became the focus of my proposal to the Droga architecture residency. There is so much potential in these spaces, created by these structures. There’s a lot of discussion about the footpath and activating footpaths, and lots of amazing schemes going on globally about how we can bring life back to the street. And it felt as if, in climates like Australia’s, where the awning, environmentally, plays a huge role, they could bring a lot more to the experience of the community and the town. That was the basis of my proposal. And accompanying that was my own studio practice, which is very much about the balance of being an architect and a maker. And this was a scale of architecture that I could talk about, but also engage with through making.

The awning prototype created with UNSW and UTS students during the residency.

Image: How About Studio

JH: It’s interesting, because awnings are so ubiquitous in Australian cities, but they’re perhaps not talked about that much. They’re just kind of there.

NW: Yes. That was something that I realized early on. I was walking around and spending a lot of time looking up and enjoying this personal survey of the awning when I first started the residency and realized that I really wanted to understand the general public’s perception of what this thing was. So I built this mirrored trolley, which was bright orange, because I saw a lot of bright orange around construction sites in Sydney, but also there are these mirrored trolleys you get in English cathedrals which you can wheel around and use to look at these amazing vaulted ceilings.

I basically walked that [trolley] around miles and miles, and it was a conversation point. If you walked up to someone with a clipboard and said, “Can I talk to you about the awnings?”, it would be very different to standing around this mirrored table and just having a chat. And I think what you just said there typifies a huge number of responses: “Well, it’s there to protect us from the sun, right?” It’s really exciting to see that there’s this unexplored or unimagined side to it.

JH: Did you get any surprising responses? Anyone with stories or strong opinions about the awnings?

NW: When I was walking through Glebe, I think, I was talking to a shop owner there – actually, she wasn’t the owner, she was the tenant, but the awning was owned by her landlord. So, although she had a sign on it, it’s a privately owned structure which exists in public space. She felt that she didn’t have enough control over it, but that it represented her as a retailer. And from the public perspective, there’s a lot of money spent maintaining the path and putting in greenery and benches, but the awning – which is so much a part of that experience on the street – is privately owned, so we rely on the developer or the private landlord to invest in his or her own awning. So that opened up different ways of looking at the awning, because the experience is one thing, but there’s a whole background of evolution and legislation that got us to the current situation.

A work in process.

Image: How About Studio

JH: Right, it’s literally the private extending into the public realm. What about the evolution of the awning form? How has it changed through the years and how do awnings perform in buildings that are being made today?

NW: When the first settlers arrived, there was an importing of European styles for the first buildings and settlements. So, you suddenly realize these buildings need something added to them. And I think it came in from India, the original verandahs. And at the start, it was something that only wealthy people would have – I guess mirroring the birth of air-conditioning, in a weird way. But once it moved onto the street, you got these early paintings and drawings of these really interesting filigree timber structures, and in some cases they became multistorey structures that concealed the building behind them.

Then, in Sydney, there’s this moment where there’s all these accidents happening, as people can’t drive cars properly yet. There are these huge pictures in old newspapers of the posts being wiped out of the awnings and suddenly it became law for them to be cantilevered. I’ve identified that as being a really key moment in history where awnings became this out-of-reach, out-of-touch thing, whereas previously, these timber posts gave it tactility, which people could engage with more, and it was more of an enclosed space. Once it became a cantilevered thing by law, in (I think) 1908, it changed the trajectory slightly. Add to that the big reorganization of cities like Sydney around creating bigger highways and you lose these beautiful older awnings, and the law says you can’t rebuild them. I guess this is how we got to where we are today. I know Melbourne still has those long stretches with hoisted awnings. But in Sydney, from my experience, they only really exist in preserved places like The Rocks.

Image: How About Studio

JH: You talked about how you like to focus on making things. How did that influence your approach during the Droga residency? I know you spent a lot of time with students making prototypes for different types of awnings.

NW: The first draft of my proposal was to set up a workshop in the corner of the Durbach Block Jaggers apartment. We didn’t get quite as far as that, but I had a good space set up for model making. But then in the third or fourth week, I was introduced to someone at UNSW and their workshop team, and I suddenly had facilities similar to what I had in London, and then also at UTS, so I had the ability to start making things at a larger scale with a broader range of materials. Most of the residency was research-based and then, over the last month, I started to develop this idea of a design which was meant to be a prototype that explored some of the themes from the residency.

I developed that with plaster models and smaller tests using reclaimed timber. And then we had a big blitz with maybe 30 students from UNSW and UTS – a mixture of design and artist students helping to put together this prototype. And we finished with an event where we could show all the models, all the research, and this full-scale prototype at the end of the residency. It was built on a shoestring. But, funnily enough, that became part of my interest in the awnings – the idea that a private developer builds something with low maintenance in mind, and they want it to last forever. But awnings aren’t buildings; they should be seen more as a temporary structure or temporary architecture, which opens up a whole new catalogue of materials that lasts a year or two, or five years. We could allow these things to degrade, change in time, which means that they have to be replaced and it allows the high street to become a slightly more difficult, changing thing, rather than just a fixed, tin-clad box.

JH: Originally, you wanted to install the prototype in the wild, above a footpath. What happened there?

NW: I was told about this fairly engaged developer, Theo Onisforou, who was trying to turn Oxford Street back into being a destination. I reached out to him and he had a shop on this corner which didn’t have an awning, and he was happy for us to build the prototype there. We were going through the motions but, unfortunately, with the time and budget constraints, we couldn’t quite get past the legislative and engineering requirements. We had a pro bono engineer, but we couldn’t quite get the council on board in time.

So we skipped back across the road to UNSW, where there’s this really interesting terrace which replicated the proportions of the street anyway. I think that by starting that process [on Oxford Street], it allowed us to engage a little bit in what the complexities are of doing something that is essentially quite simple, [except that] the public space, the public footpath, comes with a large amount of red tape.

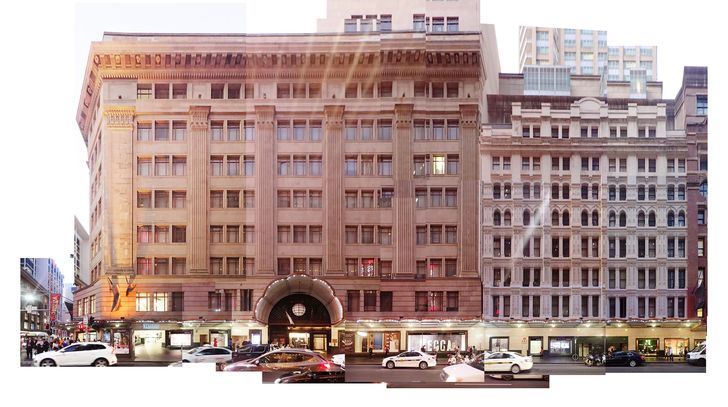

One of many Sydney streets where awnings protect pedestrians from the sun.

Image: How About Studio

JH: That’s interesting in itself, the process of discovering the difficulties involved.

NW: Yeah, I think that’s the exciting potential – if you can find a way of working, or create a system of being able to work in this awning space, you can open up so many opportunities. The scale of it opens it up to young architects, young designers, to try out ideas. It just needs a framework or a network … I think it’s screaming out for someone to facilitate a testbed – perhaps a particular street that can be given over for a five-year period of continual change.

JH: Have you been developing these ideas? What sort of impact has the residency had on your practice since?

NW: Yes, especially with lockdown, I’ve started to really get back into pulling things together to share. From a studio perspective, the [residency] experience of going into this new place to explore and research and have a dedicated period of stepping back and thinking about my practice was really useful. And the sharing which happens between professionals. But also just getting on the street and feeling that that was a very responsive process.

The awning is a temporary structure and since the residency, my own work has really started to get deeper into the power of temporary interventions and structures within the city, to test ideas and build consensus amongst the community. The awning has this vast and amazing history and a lot of my projects do tap into these unseen, rich narratives. [The residency] reinforced for me that when we study architecture, we’re talking about buildings and often forgetting the full scale of architecture – the awning being at the small, simple end of that scale. Large, complex, permanent structures – say buildings – are one part of architecture practice. And I’m really learning to embrace the practice that I’m doing, which is very much about making.

JH: What value do you see in architect in residence programs in general – would you recommend that people take part if they get the opportunity?

NW: Yeah, definitely. When you’re at university, you’re unfettered by the commercial aspects of architecture. It’s nice to step back from those cycles and really think about what is that you are focused on producing and how you want to produce things. But there’s very limited opportunity within practice to really get back to engaging with what you’re interested in. I think it took a bit of stepping back and thinking, “How do I approach making and architecture together?”, to embrace the fact that I don’t necessarily have to scale what I’m doing towards a conventional architecture practice. I think that would be something everyone can benefit from it, especially those who are trying to grapple with what their practice is, and if they have interests that don’t quite fit into the traditional model.

JH: I guess the lockdowns many of us are experiencing also offer a chance to step back and assess things a little.

NW: Yes. With the awning concept, I had been reluctant to work on it remotely because I felt it’s strange to work on a project for a certain place from somewhere else. But now it almost feels that with lockdown, that is just the way we’re all working at various scales, whether it’s being away from your office or at your home. It’s given me a push to start to pull together five years of sketches, photographs and thoughts. Hopefully, by the end of lockdown, I’ll emerge from my home and have some more things to share about the awnings. There were things that I felt I was scratching the surface of during the residency, which I’ve now had some time to think into a lot more.

JH: How did you like living in the Durbach Block Jaggers apartment during the residency?

NW: It’s an amazing place to be dropped into. I’m a huge fan of Durbach Block Jaggers, so to tap into some of that history was really inspiring. But it’s also just such a calm place to be; you’d think that being in the middle of the city, you’d be in the hustle and bustle, but it was actually such a quiet studio space. Once I set up the messy, loud workshops at UNSW and UTS, the apartment became a really great space for thoughts and a nice place for meeting people occasionally.