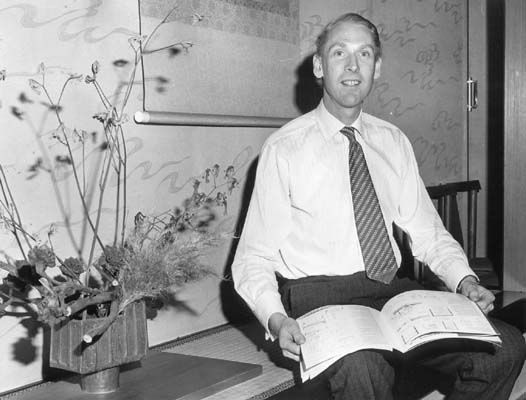

Professor Allan Rodger.

Image: University of Melbourne Archives

Allan Rodger, professor and chair of architecture at the University of Melbourne from 1974 to 1996, passed on 14 June 2022, aged 87. He leaves three children and eight grandchildren. Rodger was a pioneer of environmental and social thinking in architecture and architectural education, both locally and globally. Born in Scotland in 1935, he grew up infused with the practice of making things – his grandfather was a cabinet maker and joiner, his mother was a seamstress and his father was an architect (educated through apprenticeship, as most architects were in those days). He first studied engineering science at the University of Dundee and then proceeded to architecture at the University of Durham. His approach to architecture was modernist in the earliest sense of using modern materials, forms and technologies to address broader social issues.

On graduation, Rodger worked in London before taking over his father’s practice in St Andrews, on the east coast of Scotland, where he designed a range of housing and community buildings. He commenced a teaching career at the universities of St Andrews and Edinburgh, where he became critical of the ways in which modernism in architecture was reduced to a corporate style and in which creative thinking was reduced to formalism. He also taught for several years from 1968 at Khartoum in Sudan – a key period of exposure to a very different kind of architecture, and the ways it adapts to culture, climate and economy. In 1971, he was appointed a senior lecturer at the University of Edinburgh and, in 1974, to a chair of architecture at the University of Melbourne.

Rodger arrived at the University of Melbourne at a time when there were only two professors of architecture (there are now 10). He held the chair of architecture until his retirement in 1996; during this period, he also held appointments as head of department and dean of faculty. Upon retirement, he remained active in a broad range of community and consulting engagements.

Rodger was a passionate proponent of new ways of thinking about architecture, cities and landscapes. He was a relational thinker who was not so much interested in things in themselves as in the interconnectedness of things. This was not easily understood by those committed to a formalist architecture or fixed masterplans. Rodger tended to find his allies outside the tent – in landscape architecture, human ecology and many other disciplines. He was always passionately connecting theory with practice, drawing connections between projects on the ground and the big issues of climate change and global poverty. Forty years ago, he was focused on the implications for the built environment professions of what was then called the “greenhouse effect.” Placing these issues at the top of the profession’s agenda at every scale, from local to global, was his life’s work.

At the international level, Rodger was the inaugural convenor of the working group established by the International Union of Architects (UIA) to address the challenges of the “greenhouse effect.” In a key paper to the first “Earth Summit” in Rio de Janeiro in 1992, he suggested that the built environment was at once the “victim,” the “villain” and potentially the “white knight” of climate change. The role of the victim is now apparent in increased fires, floods and hurricanes across the planet; the villain in the high levels of carbon emissions we produce to create buildings and cities; and the white knight in well-designed, green cities that reduce emissions.

At the grassroots level, Rodger was instrumental in the emergence and governance of a range of local initiatives: the CERES Community Environment Park in Brunswick and the Maryborough project for self-build housing, to name just two. He played a key role in many philanthropic, government and community organizations, including the Banksia Foundation, Greenfleet and Greenhouse Action. In 2015, he was awarded the Leadership in Sustainability Prize by the Australian Institute of Architects, of which he was a life fellow.

Rodger also brought new forms of thinking to architectural education. As head of architecture at the University of Melbourne in the early 1980s, he split the five-year degree into two, with the first intended as a generic degree prior to professional specialization. This initiative was dismantled in the late 1980s, but it is the model we have returned to more than 20 years later. Rodger loved intellectual debate and he understood that the main game in any good university is always the production of ideas. For him, this meant connecting architecture to a larger world by marrying the rationalities of good science with the creativity of design. In one of our last conversations, he said: “Systems thinking is pretty damned good if you know where you’re trying to go. But leaps of imagination are also very important.” In all these ways, Rodger’s impact will linger and he will be greatly missed.