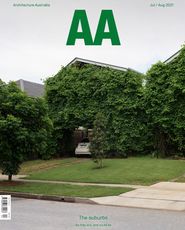

The experimental housing development WGV has been unfolding for six years in the Perth suburb of White Gum Valley. Behind the coastal limestone cliffs of Fremantle and beside a golf course lined with tuart trees sits a series of fascinating experiments with water, energy, landscape and architecture.

A space for housing experimentation and demonstration is of great importance in Australia. In contexts dictated by quantity – where housing factors as a commodity before it factors as a place to live – quality can be scarce. Medium-density demonstrations offer chances to prove and experience the gains in sharing and sustainability that can come from living closer together, as well as giving designers, communities and governments a space to lead the marketplace, setting higher expectations for quality.

In Perth, such a space was created in 2013 by the state’s development agency Landcorp, now Development WA. The liberating ambition was for “innovation through demonstration”: 80 homes and 180 residents across a diversity of housing types on the 2.2-hectare site of a former school.

The WGV experiments set out to recalibrate many of the default settings of contemporary suburban development – detached, environmentally insensitive, yield-driven – in favour of shared, sustainable, high-amenity prototypes.

At SHAC, rent is calculated as a percentage of each resident’s income, enabling artists to remain in Fremantle, where gentrification is driving up house prices.

Image: Edwin Janes

Shared

Emerging at WGV today is an atmosphere of community around a range of collaborations on the major lots. These include a cooperative of affordable, artist-led housing and studio spaces (SHAC); a baugruppe and ownership-based housing initiative (WGV Baugruppe); a private partnership to deliver apartments (Evermore); a design competition for three affordable housing units for Generation Y (Gen Y Demonstration Housing); and a range of single residential lots sold subject to the WGV Design Guidelines.

The first of these projects to break ground was SHAC (Sustainable Housing for Artists and Creatives) – an experiment in sharing for affordability. Through collaborations with Access Housing and With Architecture Studio, this cooperative designed a housing and financial system to keep artists living in a gentrifying Fremantle. Rent for studio spaces and apartments is calculated as a percentage of an artist-resident’s income. Exhibitions, performances and workshops take place across multi-level creative spaces, mezzanines and courtyards between the buildings.

Down the way, the Gen Y Demonstration Housing is built upon another shared spatial idea, folding three units within the skin of a single house. This is an experiment in “density by stealth” – an approach that architect David Barr explored to mingle density into suburbs of detached housing long neglected by local planning controls, finding a material efficiency and affordability in the process.

David Barr Architects won Landcorp’s Gen Y Demonstration Housing project with its proposal for three units that fold into the skin of a single house.

Image: Edwin Janes

Around the corner, the baugruppe will become the next collaborative development at WGV. Led by a group of housing owners, this is a design-driven model with a target cost saving of 15 percent on market value. Here, architect Spaceagency deftly interlocks the baugruppe dwellings around their own generous courtyard, enabling substantial flexibility as participants join and shape their own designs.

Testing new ground, the shared endeavours at WGV have not been without their challenges. The collaborations have relied heavily on the passion of the individuals, collectives and designers leading them. This is the promise of experimentation: to create models of the future that can be replicated with greater ease.

There was not a radical redrawing of the conventional precinct structure to build in sharing, and it is the selection of innovative collaborators, rather than the site planning, that facilitates the shared spaces at WGV. This lot-by-lot approach to sharing means that substantial shared civic and landscape spaces have not found their way to the heart of the precinct. Instead, the open spaces – including an existing community hall, a barbecue area and a drainage basin – wrap around the edges of the site. In some places, such as SHAC, the housing lots blur with this perimeter of open space, but in many others, such as at Evermore, there are barriers to connection through level changes and fences.

Sustainable

Sharing extends to the water and energy infrastructure at WGV, which has been a “living laboratory” for the Cooperative Research Centre for Low Carbon Living in conjunction with Curtin University. The four-year research program involved university students and industry working together to test ideas and share learning. Some of the most important impacts of WGV have been in education – school and university students are frequently visiting the site to learn about the importance of sustainability in our suburbs.

Many of the experiments with water have been designed by Josh Byrne and Associates. The transformation of a functioning but derelict drainage basin into a thriving park is a victory for water diplomacy. There are several thousand of these basins, or “sumps,” in the Perth suburbs. They direct stormwater runoff into sandy depressions that percolate to deep aquifers – but they are invariably overgrown and fenced off by the infrastructure authorities. At WGV, infrastructure is converted into parkland, with trees, rushes and understorey brimming with birdlife. The basin park retains its utility as a sump: water irrigates the vegetation, and vegetation treats the water on the way to the aquifer. In this way, WGV serves as a vital prototype for landscape potential across Perth’s basins.

The conversion of a drainage basin created useable public open space and increased the tree canopy while retaining the sump’s utility.

Image: Edwin Janes

On site is a community bore, drawing up water to irrigate courtyards, green balconies, vegetable gardens and fruit trees. In Josh Byrne’s words, “The aquifer becomes our tank,” sharing water through Perth’s long, rainless summers and substantially reducing scheme water use. A carefully considered water balance underpins the system so that stormwater infiltration exceeds groundwater abstraction. This is a positive move in Perth, where around 200,000 unmonitored garden bores contribute to the depletion of aquifers. Coupled with rainwater tanks and waterwise hardware, each WGV resident’s water use becomes a fraction of the average Perth resident. This massively reduces carbon footprints in a city where around half of scheme water comes from emissions-intensive Indian Ocean desalination.

WGV has also pioneered energy sharing in an Australian context. The Gen Y Demonstration Housing, funded and built by Development WA, was the testing ground for the Power Ledger system devised by researcher-turned-entrepreneur Jemma Green. Power Ledger monitors and moves energy in a blockchain between solar photovoltaics, batteries, the grid and the dwellings, billing each separately. These peer-to-peer trading systems have become widely adopted models of energy governance as Power Ledger has gone to market. The Evermore apartments, designed by Harris Jenkins Architects and built by Yolk Property Group, scale these energy approaches to 24 apartments to form a microgrid. Residents sell their solar excess to their neighbours when demand calls for it, before the system will sell to the grid. These energy innovations are featuring prominently in Evermore’s marketing, suggesting that low running costs might become the marketable metric in suburbs of the future.

A “deep” plan?

Questions of “deep” and “surface” interpretations of sustainability inevitably emerge from the WGV experiments. In the context of a climate emergency, sustainability needs to include all the “gadgets”: solar panels, integrated water systems, innovative building materials. But it also needs to go deeper and wider than this, to consider how the planning of our suburbs can save and strengthen existing blue–green systems: bushland, parks, tree canopy, verges, waterways, urban drainage and even sumps. In its truest sense, sustainability is about these whole systems working together as blue–green infrastructures. In Perth, these systems are within one of 36 global biodiversity hotspots – regions of extreme value to human and ecological health that are threatened by human impacts. How can we listen to these existing contexts, rather than simply erasing them, only to create new ones in their place?

WGV’s converted sump serves as a vital prototype for the thousands of derelict sumps across Perth.

Image: Robert Frith

Not everything at WGV has met these sustainability benchmarks. Sadly, the conventional lot layout and level changes uprooted more than 100 mature trees (mostly eucalyptus and Western Australian peppermints), disrupting the ground conditions and topography of the old, leafy Kim Beazley School. Sites were filled and benched, a brutal approach that is common across urban development in Perth. Although the new landscaping targeted a tree canopy to make up for the loss, this speaks to an all-too-familiar problem across infill development in Australian cities. At a systems scale, these impacts are critical – according to the Western Australian government, 644 hectares of tree canopy was lost on inner suburban private lots in Perth between 2009 and 2018. The 23 single residential lots at WGV resulted in mixed outcomes, highlighting the limits of lot-by-lot thinking. Half of these lots run north–south, with their north ends pointing onto streets rather than gardens. And although every lot provides some design opportunity for solar access, the east– west lots are so narrow that solar access is often difficult when dwellings are built to two storeys. Knowledge and iterations have arisen from these experiments: new demonstrations by Development WA take tree retention more seriously, and canopy incentives will become part of Design WA, the state’s proposed housing codes.

WGV has provided a canvas for communities, researchers and designers to make, share and reflect on new prototypes. The government has a vital role in seeding these prototypes that help to lead the marketplace and in instigating environmental planning to support them. As the WGV experiments start to go beyond lot-by-lot thinking and to scale up, they move from informing the single patch to the suburban matrix (to invoke concepts of landscape ecologist Richard T. T. Forman). There is urgency and opportunity here for designers to lead and arrange suburbia in new ways – with ecology, hydrology and sociality front of mind. WGV constitutes many outcomes – some best-practice, some standard – and a lot of learning and discovery in an invaluable testing ground.

— Daniel Jan Martin is a freelance designer and environmental planner based in Perth. He teaches and researches in architecture and landscape architecture at the UWA School of Design.

Credits

- Project

- Gen Y Demonstration Housing

- Architect

- David Barr Architect

Fremantle, WA, Australia

- Project Team

- David Barr, Stephen Hicks, Tom Smith

- Consultants

-

Builder

Perth Builders

Electrical Balance Services Group, Best Consultants

Engineer Instruct Consulting Engineers

Hydraulics Ionic Design

Landscaping Josh Byrne and Associates

Life cycle assessment eTool

- Site Details

-

Location

Perth,

WA,

Australia

Site type Suburban

Site area 250 m2

Building area 145 m2

- Project Details

-

Status

Built

Design, documentation 9 months

Construction 9 months

Category Residential

Type New houses

Credits

- Project

- SHAC (Sustainable Housing for Artists and Creatives)

- Architect

- With Architecture Studio

WA, Australia

- Project Team

- Geoff Warn, Daniel Aisenson, Jane Wetherall, Christian Nichols, Raymond Loo;

- Consultants

-

Acoustics

Herring Storer Acoustics

Building surveyor, safety in design and fire engineer JMG Building Surveyors

Contractor Jaxon

Hydraulic, electrical, communications and mechanical engineer Wood and Grieve Engineers

Precinct civil engineer Tabec

Precinct landscaping Josh Byrne and Associates

Section J consultant ESD Consulting

Structural engineer and project civil engineer Airey Taylor Consulting

- Aboriginal Nation

- Built on the land of the Whadjuk people of the Noongar nation

- Site Details

-

Location

Perth,

WA,

Australia

Site area 1350 m2

Building area 1050 m2

- Project Details

-

Status

Built

Completion date 2016

Category Residential

Credits

- Project

- WGV

- Client

-

Landcorp/Development WA

- Consultants

-

Architect

Coda Studio/The Fulcrum Agency, Donaldson and Warn/With Architecture Studio, David Barr Architects, Harris Jenkins Architects, Spaceagency Architects, UWA School of Design/Geoffrey London

Civil engineer Tabec

Landscape architect Josh Byrne and Associates

Researchers Curtin University/Cooperative Research Centre for Low Carbon Living

Town planning Urbis

- Aboriginal Nation

- Built on the land of the Whadjuk people of the Noongar nation

- Site Details

-

Location

Perth,

WA,

Australia

- Project Details

-

Status

Built

Category Residential

Source

Project

Published online: 24 Aug 2021

Words:

Daniel Jan Martin

Images:

Edwin Janes,

Nearmap,

Robert Frith

Issue

Architecture Australia, July 2021