Born and educated in Melbourne – a city about which he had an encyclopaedic knowledge – Hugh O’Neill left a legacy that extended far beyond his native land. Several generations of students in Southeast Asia, China, India and Sri Lanka were inspired by his mentoring.

O’Neill’s expertise in his chosen field of architecture was the technical basis for his appointment as a lecturer in the Faculty of Architecture, Building and Planning at the University of Melbourne in 1961. (He had studied there himself from 1951 to 1956.) But that was only part of his achievement, for he was an extraordinary teacher. It is impossible to quantify the importance of dedicated teachers, but the ability to inspire in students a desire to go beyond the technical requirements of a chosen field is rare. O’Neill embodied that quality, which was integral to his understanding of people and society. He could always see the connection between architecture and those who lived with it. He understood context and had an appreciation for the essential role of urban planning, for the need to consider a building as part of the whole and not just a single showpiece. He taught at the faculty until after 2000, when he was also appointed as an adjunct professor at Deakin University’s Cultural Heritage Centre for Asia and the Pacific.

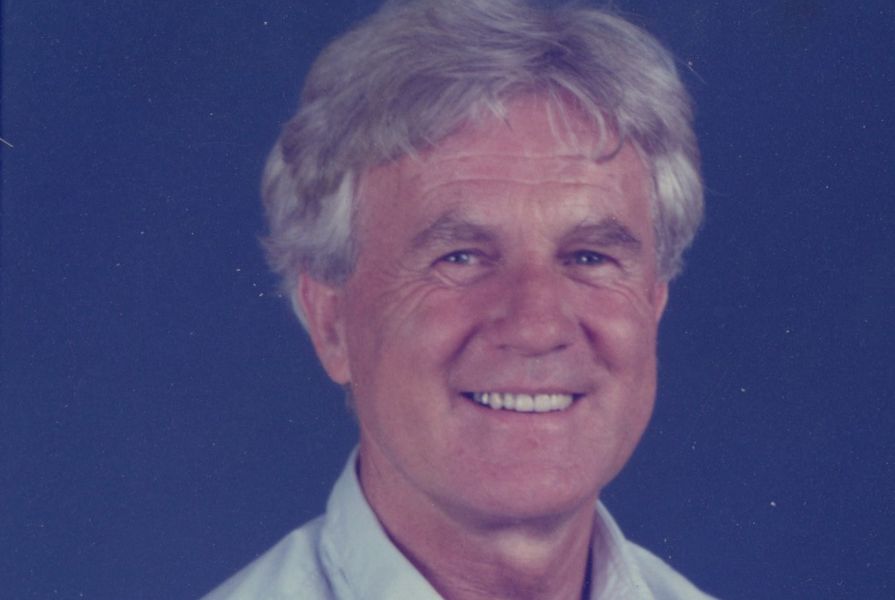

Hugh O’Neill at the drawing board in Ormond College, 1954.

Image: Courtesy O’Neill family

O’Neill’s focus on the social value of architecture was especially important for the hundreds of students who came to Australia from developing nations under post-World War II educational assistance schemes, such as the Colombo Plan. Many of these countries were shaping their cities after a colonial period, and the message of integrating civic and humanitarian issues into administrative and housing construction was not always understood. O’Neill’s broad vision was central to the principles he imparted to many decades of students, and its value can be measured by the devotion they felt for him. It was, however, not only visiting students who felt this way; O’Neill was also respected by several generations of leading Australian architects.

For anyone lucky enough to travel with O’Neill, it was a Pied Piper experience: people were drawn to him and opened their hearts and their homes in a way that is rare for a foreigner. His ability to immerse himself in the customs of the places he visited was inspirational. This ability was integral to his comprehensive interpretation of what architecture should be. For O’Neill, it was never just a theoretical matter. He was always hands-on and his grasp of essential values in building practice was based on his ability to immerse himself into other societies. This was particularly important in Indonesia, where he spent two years (1958–60) as architect and lecturer in what is now the Ministry of Public Works and Housing in Jakarta and Bandung, before two more years (1967–68) based in Yogyakarta. His experiences there strengthened his conviction that architectural practice and theory needed to go beyond the traditional Eurocentric framework and embrace a wider range of cultural achievements. This led to his establishing in 1962 a unique and extremely influential course on the architecture of Asian societies. His pioneering teaching led to the University of Melbourne’s conferring of an honorary doctorate in 2013. In 2014, he was made a life fellow of the Australian Institute of Architects.

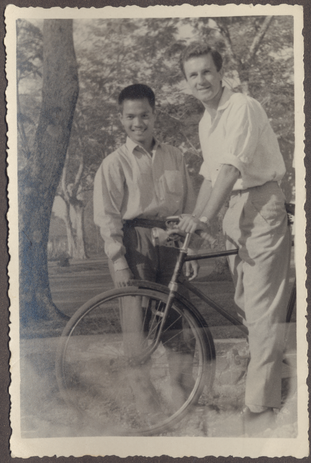

Hugh O’Neill in Bandung, Indonesia, 1958.

Image: Courtesy O’Neill family

While at Deakin, O’Neill was able to explore more deeply the visionary thinking and achievements in the Netherlands Indies between 1913 and 1942 of the Dutch architect and urban planner Thomas Karsten, whose work had inspired him during his times in Indonesia. In company with Professor Joost Coté, O’Neill produced a comprehensive publication that not only established the importance of Karsten’s achievements but also provided a record of his own research. His dedication to teaching had left O’Neill with little time for personal academic pursuits, but his chapter in the influential 1994 publication The Mosque also demonstrates his profound understanding of the unique technical and aesthetic nature of Indonesian architecture.1 Further commitment to the field was enhanced by his time as a visiting fellow in 1988 and 1990 at the Aga Khan Program for Islamic Architecture at Harvard–MIT in Massachusetts.

O’Neill’s love of Indonesia led to his dedicated work for and chairmanship of the Volunteer Graduate Scheme for Indonesia (1961–70), the Australian Indonesian Association of Victoria (1961–75), the Overseas Service Bureau (now AVI) (1972–89) and the Indonesian Arts Society, Victoria (1974–02). He was also instrumental in several exhibitions: Textiles of Indonesia (National Gallery of Victoria, 1976); Musical Instruments of Indonesia (Griffin Gallery, 1983); Masks of Kalimantan (National Gallery of Victoria, 1991); Behind the Shadows: Understanding a Wayang Performance (1996); and AWAS! Recent Art from Indonesia (Australian Centre for Contemporary Art, 1999).

Milton Hall, the grand Victorian terrace house where the O’Neill children grew up (O’Neill and his late wife, Roma, bought the house in 1969 and renovated it) reflected their father’s deep commitment to Indonesian culture. Its characteristic cast-iron lacework and tiled verandah, high ceilings and generous spaces were enhanced by refined batik and woven cloths from Sumba and Bali, and other works. These were integral to the atmosphere, which was often enriched by the gentle strains of gamelan music or of the Bach keyboard works that O’Neill loved. Ripe mangos from the Queen Victoria Market would be heaped on the table, around which generations of friends and family enjoyed long, wide-ranging conversations. O’Neill was a dedicated father to his five children, and a supportive and warm friend to more people from around the world than can possibly be counted. His beaming smile and genuine empathy made all who knew him feel welcome.

In 2013, his country acknowledged O’Neill’s achievements by conferring on him the Order of Australia – a fitting tribute to a remarkable and much-loved man. A few short paragraphs are inadequate to express the richness of a life of exceptional creativity and dedication. For all who knew him, the void he has left cannot be filled.

1. Martin Frishman and Hasan Uddin Khan (eds), The Mosque: History, Architectural Development and Regional Diversity (New York: Thames and Hudson, 1994).