Laura Harding reviews six speculative visions for Sydney’s urban future, presented at CV08.

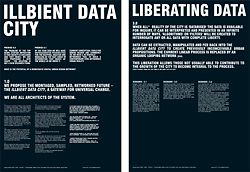

Panels from Room 11’s Illbient City proposal for the Sydney City Future Visions.

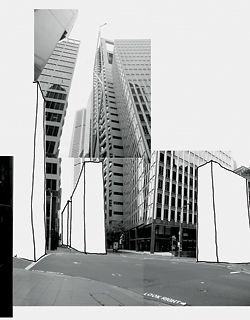

Tribe Studio’s 24-Hour City inserted low-rise housing into the CBD, on the assumption that cars had been banned.

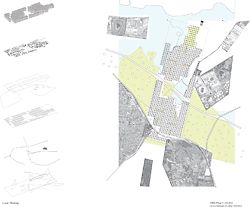

Scale Architecture’s Alt_City proposed an alternate CBD and replaced sprawl with density.

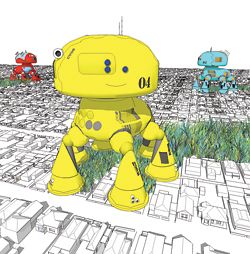

CV08, Andrew Maynard’s suburb-eating robot dog, which leaves virgin bushland in its wake.

Choi Ropiha’s new linear city, parallel to Sydney’s northern beaches.

Vector Guerrillas’ Global Planning Intelligence. “All urban decisions will be tracked, analyzed and allocated via a pervasive systems intelligence.”

As part of the 2008 Australian Institute of Architects National Conference, six emerging practices were invited to present a speculative vision of Sydney’s urban future. The proponents were asked to consider the local consequences of global effects – to explore the ways that climate change, social inequity, urbanization, displacement and growth will shape the urban environment by 2050. Three were asked to consider the city, and the remainder were given the task of confronting the suburbs. The proposals were exhibited publicly at Customs House and subsequently reviewed in jury sessions at the conference.

André Gide observed that “the true hypocrite is one who ceases to perceive his deception, the one who lies with sincerity”, and what ultimately characterizes the Sydney Future Visions is a disjunction between what the proponents believe they are offering and what is actually delivered. We are presented with “Illbient data cities”, “Post-cartographic complexity nets”, “organic loop networks”, “overlapping programmatic bands” and “meta-tools for shaping the city” as new ways of engaging with the complexities of the urban realm. Yet beneath the slippery verbiage and sleek imagery, the proposals really say that the existing complexity of our cities and suburbs at best bore and at worst overwhelm these “emergent” architects – who prefer to simplify them, destroy them, start anew, assume that technology will fix them or “solve” them with singular architectural gestures.

Room 11 details its proposal for the Illbient data city – a “4D digitally networked tool”, with which “all reality of the city is ‘datarised’ (sic)”. Planning decisions are to be made collectively on a forum/wiki/blog by “the professional or interested individual” and ‘‘algorithms or ‘filters’ will be created to interrogate any or all data with complete liberty”. The promise is freedom, but it whispers control. Data is not a panacea, the architectural skill is in knowing how to act in response to it, and there is no surer way to frustrate and limit freedom of action than ceding decision-making to a chorus of opinion, roused by self-interest.

Scale Architecture proposes Alt_City, an alternate CBD. This proposal is predicated on an intelligent critique of the Sydney Metropolitan Plan and an intention to replace sprawl with density. It proposes a strongly defined limit to the urban area and the intensification of activity within. Here, the theory is fine but the practice is fraught. The limit is a thoughtlessly drawn circle that inexplicably excludes parts of Sydney that already have substantially developed infrastructure and inherent density. Within the new city, we are promised a “radical alternative to the current model” but are actually offered prosaic “zoning” in regulating lines that divide the city like a pie chart, segregating functions between picturesque agricultural landscapes. Far from “radical”, this idea is eighty years old – it is CIAM to the core.

Tribe Studio’s project was well received by the conference jury, who applauded its interest in the “24-hour city” by the insertion of low-rise housing into the existing city centre. The proposal assumes that by 2050 all cars have been banned – a fortuitous premise indeed. The now redundant street reservations are lined with eighteen linear kilometres of thin cross-section buildings, with uniform height and a standardized offset from the existing street walls. Intersections are re-formed as small public squares. This scheme is quintessentially Sydney – inviting the forces of speculation to invade the city’s public domain by the transfer of almost a third of it to private ownership – a CBD land release of sorts. It promises diversity, but delivers homogeneity. Each street is treated with the same methodical hand – ignoring the potential for existing building stock, uses, orientations, topographic conditions, adjacencies, material character, microclimate, outlooks and alignments to inform the placement and modulation of the insertions.

The suburban proposals had the much tougher task of attempting to resuscitate a flawed model. One team opted for homicide, one chose euthanasia and the other initiated life support.

Andrew Maynard presented CV08, a suburb-eating robot dog that would consume the suburbs and leave virgin bushland in its wake. He assured us it was satire, but it sounded like lazy cynicism.

Choi Ropiha sold lifestyle while ignoring the sprawl of the existing suburbs by forming a new linear city parallel to the northern beaches. This appeared to provide the dual benefits of “dense cosmopolitan lifestyle” and ready access to surfing. There was an attempt to layer this with something more fundamental. Ideas of supporting transport networks, automated underground material distribution systems and energy harvesters were included, but were really window dressing, as their efficiency in such an elongated, linear system is highly questionable.

Vector Guerrillas made a late play for satire with its theory of Global Planning Intelligence, but looked very serious indeed. There wasn’t a trace of architecture or urbanism in this “proposition” – just the tired premise that technology will save us. There was a comical discussion about the “physicality” of data, followed by the screening of a very polished short-subject film that was aptly short on subject. We were told that “islands of integrated energy technologies will sustain suburban regions” and shown sci-fi energy creation towers that appeared to leave the suburbs intact in their existing form. We were offered no explanation as to why the existing form is worthy of retention.

A member of the city jury, Michael Hensel, went to the heart of the matter when he asked the proponents, “Why all this large-scale intervention? Why not a thousand small projects?” The answer is that to approach the city in this way requires an interest in the messy, visceral realm of reality. It requires an ability to approach the quirky, imperfect nature of human cities with curiosity and optimism, rather than a desire to neaten and tame. It requires an interest in the particular and the specific rather than in homogeneity and the broad brush. It is about maximizing the opportunities and freedoms for architecture rather than enslaving it to image. To borrow Raphael Moneo’s beautiful analogy, it is about opening up and preparing the chessboard – not about playing the game alone.

Laura Harding works with Sydney-based practice Hill Thalis Architecture + Urban Projects.