“… but in the end, unless there are attitudes of respect and a becoming humility when you are engaging with communities, so that their voices are genuinely heard, I think the game is over.”

Fred Chaney, Which Way? Directions in Indigenous Housing, 2007

“We have to remember that if you want things to work, you have to involve the people who are affected. Otherwise it is destined to fail, and when it does we all suffer.”

William Tilmouth, Which Way? Directions in Indigenous Housing, 2007.

Architecture has traditionally operated at the juncture of patronage and political economy, translating historically located desires into images and built form. Never more so than where architecture and Indigenous housing are concerned – here the task of translating is layered, not only with the policies of the day, but also with a culture and language foreign to the non-Indigenous architect, who carries their own assumptions and priorities.

What other architectural brief for a single family house has, at its core, cultural practice, health outcomes and community employment? What other architectural program has such a tangled arrangement of federal, state and local government structures? And in a country where owning a home is a dream for many, what sort of uncanny dream conjures a built form that, for traditional Indigenous Australians, has little cultural value and yet such dire effects?

It has been suggested that Western-style housing may indeed be another means of colonizing Indigenous Australians, of forced assimilation, of controlling mobility and cultural expression. Housing in this analysis is a fixed physical entity that fails to respond to deep-seated cultural requirements for moving within and around country. Yet housing is not mute. There are undeniable and challenging problems with Indigenous health and standards of living, which poor housing exacerbates and which better housing can alleviate.

In light of the federal government’s emergency intervention into the Northern Territory and the promise of many hundreds of millions of dollars in housing funds, it is worth reflecting on the experience of a group of architects who have been engaged with housing for Indigenous Australians for more than thirty years.

Tangentyere Design is an Aboriginal-owned architectural practice based in Central Australia. It began in the late 1970s as a division of Tangentyere Council, an Aboriginal organization established to represent the interests of Indigenous people in their quest for land tenure, housing, infrastructure and basic standards of living in the town camps of Alice Springs. When it was first created, the design division of Tangentyere Council provided architectural advice and designs for housing and community facilities as well as masterplans for community layouts in the town camps. Over the decades, Tangentyere Design – as it has since become known – has provided architectural services to Indigenous people living in Alice Springs and in other, more remote central desert areas. It has won numerous design awards, helped to build a range of housing and community buildings throughout the Northern Territory and, above all, it has remained committed to engaging with Aboriginal people in the creation of a healthier built environment.

The theory

The breadth and complexity of Indigenous housing research is well documented in collections such as Take 2: Housing Design in Indigenous Australia and the more recent Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute survey of literature on Indigenous housing. It is useful to locate Tangentyere Design within this context.

It is now accepted within the architectural profession that three paradigms broadly characterize Indigenous housing design. The Cultural Design paradigm starts from the premise that appropriate design will only come from observing the culturally distinct domiciliary behaviours of Aboriginal people, and addressing the range of customary family units and behaviour patterns with appropriate design responses. The Environmental Health model is a technological approach and is exemplified by the work of Healthabitat and the Fixing Houses for Better Health program, out of which has come the National Indigenous Housing Guide and the nine healthy living practices. The housing-as-process model is a wider framework that includes consideration of culture and technology, but is also focused on community aspirations and capacity, and assumes a broad consultative approach to housing provision. Other practitioners have recently begun to frame a multidisciplinary or hybrid approach called the Design Framework, which attempts to synthesize the complexities of each of the paradigms into a comprehensive methodological approach to housing design and delivery.

Tangentyere Design’s work has not been consciously allied with one or other of these paradigms. Its practice can be broadly described within each, and indeed its work has contributed much to formulating the modes of understanding architectural work with Aboriginal clients.

The practice

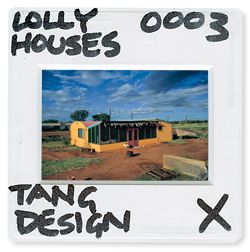

One of the Lolly Houses for the Yuendumu Old People’s Program in 2000.

Tangentyere Design has had an exemplary range of architects pass through its doors over the decades. Many have moved on to form successful architectural practices of their own and continue to work with Aboriginal people throughout Australia. Each has contributed to the shape of the practice, to establishing its principles and to a respected body of work.

Paul Memmott’s thorough 1989 review of Tangentyere Council’s early years identifies a number of distinct architectural periods defined by the senior architects of the time. The first of these architects began working closely with town camp residents to develop a new and culturally appropriate architectural language in the late 1970s, when the establishment of permanent lease arrangements meant that town campers were finally able to secure entitlements to basic housing and infrastructure.

By observing camp layouts, humpy construction, familial relationships, externally oriented living habits and other culturally distinct ways, these architects developed two-, three- and four-bedroom house types that could be easily modified to suit particular requirements. The houses were simply constructed of concrete slabs, masonry walls and metal roofs. Toilet cores were located at the perimeter, kitchen and living areas combined, and the number of bedrooms could be varied. External verandahs and windbreaks were added to provide protected outdoor living areas.

In the mid-1980s, housing design at Tangentyere was characterized by more formalized pitched roofs with hips and gables, extensive verandah spaces and the integration of landscaping as a means of controlling summer sun and winter winds. For Tangentyere the critical focus of house design was not a matter of the one-size-fits-all approach that characterizes much of Indigenous housing today. Rather, Tangentyere Design emphasized close consultation with the residents to determine design strategies.

In the 1990s and early 2000s housing in the Northern Territory was delivered under a variety of policies. During this time Tangentyere Design contributed to a range of programs funded by NAHS (National Aboriginal Health Strategy) and IHANT (Indigenous Housing Authority of the Northern Territory), including Tangentyere NAHS, Mutitjulu NAHS, Papunya NAHS and other new housing and refurbishment projects throughout the Territory.

At this time, Tangentyere Design undertook extensive surveys of town camp housing in an effort to improve basic health hardware standards and specifications. As well as exploring improved fittings and fixtures, Tangentyere continued its longstanding interest in integrating landscape with the fundamentals of house design. Measures included earth mounding to protect trees and provide windbreaks, sand areas for fire pits, and temporary reticulated irrigation to assist in plant establishment.

Perhaps the most challenging and rewarding effort of this time was Tangentyere’s introduction to the standard IHANT houses of an attached “granny flat”, with a wheelchair-accessible bedroom and bathroom to provide independent living areas for older residents. It was also instrumental in developing sturdy kitchen pantries and bedroom robes made of steel framing and perforated metal shelving, components that are now standard in Indigenous housing. Tangentyere, through discussions with Aboriginal clients, also introduced a palette of bright and varied colours to many of its projects. The most notable was the award-winning “Lolly Houses” for the Yuendumu Old People’s Program in 2000.

While Tangentyere’s house designs have evolved over the years and funding arrangements have taken a perplexing number of forms, the one constant in its approach has been engagement: listening to Aboriginal clients and trying to understand individual needs and aspirations.

The present

In addition to its wide range of work in remote communities throughout the Northern Territory – including art centres, child care centres, safe houses, community kitchens and other facilities – Tangentyere Design is currently engaged with Tangentyere Council’s housing and construction divisions in a major housing refurbishment program on the Alice Springs town camps.

The practice continues to look to its past and the principles on which it was founded, and engaging with Aboriginal people remains an essential component of the upgrades project. Residents are asked to draw on their own house stories and consider their priorities. Which rooms are too small, how often the toilets back up, whether there are elderly residents with special needs, what areas of the yard are used and at what time of day and year, how many visitors are received, and what outdoor areas are used for sleeping, cooking and playing.

Tangentyere Design’s work has had many successes and we continue to learn from our shortcomings. Landscaping, for example, is often difficult to maintain, leaving walls exposed to summer sun. Wet area drains have failed where there are insufficient falls to floor wastes or poorly installed drainage pipes. Failures in house technology can be attributed to design and construction, but also to the stresses of increasing numbers of occupants in houses that are more appropriate for smaller family groups. And these stresses will continue to mount as Aboriginal people move into the town centres in response to changing government policies and for access to services not available in remote areas.

The future

There is a housing crisis in Australia’s Indigenous communities. Too few houses, too many needing repair. No-one denies this. The reasons for the crisis are tied to history, to politics, to an array of ever-changing Indigenous policies that have ranged from assimilation to self-determination to intervention.

Adding to the bewildering tangle of decisions, construction and transportation costs in remote areas continue to rise. The availability of skilled labour is low. Government funding agents continue to scramble to find cheaper and faster ways of delivering housing. And the industry has obliged with various transportable and semi-transportable housing types. Everyone has an answer to housing Indigenous Australians. But there is no clear evidence of engagement, nor an understanding of what the clients want. It is doubtful that cheaper and faster will “solve” the housing crisis when engagement is not part of the equation.

While the politics of the day demand so-called “normalization” of town camps and the transformation of culturally distinct Aboriginal settlements into new suburbs, the question of engagement remains. Where federal and territory funding provides for new and refurbished “innovative” housing, we have to ask whether flat packs and transportable boxes will address the problem or indeed become the problem.

Tangentyere Design does not have the answers to designing Indigenous housing, but thirty years of working on the ground with Aboriginal people has shown that decision-making about the form and functions of a house must include the occupants if it is to begin to be useful and at all sustainable.

The conceit of architects and housing advocates is that by solving the housing problem we can also solve the problems of poor health and high mortality, substance abuse and domestic violence, unemployment and literacy. But experience tells us that socioeconomic disadvantage – whether it occurs in black or white Australia – will not be solved with a better house alone. The basics remain: genuine client and community engagement from design to construction to occupancy, adequate and reliable financial resources, commitment to ethical procurement strategies, technical knowledge of materials and methods of construction, detailed post-occupancy evaluations.

Architects cannot promise social progress, but listening is a substantial beginning.

Andrew Broffman is a senior architect at Tangentyere Design.

References

F. Coglin, Aboriginal Town Camps and Tangentyere Council: The Battle for Self-determination in Alice Springs, MA Thesis, La Trobe University, 1991.

J. Fien, E. Charlesworth, V. Lee, D. Morris, D. Baker and T. Grice, Flexible Guidelines for the Design of Remote Indigenous Community Housing, (Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute, 2007.)

J. Fien, E. Charlesworth, V. Lee, D. Morris, D. Baker and T. Grice, Towards a Design Framework for Remote Indigenous Housing, (Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute, 2008.)

M. Heppell and J. Wigley, Black Out in Alice: A history of the establishment and development of town camps in Alice Springs, (Monograph 26, Development Studies Centre, Australian National University, 1981).

S. Long, P. Memmott and T. Seelig, An Audit and Review of Australian Indigenous Housing Research, (Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute, 2007).

P. Memmott, “The Development of Aboriginal Housing Standards in Central Australia: The Case Study of Tangentyere Council”, in B. Judd and P. Bycroft (eds.), Evaluating Housing Standards and Performance (Royal Australian Institute of Architects, 1989).

P. Memmott, Gunyah Goondie and Wurley: The Aboriginal architecture of Australia (University of Queensland Press, 2007).

Memmott, P. (ed.), Take2: Housing Design in Indigenous Australia (Royal Australian Institute of Architects, 2003).

P. Morel and H. Ross, Housing Design Assessment for Bush Communities, (Tangentyere Council, NT Department of Lands, Housing and Local Government, 1993).

S. Prout, The Entangled Relationship Between Indigenous Spatiality and Government Service Delivery, CAEPR Working Paper no. 41 (Australian National University, 2008).

A. Szava, M. Moran, B. Walker and G. West, The Cost of Housing in Remote Indigenous Communities: Views from the Northern Territory Construction Industry (Centre for Appropriate Technology, 2007.)