Late in 2019, before it all changed, I drove out to Broadmeadows on a balmy and clear-skied evening to hear Kerstin Thompson talk at the opening of the first exhibition to be held at the renewed Broadmeadows town hall. After insightful words, drinks and a walk around the carefully considered and restored interiors, guests wandered outside and around the “handsome beast,” as the architect had called the building. To some delight, radiant colour from the new glass walls of the extension shone through the dusk sky. There was optimism in the air.

Seven months later, during Melbourne’s long, grim winter of lockdown, we watched the Victorian Architecture Awards online from home, with the Town Hall Broadmeadows taking the top gong – the Victorian Architecture Medal – after first winning in the Heritage category and gaining a commendation for Public Architecture. The absence of freedoms – those of movement, gathering, participation, celebration – were reinforced by both the lockdown and the public nature of this project. These are the communal spaces we value and in which we yearn to gather again.

The restored entry to Town Hall Broadmeadows.

Image: John Gollings

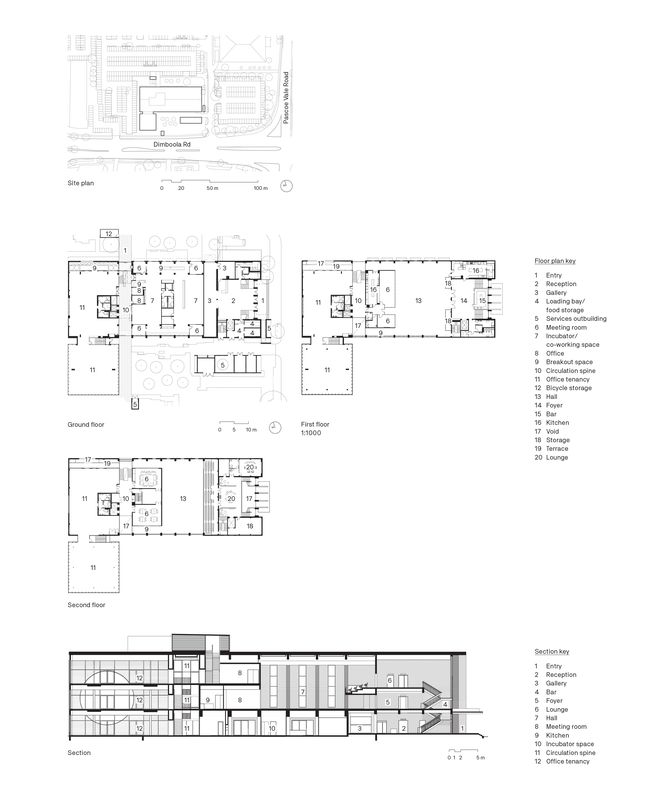

Civic buildings, especially those of assembly, are essential for livelihoods. And what is impressive about Town Hall Broadmeadows is how it works in the road-based Australian suburb to make good on its promise of openness and generosity. If nothing else, it was a big hall for the community to use – for weddings, bands, parties. All of which, after years of neglect, will now be able to happen again. Kerstin Thompson Architects (KTA) has retained and transformed this important local landmark, known in its heyday as the “pink elephant.” The project represents a gradient of transformation, moving from subtle restoration of the primary east facade to full reconstruction and addition at the western end.

The original building is rich in authenticity, presence and cultural memory. The decision to retain the structure was not a given – a masterplan from the early 2000s had it being demolished. But the community ultimately saw its value, and the city council succeeded in appointing an architect with a particularly strong understanding of how to treat existing buildings. KTA pushed for the building’s red brick to remain (and not to be rendered), but also saw how new openings to the north side could be of benefit, and how to handle a sizeable extension on the south side, facing Dimboola Road.

The existing main facade of the building, which remains essentially unchanged, sits back from busy Pascoe Vale Road, with an on-grade carpark acting as a forecourt and giving the building prominence on this busy corner of northern metropolitan Melbourne. In addition to this setback, the building follows some other key rules of civic buildings: the facade is essentially classical in its conception and uses floating shallow arches to form a distinctive entry canopy.

The existing main facade of the building, remains essentially unchanged,with an on-grade carpark acting as a forecourt to the building.

Image: Dan Preston

Two new building elements have been added within the setback from Dimboola Road, to the south of the building: an illuminating glass box protrudes into this freshly landscaped area (previously a carpark) and a low pavilion containing servicing is designed to have greenery creep over it in time. The most dramatic change, however, is within the footprint of the existing long building. The north facade has been radically transformed, with major cuts into the original and reconstructed fabric. Previously, depot and office buildings were housed up against this facade, but these were removed some years ago, leaving the now sheer wall at liberty to be opened up.

The big move here is a grand civic circular opening – recalling Louis Kahn at Exeter and Dhaka but also precedents closer to home, such as the National Gallery of Victoria. It’s a deep cut, with a glass wall behind, creating a space for a balcony with garden to service the new office areas. The arch and surrounding wall are rebuilt brickwork, in a mix of bricks similar but subtly different. This all sits under the existing roof line, with original parapet details reconstructed at the western end. The whole back end of the building has been effectively rebuilt and KTA has made the most of this opportunity.

KTA avoided rendering the red brick of the original building, which was affectionately known as the “pink elephant.”

Image: Dan Preston

The second move, which links the north and south sides of the building, is a three-storey arcade the width of a structural bay and glazed on both ends. The arcade creates an important north–south public link, reorientating the wider site to a pedestrian experience. A paved brick floor and exposed concrete floor slabs give this space a laneway-like sensibility. Stairs and bridges connect the two sides of the building. The ceiling in this linear space is both wonderful and referential – a series of shallow white arches is a direct reference to those of the entry canopy, and bestows the same benefits of modulating light and creating a sense of enclosure.

The arcade gives access to the three new floors of office space that occupy the back of the building. These are on one hand generic, with acoustic ceilings and curtain walls – but the shell is beautifully detailed. A steel cantilevered edge detail supports the glazing, with continuous engineered timber mullions running the height of the glass box. Views from the inside are abundant, with light on three sides. Views back to the giant circle opening connect the interior to the wider civic precinct to the north.

A three-storey arcade, with a laneway-like sensibility, has been inserted to link the north and south sides of the building.

Image: Dan Preston

The restored part of the building has two significant spaces: the refurbished entry foyer and the reconfigured main hall. In the foyer, new terrazzo flooring has replaced carpet, foregrounding the exposed red and cream brick and creating the sense of a palazzo. The foyer leads to the surprisingly shallow exhibition space, which takes up one bay of the old lower hall, while behind a solid wall is a new business incubator space; it seems that these spaces could connect to each other in some way.

Diligently restored floating stairs connect to the first-floor foyer, where a bar has been carefully inserted in front of the tall glass of the facade, its joinery kept low to maintain the outlook eastward. Hanging in the void above is a commissioned artwork, Crossing the floor by Robbie Rowlands. A timber spiral made from the original floorboards of the lower hall, the work helps to link the foyers together.

Crossing the floor by artist Robbie Rowlands, is made from the original floorboards of the lower hall and helps to link the foyers.

Image: Dan Preston

The main hall is about half its previous size, making it seem more wide than it is deep. Its fundamental feature – tall, modernist glazing on both sides, north and south – remains. An existing viewing gallery continues to hang in the space, its fluted balustrade underscoring the classical aspirations of the original building. A new black-stained plywood box houses toilets and support spaces, bringing the back wall of the hall forward. Meeting rooms at the bottom of this ply box open into the main hall and can be used in conjunction with it. The black box sits clearly away from the north and south walls, allowing them to continue past and making it clear that the new insertion is just that.

The 2020 Victorian Architecture Awards were widely discussed as foregrounding adaptive re-use, but do projects like Town Hall Broadmeadows really fall into this category? In many ways, the town hall’s use has stayed the same (functions and events, with supporting office space), but the building has just got better. Rather, this project runs the gamut of conservation strategies: restoration, reconstruction, demolition and extension. It is a showcase in how to deal with an existing building that does not have heritage protection. This elective heritage acknowledges cultural and architectural significance but allows for substantial changes.

According to the City of Broadmeadows, when the town hall was first being proposed in the early 1960s, it was to herald “a new chapter in [its] history.” Sixty years later, the building is a link between this history and the multiple possible futures we now face. Back in the 1960s, “Broady” made things (mainly cars). It was a time of post-war optimism. Will our post-pandemic era be just as optimistic? KTA, through a comprehensive and skilful demonstration of how to rework existing buildings, has shown us how this optimistic past can make sense of the society we walk toward.

Credits

- Project

- Broadmeadows Town Hall

- Architect

- Kerstin Thompson Architects

Melbourne, Vic, Australia

- Project Team

- Kerstin Thompson, Kelley Mackay, Martin Allen, Lloyd McCathie, Tina Leal, Caroline Chong, Ben Pakulsky, William Samuels, Blair Henry, Hilary Sleigh, Tamsin O’Reilly

- Consultants

-

Acoustics

Marshall Day Acoustics

Artist Robbie Rowlands

Audiovisual Alder Technology Consulting

Builder Building Engineering

Building surveyor and accessibility consultant du Chateau Chun

ESD consultant Umow Lai

Electrical, fire, mechanical and hydraulic engineer Umow Lai

Facilities planning (kitchen) Maytrix Group

Facilities planning (workspaces) Coactiv8

Fire engineer Dobbs Doherty

Geotechnical engineer A.S. James Pty Ltd

Land surveyor Bosco Jonson (now Veris)

Landscape architect Simon Ellis Landscape Architects

Lighting consultant Bluebottle

Project manager City of Hume

Quantity surveyor Prowse Quantity Surveyors

Statutory Planning Urbis

Structural and civil engineer Perrett Simpson

Traffic consultant Traffix

Vertical transport consultant Umow Lai

Waste management consultant Leigh Design

- Aboriginal Nation

- Built on the land of the Gunung-Willam-Balluk people of the Wurundjeri

- Site Details

-

Location

Melbourne,

Vic,

Australia

Site type Urban

- Project Details

-

Status

Built

Type Public / civic

Source

Project

Published online: 13 May 2021

Words:

Stuart Harrison

Images:

Dan Preston,

John Gollings,

Kerstin Thompson Architects

Issue

Architecture Australia, March 2021